The Atlantic won’t be ginning up any tropical cyclones for at least a few days – an unusual but not unprecedented late-August hiatus that we’ll discuss in a future post – but the Pacific will be bubbling with tropical storms, hurricanes, and a typhoon over the next week.

The most serious concern by far is Typhoon Shanshan, predicted to barrel north-northwest while intensifying this weekend. Shanshan is likely to accelerate head-on into central Japan on Tuesday local time as the equivalent of a Category 4 hurricane with 140 mph winds, according to the 11 a.m. EDT Friday advisory from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center. If Shanshan makes landfall at that intensity, it would be the third-strongest typhoon to hit one of Japan’s four main islands since record-keeping began in 1945.

At 11 a.m. EDT Friday, Shanshan was upgraded to a Category 1 typhoon with 75 mph with a central pressure of 983 mb and was located 1,150 miles south-southeast of Tokyo, headed north-northeast at 5 mph. Typical for developing low-latitude systems in the Northwest Pacific, satellite loops showed that Shanshan already had an expansive shield of showers and thunderstorms, with strong upper-level outflow evident on satellite. Dry air on the west side and moderate wind shear of 15-20 knots was slowing development.

The specifics on landfall timing, location, and intensity have yet to be ironed out, but the models have been in broad agreement that Shanshan will arc gently toward the northwest this weekend, then pick up speed while angling north-northeast and racing across the middle of Japan’s largest and most populous island, Honshu, on Tuesday local time. Conditions will be highly favorable for Shanshan to rapidly intensify, as sea surface temperatures along its path will be unusually warm for late August, hovering between 29 and 30 degrees Celsius (84-86 degrees Fahrenheit).

In its final 24 hours before landfall, Shanshan is projected to experience low wind shear while passing over 30°C/86°F waters – some 2°C/4°F warmer than average – together with a pocket of deep oceanic warmth (75-100 kilojoules per square centimeter), which will help boost the odds of a burst of rapid intensification. Such quick strengthening just prior to landfall is a hallmark of many recent tropical cyclones, consistent with human-warmed climate change raising ocean temperatures. Multiple studies have found apparent trends toward more frequent rapid intensification, including in the Northwest Pacific and along the China coast.

Major landfalling typhoons are uncommon in Japan

According to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center, since accurate record-keeping began in 1945, only 16 Category 3 or stronger typhoons have made landfall on one of Japan’s four main islands (Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku, and Hokkaido). Just six of these landfalls were on Japan’s main island of Honshu, where Shanshan is predicted to hit — an average of one strike every 13 years. Two Category 4 typhoons have hit Japan: Shirley of 1965 made landfall in Honshu with 150 mph winds, causing 60 deaths; Yancy of 1993 made landfall on Kyushu with 130 mph winds, killing 48 and doing $3 billion in damage. Japan has experienced only one Category 5 typhoon landfall — the infamous Typhoon Vera of 1959, Japan’s deadliest typhoon, with 5,098 deaths.

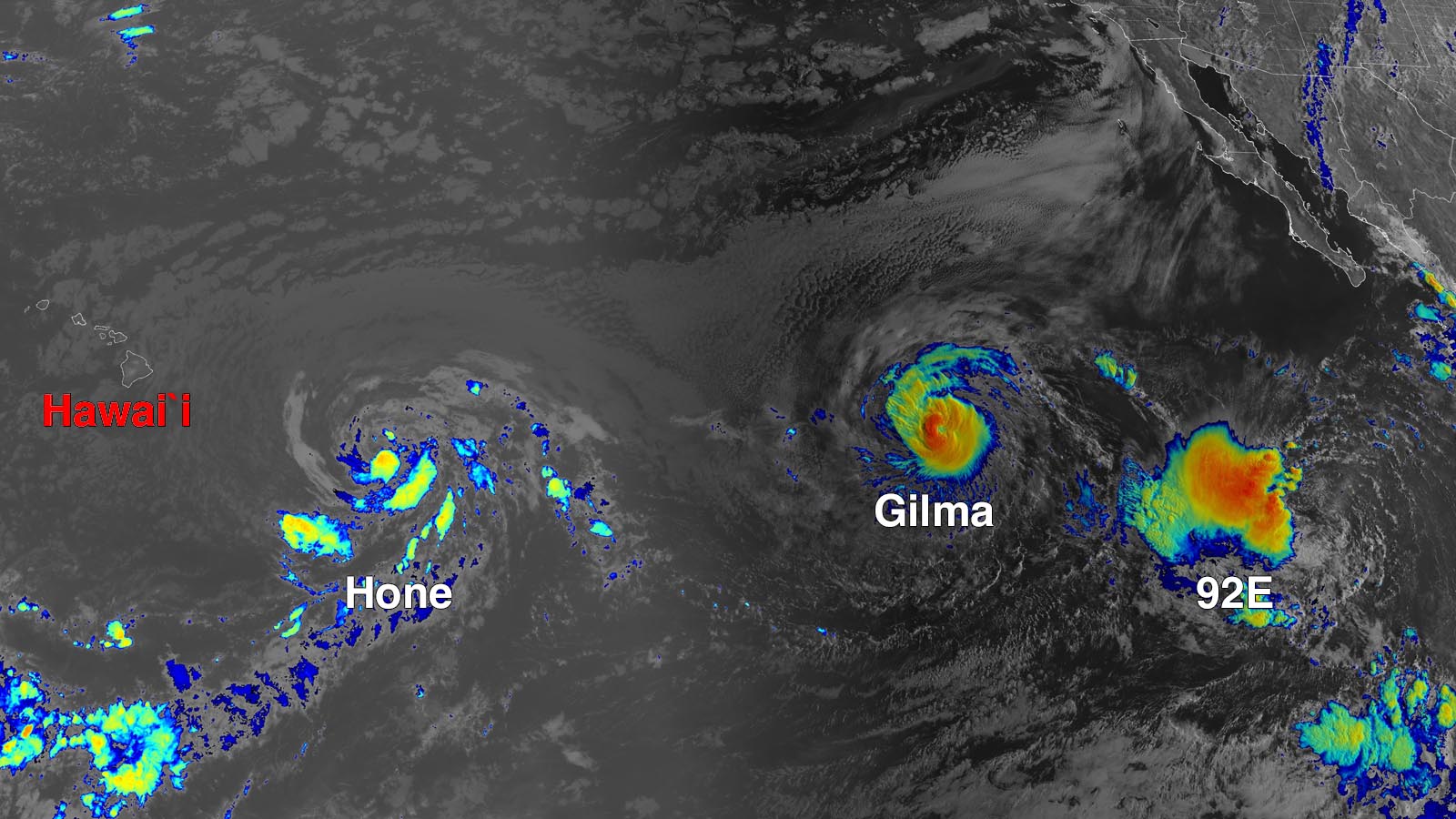

Tropical Storm Hone expected to pass just south of Hawai‘i on Monday

A Tropical Storm Watch is in effect for the Big Island of Hawai‘i, as Tropical Storm Hone gathers strength and heads toward the 50th U.S. state. As of 11 a.m. EDT Friday, Hone was located about 625 miles east-southeast of Hilo, heading west at 16 mph with top winds of 45 mph and a central pressure of 1002 mb. Hone is the first named storm to develop in the Central Pacific since 2019, though a number of others have moved into the region from the Northeast Pacific.

Convection was limited around Hone, and the atmosphere around the storm was not especially moist, with midlevel relative humidity around 55 to 60%. However, wind shear will drop to the light to moderate range this weekend, around 10 knots, and sea surface temperatures of 26-27 degrees Celsius (79-81°F) should be just warm enough for Hone to gradually intensify into a strong tropical storm or Category 1 hurricane. The first hurricane hunter mission into Hone is scheduled for Friday afternoon.

Track models generally agree that Hone will pass well south of the Big Island, but the storm may be close enough to bring gale-force winds, high surf, and heavy rains of four to eight inches to eastern slopes, with strong downslope winds affecting the western slopes. The stronger impacts will be toward the southern half of the island. Much of Hawai‘i is in moderate to severe drought (Fig. 2), so Hone’s rains can be expected to bring considerable drought relief, along with some isolated damaging flooding and power outages.

Well east of Hone in the remote Northeast Pacific – nearly 1800 miles east of Hilo – is potent Hurricane Gilma, the first major hurricane of the 2024 Northeast Pacific season. Gilma was packing top sustained winds of 115 mph at 11 a.m. EDT Friday and was heading west at 8 mph. On Thursday, Gilma reached the upper echelon of Cat 3 strength, as top sustained winds peaked at 125 mph. Gilma will gradually weaken over the next several days as it moves over relatively cool waters and ingests drier air; it will likely be no more than a tropical depression or remnant low when it passes north of Hawai‘i late next week.

Hawai‘i hurricane history

Two named storms affected Hawai‘i in 2023. Tropical Storm Calvin passed about 100 miles to the south of the Big Island on July 18-19, with sustained winds of 45-50 mph. Calvin brought widespread rainfall amounts of two to four inches to the Big Island and Maui, which caused minor flooding and scattered power outages. A few locations on the Big Island received rains of five to seven inches, according to the final report from the National Weather Service.

On August 8-9, 2023, Category 4 Hurricane Dora passed about 700 miles to the south of Hawai‘i. Initial speculation was that Dora might have increased the winds that fanned one of the deadliest wildfires in world history – the Maui fires of 2023, which killed 102 people – although a study released in the journal Weather and Forecasting this month indicates a more important factor may have been an unusually strong subtropical ridge that extended from north of Hawai‘i to the U.S. Southwest. That ridge helped intensify the east-to-west trade winds that were forced over the Maui mountains; in turn, as those strong winds descended toward Lahaina, warming and drying as they flowed downslope, they fanned flames across an area thick with nonnative grasses that had dried out in the summer heat. For more background, see our August 2023 write-up on the situation, “What caused the deadly Hawai‘i wildfires?“

Simply making landfall in Hawai‘i is no small achievement for a tropical cyclone. Only five named systems at tropical storm strength or higher have made landfall in Hawai‘i since 1949:

- Hurricane Dot made landfall on Kauai as a Category 1 hurricane on August 6, 1959, about two weeks before Hawai‘i gained statehood. Dot caused 6 indirect deaths and $6 million in damage (1959 dollars).

- Hurricane Iniki made landfall in Kauai as a Category 4 hurricane on September 11, 1992, killing 6 and causing $1.8 billion in damage (1992 dollars.)

- Tropical Storm Iselle made landfall along the southeast shore of the Big Island, arriving as a 60-mph tropical storm on August 8, 2014. Iselle killed one person and did $79 million in damage (2014 dollars).

- Tropical Storm Darby made landfall along the southeast shore of Hawai‘i’s Big Island on July 23, 2016, with sustained winds of 40 mph. Damage was minimal and there were no deaths.

- Tropical Storm Olivia made landfall on the north shore of both Maui and Lanai on September 12, 2018, with sustained winds of 45 mph. Olivia was blamed for $25 million in damage (2018 dollars).

In addition, Post-Tropical Cyclone Linda hit on Molokai on August 23, 2021, with sustained winds of 40 mph. There were no reports of casualties or damage from Linda.

As defined by the National Hurricane Center, landfall requires the center of a tropical cyclone to pass over land. Other hurricanes and tropical storms have done significant damage on Hawai‘i without making a direct landfall, most notably Lane in 2018 ($250 million 2018 dollars in damage) and Iwa in 1992 ($312 million 1992 dollars in damage). A 2016 modeling study found that we could expect to see a significant increase in hurricanes near Hawai‘i in coming decades due to climate change; see also Jeff Masters’ August 2014 post, “Climate Change May Increase the Number of Hawaiian Hurricanes.”

We help millions of people understand climate change and what to do about it. Help us reach even more people like you.

Source link