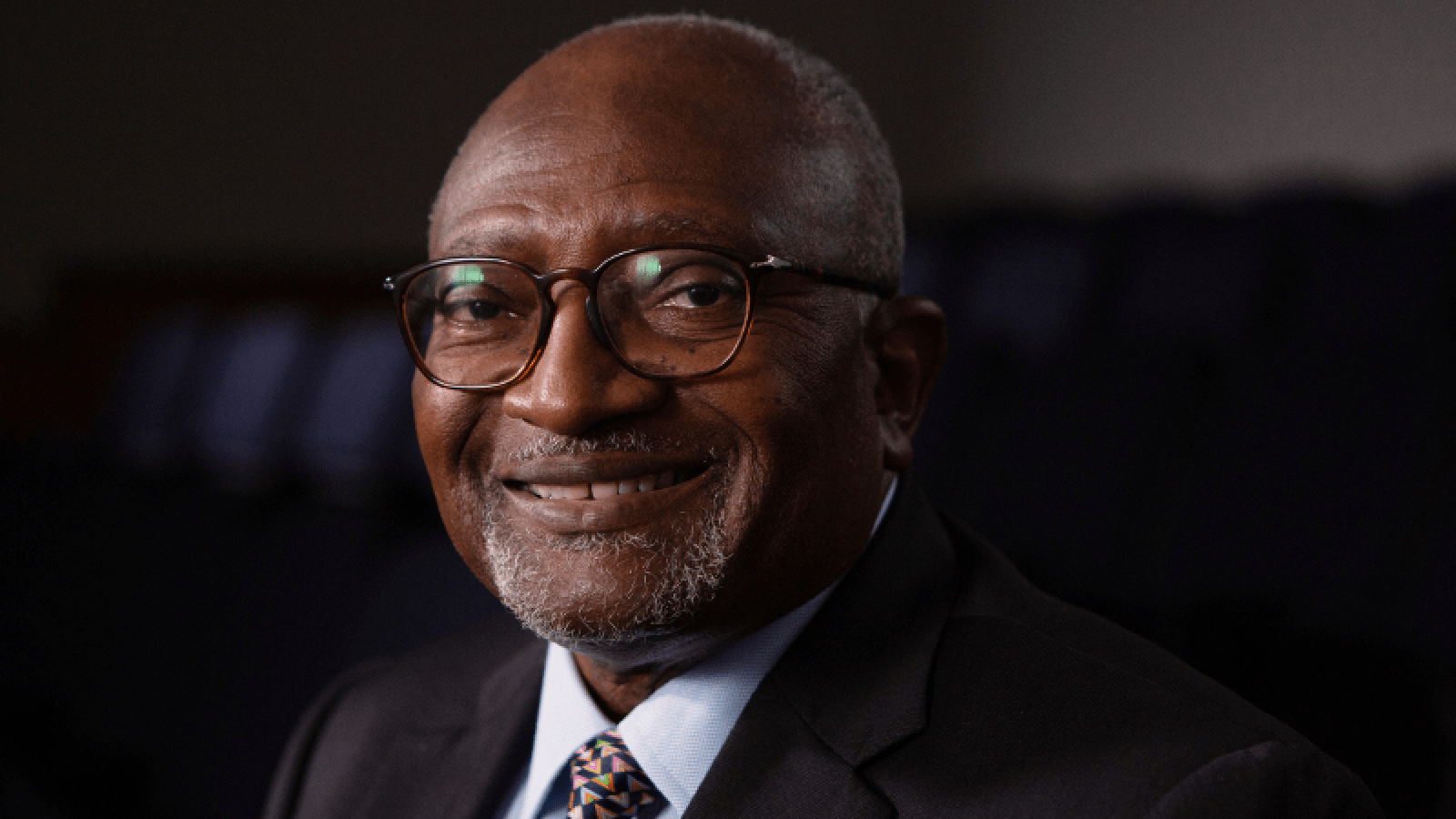

Robert Bullard is often called the “father of environmental justice” for his more than four decades of pioneering work integrating human and civil rights with environmentalism. The author of 18 books, Bullard is a distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy and director of the Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice at Texas Southern University. We spoke recently at the Ten Across 2023 Houston Summit after a panel discussion highlighting climate resilience — the ability of people and communities to prepare for, adapt to, and recover from hazards caused by a changing climate.

This interview has been lightly edited.

Yale Climate Connections: Dr. Bullard, earlier, a speaker mentioned that climate change is forcing officials to pay attention to problems that once primarily affected Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities — things like flooding, for example. But if the government doesn’t change how it treats marginalized communities, won’t it just replicate the same racist patterns of the past when struggling with issues of climate resilience?

Robert Bullard: Oh, yes. We need to build the justice lens into the process, otherwise, we will reproduce that old paradigm of letting power, and planners who are privileged, make the plans and somehow not think that the equity part must be considered. Or it may be considered, but it’ll be a footnote.

Our environmental justice framework speaks to the issue that those who are most impacted must be in the room when decisions are being made and plans are being drawn up — and not only [be] in the room. They must have a significant say as to what kinds of projects, initiatives, and resources are advanced, and how they get applied.

That’s the justice and equity frame that we have been pushing for the last four decades. And it’s only recently that we’ve made tremendous breakthroughs when it comes to getting that equity lens applied at the federal level. We desperately need federal oversight and the federal government pushing out this framework because we have 50 states, but not all 50 are created equal.

YCC: Do any particular problems or solutions come to mind when you think about climate change in the Southwest?

Bullard: Yes, I think the Southwest has some unique issues because of demographics and because of the legacy of how the state governments have dealt with Indigenous people. Not just the federal government, but also in terms of state-to-sovereign nations. We have to look at the extent to which resources have somehow not flowed to those communities and how decisions are oftentimes made for communities, not with them.

When we talk about issues of resources, we talk about extraction, or mining, and also about water issues. And in cities, we talk about the places that are considered nature-deprived and urban heat islands. These areas also have more than their fair share of pollution.

Read: Climate justice organization tackles urban heat and more in Arizona’s Maricopa county

When we apply that equity lens in the states that you’re talking about, you get the same kinds of results in terms of low-income communities, people of color communities, Indigenous communities, somehow getting more than their fair share of the negative externalities [for example, higher rates of childhood asthma in neighborhoods close to coal-fired power plants].

So our climate justice framework has an equity lens that’s to be applied in terms of how policies and decisions get made, how resources get allocated, and how we measure success. That equity lens can mean the difference between life and death to a community.

YCC: One climate change issue in the Southwest is that we don’t have “heat waves” in the sense that many northern areas do. Our summers are always dangerously hot and it’s disproportionately people of color who are hit hardest. Our temperatures are rising, but if you don’t live here, you’re less apt to think about the difference between 112 degrees and 122 degrees.

Bullard: True. A lot of people don’t know that heat is the No. 1 killer when it comes to severe weather events. Not drowning, not wind damage. Heat. And when you layer on climate impacts in terms of the increasing temperatures and look at the environmental and health disparities that existed before this extra heat, climate change becomes a multiplier.

For example, low-income families may not have access to air conditioning because of economic disparities. And even if they do, that extra time running that AC means more disruption of household budgets. If it’s an elderly household on a fixed income, then we’re talking about tremendous impacts. An elderly person may not want to turn on the AC because their Social Security might be eaten up just by that monthly electric bill. So when we talk about climate impacts, in terms of heat, we also have to talk about economic impacts, health impacts, and the social impacts of disruption of family life.

We also have to think in terms of outdoor workers who are 35 times more likely to die from exposure to extreme heat than the general population. Now, outdoor workers are disproportionately people of color. So we can talk about the loss of wages for those jobs because if you don’t work, you don’t get paid. You’re also talking about health as well as the economic disruption that disproportionately impacts people of color and working-class folks.

Oh, there’s another thing: heat and schools. Money is allocated to most schools based on property taxes. If you look at poor school districts, oftentimes with lower housing values, those districts are not able to have the kinds of infrastructure, like air conditioning, in their schools. So when it gets too hot to learn, the pupils who attend those schools will suffer — in many cases, disproportionately students of color. That’s why we need to have infrastructure dollars flowing from the federal government into those school districts to address those infrastructure disparities so that our children don’t fall further behind. Those are the equity impacts in terms of workers, in terms of households, and in terms of schools and children.

YCC: In many larger Southwestern cities, we have wealthy neighborhoods where you’ll find shade trees everywhere. That isn’t true of poorer neighborhoods.

Bullard: Seventy-four percent of people of color live in what’s called “nature-deprived areas,” versus 23% of whites. So access to nature oftentimes tracks with income and race. And it is no accident that rich Americans have 50% more green space and trees than poor Americans. And so having trees and green canopy and access to parks or green space — oftentimes, it’s not dictated by just randomness. In many cases, you can track it all the way back a hundred years in terms of how the city was laid out, in terms of planning the infrastructure.

Read: The link between racist housing policies of the past and the climate risks of today

Tree canopy is part of infrastructure. Trees do more than just provide shade. They can foster livability. So when your areas are just barren of green space, parks, green canopy, you’re talking about not only the impact that’s having in terms of it’s hotter, but also you don’t have those beneficial and nurturing effects of nature.

These are justice issues that we have to address and build into our planning in terms of how we’re going to be dealing with climate resilience and sustainability. So we need to talk about all these for the future.

But we also have to understand that the future is now. Climate change is happening right now, and the communities that have contributed least to the problem are the same communities that are feeling the hurt first, worst, and longest. So the communities that don’t have the green canopy? They can’t wait 20 years. They’re suffering right now.