“Back to School” signals a change of gear for many, not only for those with school-age children of their own. In response, beach novels are set aside for non-fiction books that can be applied to one’s work.

Coming after months of historic wildfires, widespread western drought, and blistering record-high temperatures in the Pacific Northwest and western Canada, Hurricanes Ida and Nicholas reinforced the “back to school” summons. Striking land in Louisiana as a category 4 hurricane 16 years to the day after Hurricane Katrina had made landfall in 2006, Ida poignantly underscored that the climate was indeed a’changing. And that was before the much weakened Ida still managed to drown Philadelphia, New York City, and northern New Jersey with record rain showers. Then, just 10 days later, Nicholas drenched coastal Texas and Louisiana all over again.

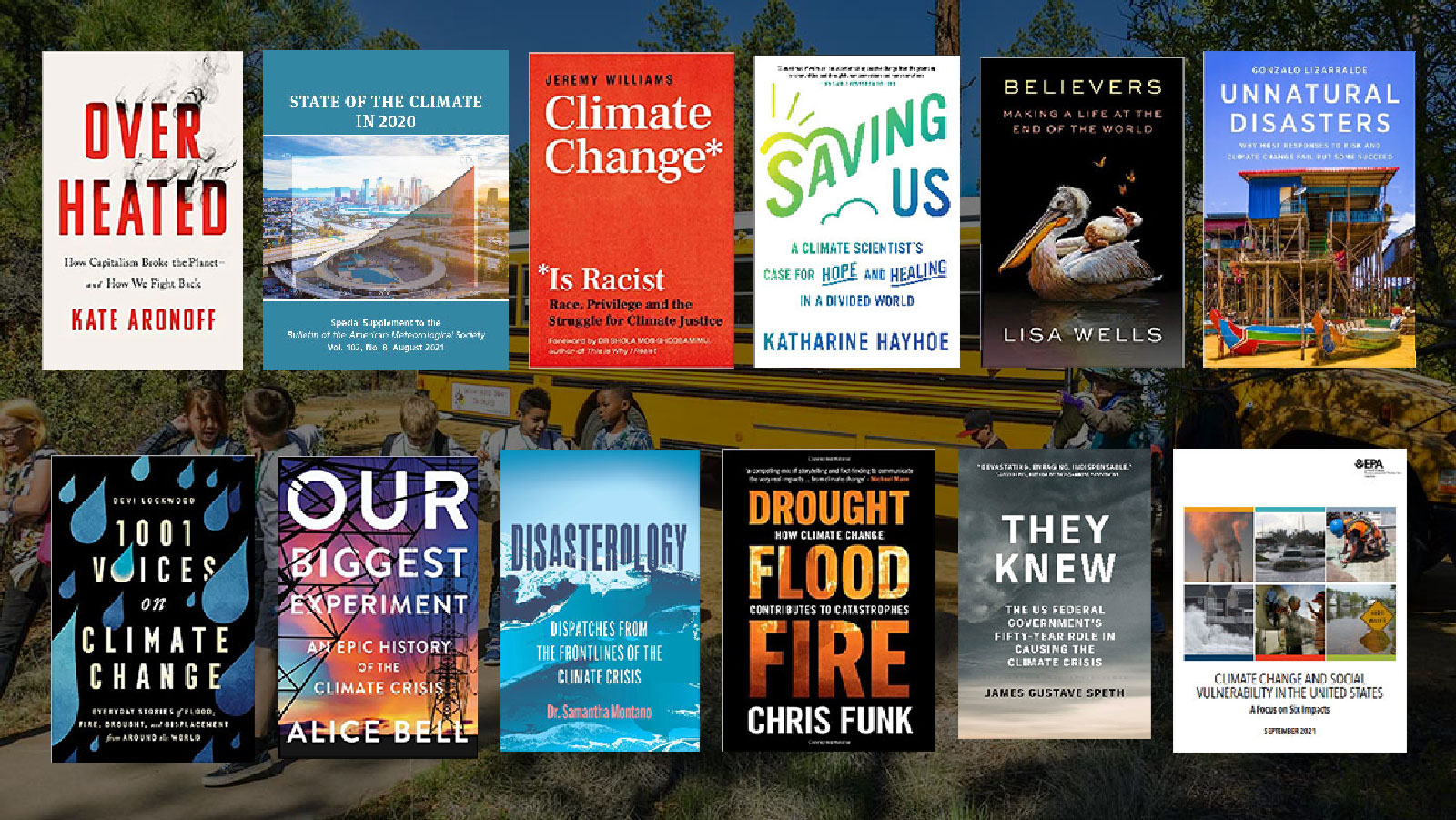

Heeding these converging signals, this month’s bookshelf focuses on very recently published titles that directly address climate change.

Included in the list are two recently published reports, State of the Climate in 2020 from the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society and Climate Change and Social Vulnerability in the United States from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Those two status reports are backed up by two histories of climate science and policy by Alice Bell and James Gustave Speth, three accounts of climate change and “disasterology,” two jeremiads on climate justice, and three somber but hopeful reflections on the lived experience of climate change.

Back to school on climate change indeed.

As always, the descriptions of the books and reports are drawn from copy provided by the companies or organizations that published them.

State of the Climate in 2020 (NOAA/Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2021, 481 pages, free download available here/executive summary available here)

This is the 31st issuance of the annual assessment now known as State of the Climate, published in the Bulletin since 1996. As a supplement to the Bulletin, its foremost function is to document the status and trajectory of many components of the climate system. However, as a series, the report also documents the status and trajectory of our capacity and commitment to observe the climate system. The report, compiled by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, is based on contributions from scientists from around the world. It provides a detailed update on global climate indicators, notable weather events, and other data collected by environmental monitoring stations and instruments located on land, water, ice, and in space.

Editor’s note: See also World Meteorological Organization’s State of the Global Climate 2020.

They Knew: The U.S. Federal Government’s Fifty-Year Role in Causing the Climate Crisis, by James Gustave Speth (The MIT Press 2021, 304 pages, $27.95)

In 2015, a group of 21 young people sued the federal government for violating their constitutional rights by promoting climate catastrophe and thereby depriving them of life, liberty, and property without due process. Tapped by the plaintiffs in Juliana vs United States, environmental lawyer James Gustave Speth analyzed how administrations from Carter to Trump—despite having information about the impending climate crisis and the connection to fossil fuels – continued aggressive support of a fossil fuel based energy system. What did the federal government know and when did it know it? Speth asks, echoing another famous cover-up. They Knew (an updated version of the report Speth prepared for the lawsuit) presents the most definitive indictment yet of the US government’s role in the climate crisis.

Our Biggest Experiment: An Epic History of the Climate Crisis, by Alice Bell (Counterpoint 2021, 288 pages, $26.00)

In Our Biggest Experiment, science communicator Alice Bell takes us back to climate change science’s earliest steps in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, through the point when concern started to rise in the 1950s and right up to today, when the world is finally starting to face up to the reality that things are going to get a lot hotter, a lot drier (in some places), and a lot wetter (in others), with catastrophic consequences. Our Biggest Experiment recounts how the world became addicted to fossil fuels, how we discovered that electricity could be a savior, and how renewable energy is far from a twentieth-century discovery. The message she relays is ultimately hopeful; harnessing the ingenuity and intelligence that has driven the history of climate change research can result in a more sustainable and bearable future for humanity.

Disasterology: Dispatches from the Frontlines of the Climate Crisis, by Samantha Montano (Park Row 2021, 384 pages, $28.99

In Disasterology, Dr. Montano, a disaster researcher, brings readers with her on an eye-opening journey through some of our worst disasters. She explains why we aren’t doing enough to prevent or prepare for disasters, the critical role of media, and how our approach to recovery was not designed to serve marginalized communities. Dr. Montano offers a preview of what will happen to our communities if we don’t take aggressive, immediate action on climate change. In a section devoted to the COVID-19 pandemic, she casts light on the many decisions made behind closed doors that failed to protect the public. A deeply moving and timely narrative that draws on Dr. Montano’s first-hand experience in emergency management, Disasterology is essential reading for anyone who wants to understand how we can better face disasters together.

Drought, Flood, Fire: How Climate Change Contributes to Catastrophes, by Chris Funk (Cambridge University Press 2021, 332 pages, $24.95)

Every year, droughts, floods, and fires impact hundreds of millions of people and cause massive economic losses. Climate change is making these catastrophes more dangerous. Now. Not in the future: NOW. Chris C. Funk’s book combines the latest science with compelling stories to provide a timely, accessible, and beautifully-written synopsis of how climate change is already fomenting dire consequences, and will certainly make things worse in the future. After describing our unique and fragile Earth system, Funk examines recent climate-related disasters and their human consequences. By calling attention to these already occurring impacts, Funk delivers a clarion call for social change, yet also convey hope for our collective future.

Unnatural Disasters: Why Most Responses to Risk and Climate Change Fail But Some Succeed, by Gonzalo Lizarralde (Columbia University Press 2021, 328 pages, $35.00)

Unnatural Disasters offers a new perspective on our most pressing environmental and social challenges, revealing the gaps between abstract concepts like sustainability, resilience, and innovation and the real-world experiences of people living at risk. Gonzalo Lizarralde explains how the causes of disasters are not natural but all too human: inequality, segregation, marginalization, colonialism, neoliberalism, racism, and unrestrained capitalism. He tells the stories of Latin American migrants, Haitian earthquake survivors, Canadian climate activists, African slum dwellers, and other people resisting social and environmental injustices around the world. Lizarralde shows how disasters have become both the causes and consequences of today’s most urgent challenges and proposes achievable solutions to save a planet at risk.

Overheated: How Capitalism Broke the Planet – and How We Fight Back, by Kate Aronoff (Bold Type Books 2021, 432 pages, $30.00)

It has become impossible to deny that the planet is warming, and that governments must act. But a new denialism is taking root in the halls of power, shaped by decades of neoliberal policies and centuries of anti-democratic thinking. Since the 1980s, Democrats and Republicans have each granted enormous concessions to industries hell bent on maintaining business as usual. This approach, journalist Kate Aronoff makes clear, has only made things worse. Drawing on years of reporting, Aronoff lays out an alternative vision, detailing how democratic majorities can curb polluters’ power; create millions of well-paid, union jobs; enact climate reparations; and trans-form the economy into a more leisurely and sustainable one. The fate of our world is at stake.

Climate Change Is Racist: Race, Privilege and the Struggle for Climate Justice, by Jeremy Williams (Icon Books 2021, 208 pages, $16.95 paperback)

When we talk about racism, we often mean personal prejudice or institutional biases. Climate change doesn’t work that way. It is structurally racist, disproportionately caused by majority White people in majority White countries, with the damage unleashed overwhelmingly on people of color. In this eye-opening book, writer and environmental activist Jeremy Williams takes us on a short, urgent journey across the globe – from Kenya to India, the USA to Australia – to understand how White privilege and climate change overlap. We’ll look at the environmental facts, hear the experiences of the people most affected on our planet and learn from the activists leading the change. It’s time for each of us to find our place in the global struggle for justice.

Climate Change and Social Vulnerability in the United States: A Focus on Six Impacts, by Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA 2021,101 pages, free download available here)

Climate change affects all Americans – regardless of socioeconomic status – and many impacts are projected to worsen. But individuals will not equally experience these changes. The EPA’s new report, Climate Change and Social Vulnerability in the United States, improves our understanding of the degree to which four socially vulnerable populations – defined based on income, educational attainment, race and ethnicity, and age – may be more exposed to the highest impacts of climate change. Understanding the comparative risks to vulnerable populations is critical for developing effective and equitable strategies for responding to climate change.

Editor’s note: See also World Meteorological Organization’s Atlas of Mortality and Economic Losses from Weather, Climate, and Water Extremes, 1970–2019 (UN WMO 2021).

Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World, by Katharine Hayhoe (Atria / Simon & Schuster 2021, 320 pages, $27.00)

Called “one of the nation’s most effective communicators on climate change” by The New York Times, Katharine Hayhoe knows how to navigate all sides of the conversation on our changing planet. In Saving Us, Hayhoe argues that when it comes to changing hearts and minds, facts are only one part of the equation. We need to find shared values in order to connect our unique identities to collective action. Drawing on interdisciplinary research and personal stories, Hayhoe shows that small conversations can have astonishing results. Saving Us leaves us with the tools to open a dialogue with your loved ones about how we all can play a role in pushing past doomsday narratives about a planet on fire.

1001 Voices on Climate Change: Everyday Stories of Flood, Fire, Drought, and Displacement from Around the World, by Devi Lockwood (Tiller Press / Simon & Schuster 2021, 352 pages, $26.00)

In 1,001 Voices on Climate Change, Lockwood travels the world, often by bicycle, collecting first-person accounts of climate change. She frequently carried with her a simple cardboard sign reading, “Tell me a story about climate change.” Over five years, covering twenty countries across six continents, Lockwood heard from thousands. From Denmark to China, from Turkey to the Peruvian Amazon, she finds that ordinary people sharing their stories does far more to advance understanding and empathy than even the most alarming statistics and studies. This book is a hopeful global listening tour for climate change, channeling the urgency of those who have already glimpsed the future to help us avoid the worst.

Believers: Making a Life at the End of the World, by Lisa Wells (Farrar, Strau & Giroux 2021, 352 pages, $28.00)

Like most of us, Lisa Wells has spent years overwhelmed by increasingly urgent news of climate change on an apocalyptic scale. She did not need to be convinced of the stakes, but she could not find practical answers. So she embarked on a pilgrimage, tracking down and meeting with people who are dedicated to repairing the earth and seemingly undaunted by the task ahead. Through empathic portraits, Wells shows that these trailblazers are not so far beyond the rest of us. They have accepted that we are living through a global catastrophe. But they are also trying to answer the next question: How do you make a life at the end of the world? Believers demands transformation. It will change how you think about your own actions, about how you can still make an impact, and about how we might yet reckon with our inheritance.

Source link