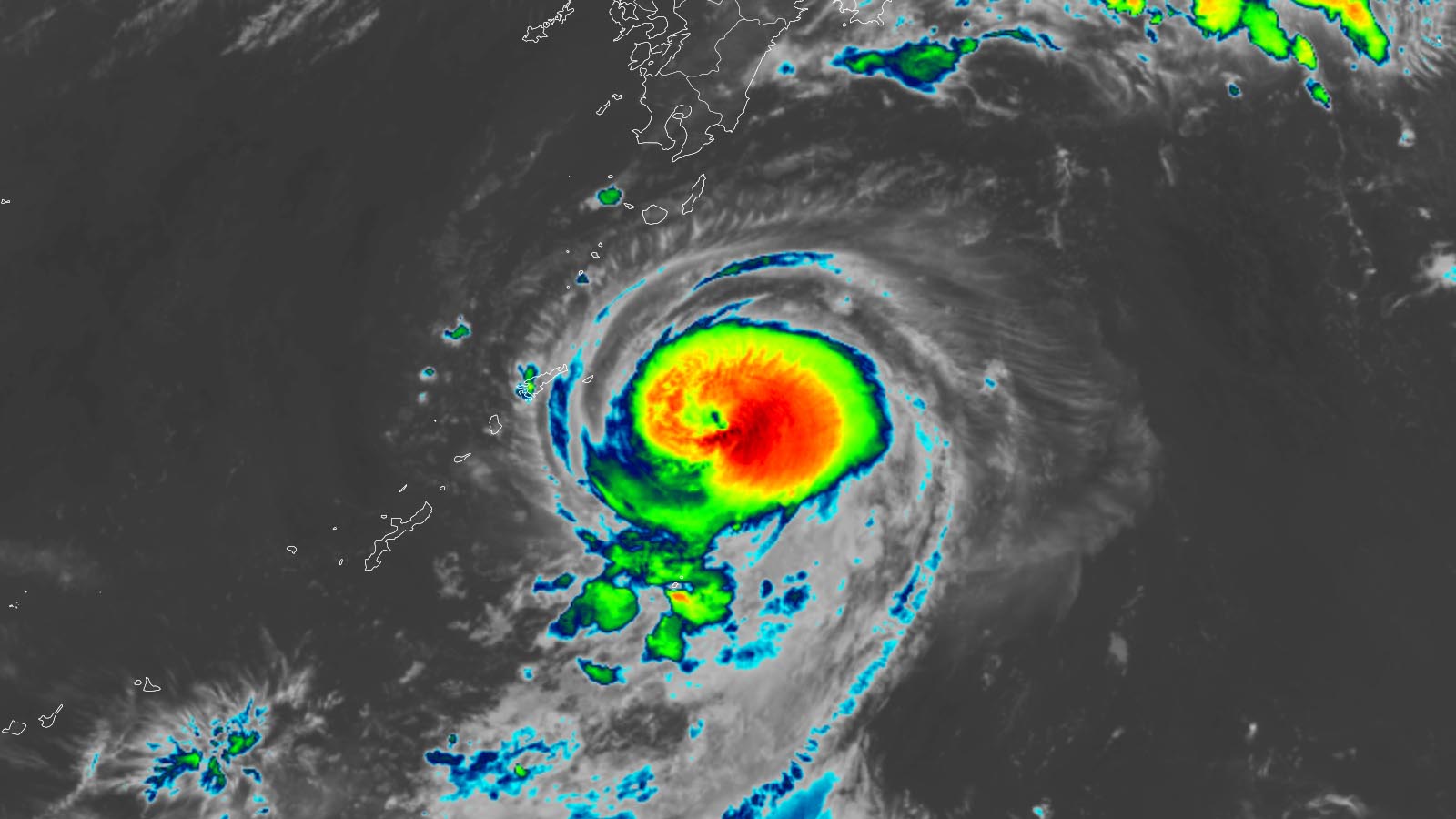

Typhoon Shanshan is intensifying over unusually warm waters of 30-31 degrees Celsius (86-88°F) southeast of Japan. At 11 a.m. EDT Monday, Shanshan was a Category 2 storm with 105 mph winds with a central pressure of 958 mb and was located 267 miles east-northeast of Okinawa, headed west-northwest at 9 mph, according to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center.

Satellite loops showed that Shanshan had a solid area of heavy thunderstorms surrounding a prominent eye but moderate wind shear of 15-20 knots was slowing development. Shanshan’s peak intensity is predicted to occur Tuesday afternoon and evening (U.S. EDT) when the Joint Typhoon Warning Center predicts the typhoon will be moving through Japan’s Ryukyu Islands as a high-end Category 3 storm with 125 mph winds (one-minute average). The Japan Meteorological Agency predicts that Shanshan’s peak will come Wednesday morning (U.S. EDT), when the storm will have 10-minute sustained winds of 100 mph and a central pressure of 950 mb. Both agencies predict that less favorable upper-level winds will cause Shanshan to weaken before making landfall in Kyushu Thursday.

Shanshan has been a very difficult storm to predict; the 11 a.m. EDT Monday forecast by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center shows a Cat 1 landfall occurring nearly two days delayed and over 400 miles to the southwest of the landfall forecast from Friday, which called for a Cat 4 landfall. The models continue to struggle with the track and intensity forecasts for Shanshan, and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center gave only medium confidence to their forecast.

Major landfalling typhoons are uncommon in Japan

According to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center, since accurate record-keeping began in 1945, only 16 Category 3 or stronger typhoons have made landfall on one of Japan’s four main islands (Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku, and Hokkaido). The most recent landfalling major typhoon was Malakas of 2016, which hit southern Kyushu Island, killing one person and causing over $300 million in damage. Two Category 4 typhoons have hit Japan: Shirley of 1965 made landfall in Honshu with 150 mph winds, causing 60 deaths; Yancy of 1993 made landfall on Kyushu with 130 mph winds, killing 48 and doing $3 billion in damage. Japan has experienced only one Category 5 typhoon landfall — the infamous Typhoon Vera of 1959, Japan’s deadliest typhoon, with 5,098 deaths.

Costliest Japanese typhoons

Shanshan has the potential to be one of the costliest typhoons on record for Japan if it hits a sufficiently heavily populated area at Category 2 strength or higher. According to inflation-adjusted damage estimates from EM-DAT, these are the costliest Japanese typhoons since 1945:

Mireille, 1991, $22 billion

Hagibis, 2019, $20 billion

Jebi, 2018, $15 billion

Songda, 2004, $15 billion

Faxai, 2019, $11 billion

Flo, 1990, $9 billion

Bart, 1999, $9 billion

Sarah, 1986, $6 billion

Vera, 1959, $6 billion (5,098 deaths)

Ida (Makurazaki), $7 billion, 1945 (3,746 deaths)

This list does not include the $12 billion flood disaster in southern Japan in July 2018, which was caused by the presence of a stationary seasonal frontal boundary enhanced by remnant moisture from Typhoon Prapiroon.

Looking back at Japan’s only Cat 5 landfall on record: Typhoon Vera (1959)

On September 26, 1959, Typhoon Vera made landfall as a Category 5 storm with 160 mph winds on the coast of Japan’s Honshu Island, bringing a catastrophic storm surge of 3.55 meters (11.6 feet) to Nagoya. The storm surge inflicted heavy losses on the city, turning the harbor into a “sea of dead,” while enormous waves killed 300 people and destroyed 250 homes in the town of Handa, southeast of Nagoya. Vera killed 5,089 people, injured 38,000, left 1.6 million homeless, and inflicted $6 billion in damage (2023 USD).

In the wake of Vera, dikes and sea walls were built to protect Nagoya against the storm surge equivalent to that caused by Typhoon Vera, entrances to subway stations were protected from flooding by tide protection doors, and many other flood defense measures were taken. As a result, Nagoya is much less vulnerable to the storm surge from a Category 5 storm. A 2010 storm surge study by Sousounis and Kafali found that “with minor exceptions the current levee system is sufficient to withstand a repeat of Typhoon Vera.”

However, global warming combined with sea level rise is increasing the risk of typhoons even stronger than Vera for Japan. Sea level rise since 1959 has been about 20 centimeters (eight inches) in Nagoya, making it easier for a storm surge to overtop sea walls. A 2020 study found that future global warming could be expected to bring Nagoya a “maximum potential typhoon” with sustained 10-minute average winds of 60 m/s (134 mph) and a central pressure of 885 mb. If the storm hit at high tide, a storm surge two meters (6.6 feet) higher than Vera’s would likely result, overwhelming Nagoya’s flood defenses, bringing destructive currents traveling down narrow city streets between buildings with speeds in excess of 10 m/s (23 mph).

If a repeat of Vera were to occur today, wind damage would be much greater, because of the increase in population and wealth. The Nagoya metro area had a population of 4 million in 1959 and now has a population of 9.6 million. A 2009 study by RMS found wind damage from a repeat of Super Typhoon Vera would cost $20-$26 billion (2024 USD). The storm surge would likely cause additional billions in damage, largely in areas not located behind the city’s flood walls.

Hurricane Hone drenches Hawaii’s Big Island

Hurricane Hone made its closest approach to Hawaii’s Big Island on Sunday morning, passing about 50 miles south of South Point. At that time, the hurricane had sustained winds of 85 mph and a central pressure of 988 mb. The strongest winds on the Big Island appear to have been those driven by localized downslope mountain-wave effects as easterly winds careened down west-facing slopes – the same mechanism that stoked the catastrophic fires in Maui last year. Hone brought torrential rains to the east side of the island, with 36-hour accumulations of up to 22.38 inches. The hurricane knocked out power to over 20,000 customers, but no major damage was reported.

Right behind Hone is Hurricane Gilma, which peaked as a Category 4 storm with 130 mph winds on Sunday morning. Gilma is expected to weaken to a remnant low with 35 mph winds by Friday when it is predicted to pass just north of Hawaii’s island of Maui. And behind Gilma comes Tropical Storm Hector, which is expected to weaken to a tropical disturbance before reaching the Hawaiian Islands this weekend.

We help millions of people understand climate change and what to do about it. Help us reach even more people like you.

Source link