Author and activist Bill McKibben was a pioneer of the climate change struggle with his seminal 1989 book, The End of Nature, a call to action widely considered the first commercial best-seller to address the issue. Since then, he has founded several organizations for climate activism, most notably 350.org and, most recently, Third Act.

The context

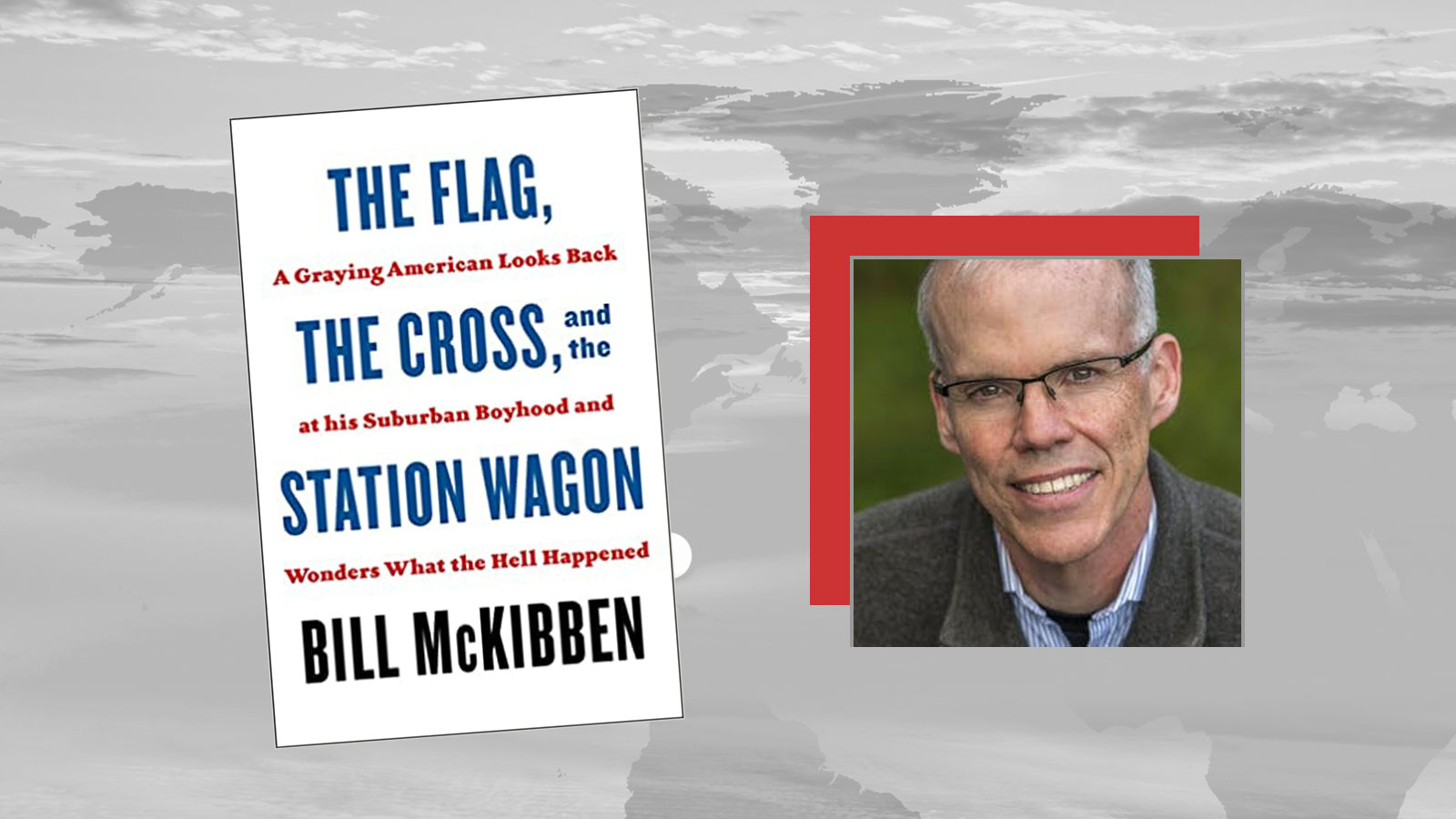

His latest book, The Flag, The Cross, and the Station Wagon: A Graying American Looks Back at His Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened (hereafter “Graying”), is an unusual mix of memoir, social history, and advocacy.

An introductory chapter, “The Setting,” establishes the time and place – the 1970s in Lexington, Massachusetts, where McKibben grew up. The three central chapters are devoted to the roles played in McKibben’s life by the objects named in the title. And in the concluding chapter, “People of a Certain Age,” McKibben talks about Third Act, the organization he founded with the aim of drawing retired baby boomers into climate action. The new book and that new organization both reflect cumulative changes in McKibben’s thinking about climate action.

In his first follow-ups to The End of Nature (see chronological listing here), McKibben experimented with variations on a formula. A description of the problems with modern society’s fossil-fuel-dependent ways of life could precede or follow a description of an Earth-friendly lifestyle. These early books end with a call to action based on shared American values.

But in later works, McKibben acknowledged that more fundamental conflicts of values underlie political differences over climate change. In Oil and Honey (2014), he described what he learned about oil companies and their tactics while protesting the Keystone XL Pipeline. In Falter (2019), he delved into American popular culture and techno-futurism, devoting a chapter to the pernicious influence Ayn Rand’s novels about heroic entrepreneurs had on conservatives’ views of the economy, the environment, and government. The “American” values to which he had confidently appealed in his previous calls to action, McKibben concluded, were not as widely shared or as durable as he had assumed.

Now “graying,” McKibben uses episodes from his New England life to describe how Americans’ ideas about patriotism, religion, and economics have changed in the past five decades. In the process, he also explains the uniquely favored position baby boomers occupied in American socio-economic history and, as a result, the unique obligation they now have to act.

Underlying these stories are the socio-economic facts of the period. The three decades after World War II were notable for their prosperity. But opportunity was not shared equally. Discriminatory practices made it much more difficult for African Americans and other people of color to lay the same foundations for success as their white peers. The movements organized in protest of these injustices forced all Americans to make a choice: honor the values they professed in their civic spaces, churches, and marketplaces … or revise what they professed. The choices made by different factions in those years still influence the current politics of climate change.

The flag and the cross

Growing up in a town steeped in Revolutionary-era history, McKibben was imbued with patriotism from an early age. In high school, he became a tour guide in his hometown, narrating the intertwined stories of Paul Revere and the battle of Lexington and Concord as he led visitors through the historic district.

Even then, however, he was dimly aware of gaps in the tales he told. “The obvious problem with this glorification of American history is that the egalitarian impulse that drove the Revolution didn’t apply to everyone.” Although part of Lexington’s history from the very beginning, the roles African-Americans could play were limited, and even in those roles they were often omitted from official accounts, as they were from McKibben’s tour script.

McKibben recounts what he has since learned about the roles Blacks played in New England’s history, from historians such as Ta-Nehisi Coates and Nikole Hannah-Jones. Only when people are remembered, he notes, can their moral claims be heard. One claim, about the cumulative impact of slavery, segregation, and discrimination, he summarizes in a simple, if dated, ratio: “In 2014, for every dollar in a white household, a Black household had less than seven cents.”

Precisely to avoid such discomforting numbers, some conservatives want to limit what their children learn about the past, in part by banning these historians’ books from classrooms and school libraries. In his conclusion to “The Flag,” McKibben insists that we see and listen. “What we choose to do [in response] will help us figure out whether ‘all men are created equal’ was an awkward lie or a promise that took much too long to fulfill.”

In “The Cross,” McKibben offers an analogous retrospective of his experiences with American Christianity, starting with the historic Hancock Church his family attended in Lexington. And not just church services. McKibben attended Sunday school, participated in service work, and went away each summer on youth retreats at synod campgrounds.

Here it is the gospels’ frequent verses about ministering to the poor and to the suffering that pose the moral challenge. Practitioners of the “social gospel” who McKibben encountered in high school and college took the challenge head on, devising programs to reduce poverty and to alleviate the suffering and alienation of those on the margins of society. But as a young reporter, first for his local newspaper and then for the Harvard Crimson, McKibben encountered versions of the “prosperity gospel,” in which poverty marks a deficit of faith.

These Christians reinterpreted scripture so that they could ignore rising inequality. And as one of the major subgroups of Evangelicalism, they became a mainstay for Donald Trump.

The station wagon

With “The Station Wagon,” McKibben shifts gears, focusing less on the opportunity and wealth gaps between blacks and whites and more on the gaps between generations and between Americans and the people of the global south. The causes and consequences of climate change emerge as critical factors.

Here it is worth noting again the unique circumstances of the post-war economy. Strong labor unions, technological advances spurred by years of wartime R&D, and high marginal tax rates that financed ambitious government investments in education and infrastructure delivered more wealth to the middle and bottom … and less to the top. The result: higher standards of living with lower inequality, the squarest economic deal in American history.

If the same conditions applied today, McKibben notes, citing a Rand Corporation study, everyone’s income would get a significant boost.

“Are you a college-educated, prime-aged, full-time worker earning $72,000?” McKibben rhetorically asks his readers. “Rising inequality is costing you between $48,000 and $63,000 a year.”

Benefiting from such a boost during the first decades of their careers, boomers were able to earn more money more quickly, incur much less debt, and buy into a decades-long run-up in real estate. “When baby boomers were millennials’ age,” a 2019 study found, “they held seven times the wealth millennials do.”

This generational inequality then led to another inequality, the result of another moral choice.

By the end of the 1970s, McKibben explains, President Jimmy Carter, still dealing with the reverberations of “the energy crisis,” had become an avid proponent of solar power, even installing solar water healing panels on the roof of the White House. He had also been briefed on “the possibility of catastrophic climate change.” Had Carter won the opportunity to execute his plans – “he said a fifth of the country’s energy should come from solar power by 2000” – the country and the world might have followed a different path.

Instead, Americans voted for Ronald Reagan, the candidate who dismissed concerns for climate change and who promised to get America moving again – with new sources of fossil fuels. The solar panels were stripped off the White House roof, renewable energy plans were scrapped, and taxes that financed federal education and social programs were cut. The chance to model an alternative energy economy for the developing world was forfeited.

With their choice in the 1980 election, boomers proved to be “better consumers than citizens,” buying, in the years that followed, bigger houses, bigger cars, and more and more stuff to put in them, burning billions of barrels of oil in the process. As much as 90 percent of the world’s fossil fuel emissions has occurred in boomer’s lifetimes.

By refusing to change course, Americans committed the world to a more dangerous climate.

“The choices we made in those years around 1980 will turn out to be more important than any choices any nation ever made,” McKibben writes. “They’ll be visible in the geological record long after everything else is forgotten.”

Third acts

If enjoying an unequally distributed benefit incurs a debt, then boomers have shares in three:

1) the debt owed to African-Americans for injustices suffered over the past 400 years;

2) the debt owed to millennials for opportunities they never received; and

3) the debt owed to the people of the global south for climate-changed losses and damages they’ll endure though having had virtually no role in their creation.

The way for boomers to discharge their portions of these national debts, McKibben argues in the concluding chapter of his book, is to devote some of their Third Acts, their retirements, to social activism. In particular, he encourages boomers to engage in nonviolent protest. He recounts, with pride, the protest in which 60-, 70-, 80-, and even 90-year olds chained themselves to the White House fence, all the better to pressure former President Barack Obama to cancel the Keystone XL pipeline. In this way, boomers can spare millennials, heavily burdened by debts most boomers avoided, the financial and professional risks of symbolic arrests.

This review only outlines McKibben’s challenging new book. It omits what McKibben actually learned from Ta-Nehisi Coates and Nikole Hannah-Jones about New England history; those stories will surprise most readers. For sake of brevity, it also could not include the charismatic religious leaders McKibben encountered in history or in person. And it does not touch on the many entertaining intersections of personal and national history, like the story about how McKibben came into possession of solar water heater panels that had been atop President Carter’s White House. “Graying” will entertain readers even as it changes their understanding of the climate crisis.

Finally, although released before the Supreme Court decisions on guns, access to abortions, and EPA regulatory authority on power plant emissions were announced, before the heat waves in the U.S. and Europe set new records, and before the surprising late July resurrection of climate legislation, McKibben’s book will help readers place these events in context. This is a generation-defining moment for social and climate justice, a moment that requires unprecedented cooperation across races, genders, generations, and geographies. And in this moment one generation, the boomers, can and should play a pivotal role.

While they were growing up, middle class white boomers, like Bill McKibben, enjoyed the squarest deal in American history, thanks to government policies and programs that protected unions, supported education, and invested expansively in infrastructure – all financed by much higher marginal tax rates.

Thus, boomers are uniquely positioned to help their fellow Americans remember, recover, and expand that square deal – for people of all colors and generations and for the planet on which they live. And that square deal might ensure an America still bounded by 2C.

Source link