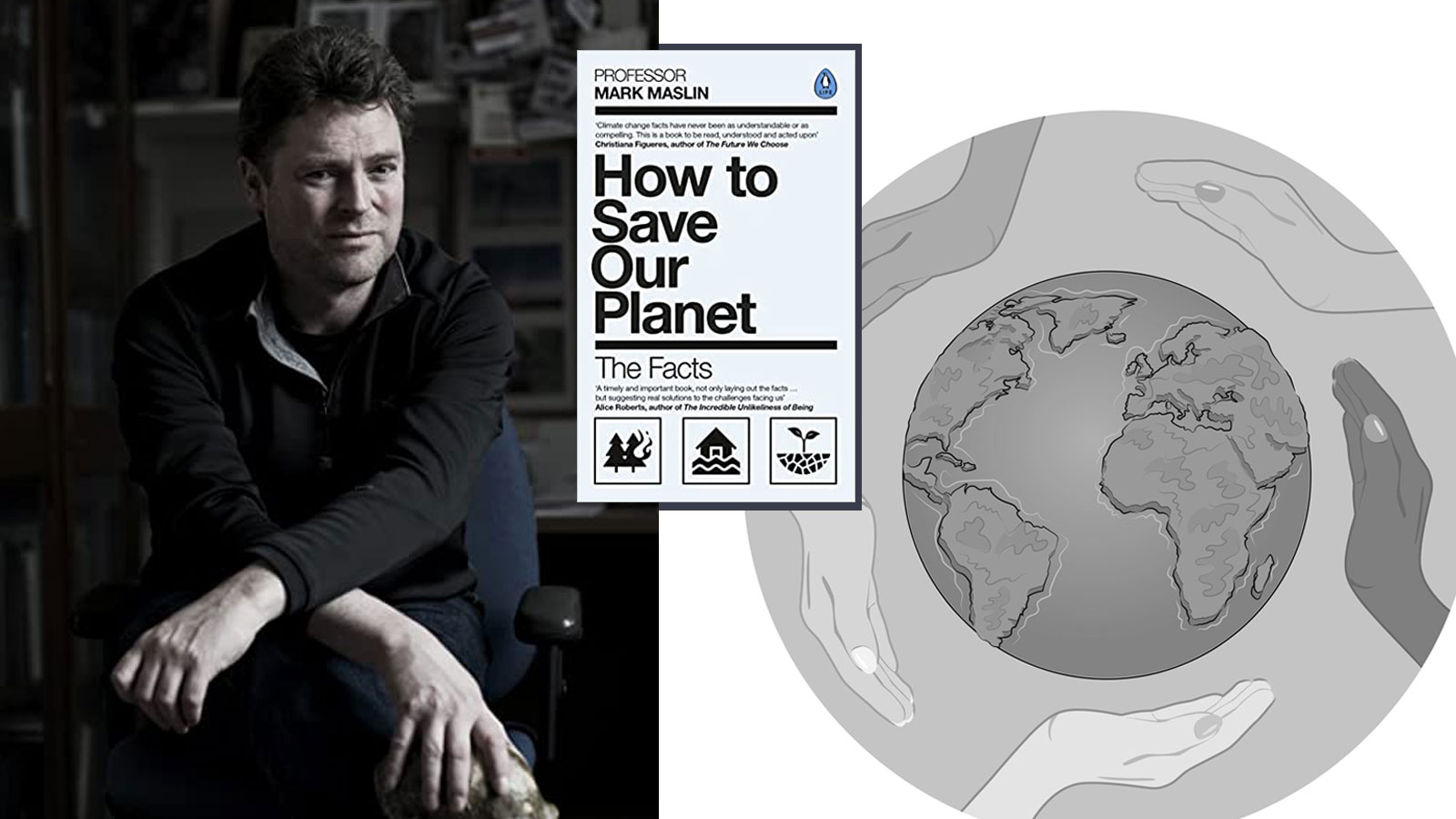

This is an important book. And its author is a smart guy. Starting from the premise that facts matter, University College London (UCL) professor of Earth system science Mark Maslin arranges a long list of depressing, inspiring, familiar, and surprising facts about climate change, making How to Save Our Planet a field guide to what Maslin calls “the greatest threat we have ever faced.”

“We stand at the precipice,” Maslin writes. “The future of the planet is in our hands.”

Deliberately fast paced, with large print, generous white space, and quick, simple sentences, How to Save Our Planet is a quick read. Indeed, some pages contain a single fact, injunction, or question, from “Demand action” to “Do you need fast fashion?”

In short, this is a book you can quote in the pub, at the breakfast table, and before politicians and policy makers.

Inspired by The Art of War – a book-length series of short, sharp, trenchant insights into war – How to Save the Planet insists that society needs to be put on war footing. As 6th century BC military strategist Sun Tzu noted 2,500 years ago, planning and preparation are imperatives because the art of war “is a matter of life and death, a road either to safety or to ruin.”

Ditto the art of climate change: Either we get it right or we get it terribly wrong.

Sobering climate data, things looking bad, but ‘they can be turned around.’

But if it was inspired by The Art of War, How to Save Our Planet is most like Ten Billion, minus its self-indulgent pessimism and controversial, if memorable, parting shot. On page after relentless page, Stephen Emmott documents the staggering impact humans have had on the planet, ultimately concluding in the book’s final sentence, “I think we’re f***ed.” (In the original, spelled out)

No, we’re not, Maslin counters. As bad as things are environmentally, they can be turned around. Across nine brisk, self-contained chapters – designed to be read in any order – he mixes plenty of sobering statistics (like Emmott) with lots of sound advice (unlike Emmott, who advises us to teach our children how to use a gun for the coming eco-apocalypse).

Frankly, Maslin’s can-do optimism is refreshing.

Although chapter two, “History of Humanity,” is a bit Eurocentric, chapter six, “Power of the Individual,” embraces a theory of history that change comes only from the bottom-up, when every-day people organize in the common commitment to a different future, insisting that things don’t have to be this way and that governments can be convinced to change course. To quote the late historian and playwright Howard Zinn, “Small acts, when multiplied by millions of people, can transform the world.”

Put simply: What is government for?

Taking aim at a big question, Maslin asks what is government for? His answer is at once simple and profound: to articulate a shared vision of the common good and to put in place policies to realize it.

Of course, that’s easier said than done. Consumer capitalism – that three-way suicide pact among corporations that make junk we don’t need, governments that refuse to put regulations in place, and consumers that fashion their identity through the things they buy – is the only game in town. And climate denial – which is basically a murder plot – may be the punchline on late-night television, but it’s no joke. Together, they make bold, ambitious climate action an uphill battle. Not surprisingly, Maslin reserves a special contempt for conspicuous consumption (“You do not need all that stuff”), for servile governments (“Since the 1980s and the fall of communism, neoliberalism has been the dominant economic theory in Western government policies”), and for climate denial (“The gods themselves struggle vainly with the righteousness of self-interest”).

How to Save Our Planet is a high-speed antidote to climate despair. Bottom line, we aren’t f***ed unless we choose to be: “All of us, if we have the courage, can create a better, fairer, safer future.”

Publisher: Penguin UK, 2021 (256 pages)

Source link