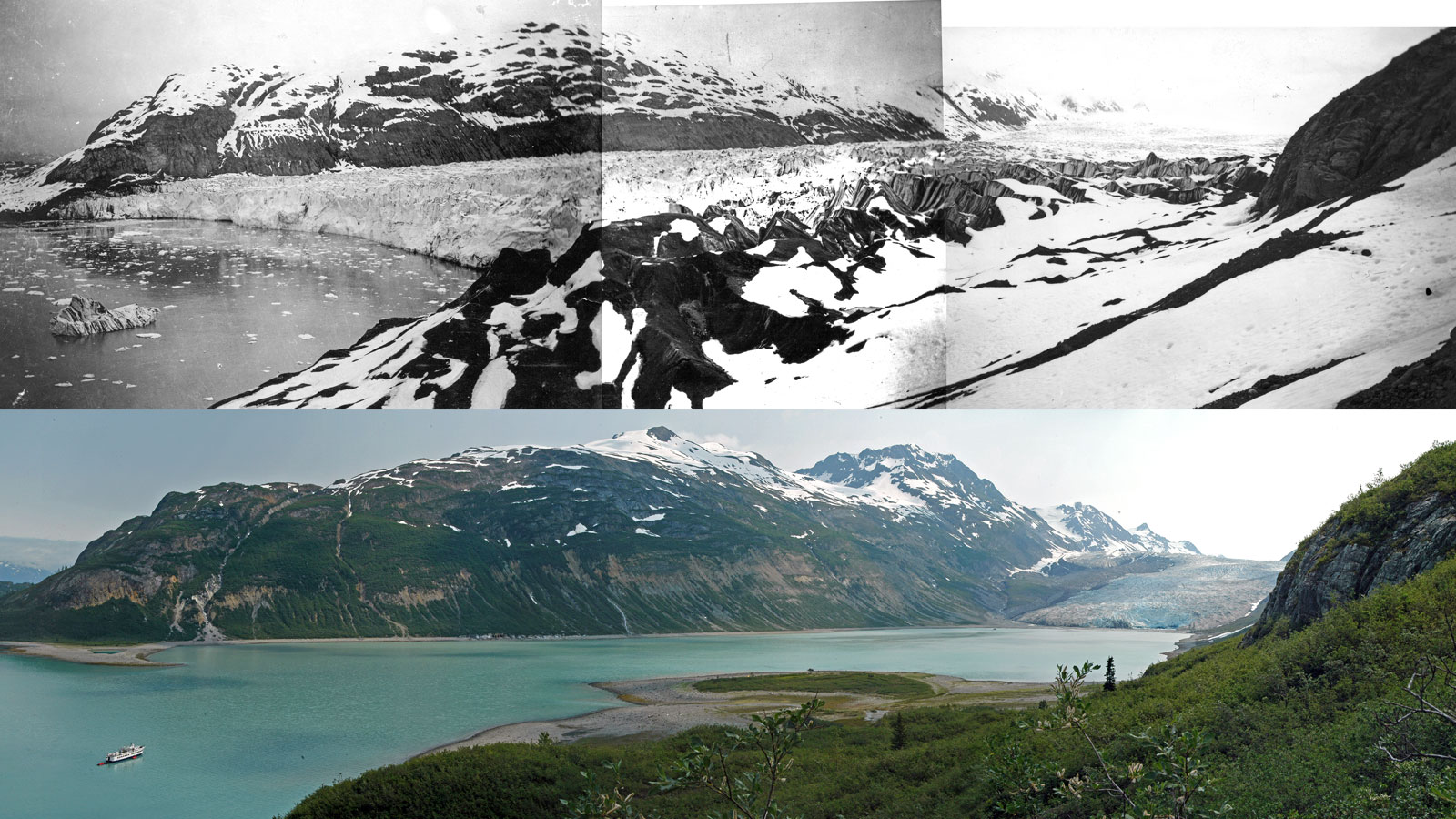

A 2004 photo captures a boat cruising a strip of water where an 1899 picture taken from the same spot shows a giant glacier. On either side of the channel, green trees and shrubs cover a rocky landscape that a century ago had been blanketed with white snow.

Armed with historical photographs of the Alaskan landscape, Ron Karpilo climbed mountains, rafted rivers, and traveled deep into the wilderness to take photos from the exact vantage points used by earlier photographers. His goal: illustrate how the changing climate has melted glaciers, spurred plant growth, and made other drastic transformations to natural vistas.

Craning his neck to scan the ridge line, Karpilo was deep in concentration, working to find just the right spot in Denali National Park to take a photograph. A research associate geologist with Colorado State University, he was trying to take a photo from the exact spot used by geologist Stephen Reid Capps in Denali nearly a century earlier.

Karpilo’s photographs are valuable research tools for geologists, glaciologists, hydrologists, ecologists, and other specialists. Furthermore, they provide a stunning introduction for non-experts into the real-life effects of climate change.

“Anyone from my [six year old] son … to someone who has a PhD in geology, they can see and study changes in the photos,” Karpilo says. “I could show a photo where in 1899 there’s a glacier and then in 2021 there’s no glacier.”

“People don’t get their eyes glazed over” as can happen when “you’re showing them equations, he says. “You’re showing pretty pictures of Alaska, and they get interested, and so it kind of hooks them and makes it so they can understand. Everyone’s taken pictures, everyone can see what’s happening. And so it’s really a tool that speaks to anyone, and that’s my favorite part about it.”

“When you show a glacier that’s just not there anymore, it’s hard to dispute,” Karpilo says. “It’s disappearing … something is changing, and so that’s what’s made it such a good tool.”

Photo buffs join in showing warming impacts

Repeat photography is attracting amateurs to join with professionals in building a treasury of images to show how climate change has affected areas all over the world.

In Alaska Park Science, Karpilo discussed how he had painstakingly researched the old photos and did his best to recreate them in several Alaskan national parks, including Glacier Bay, Denali, Gates of the Arctic, and Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. He did not just stick his camera out the car window and click: The project involved extensive backpacking and packrafting trips into the wilds of Denali. In Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, he trekked the arduous 33-mile-long Chilkoot Trail – twice. His team traveled via bush plane to Gates of the Arctic, and the pilot dropped them off in a location nearly 100 miles from the nearest village.

The work was physically demanding, but Karpilo says the most difficult part involved finding the exact spot where each earlier photograph was taken in order to take the new shot. In some areas, 30 to 40-foot-tall walls of vegetation have taken the place of once wide-open vistas.

“It’s frustrating where you get to the spot where you’re pretty sure the photo was taken, but all you see are leaves, branches, and bushes,” Karpilo says. “That definitely shows that things have changed, and vegetation has grown in those places.”

“It’s sort of like time travel where you can go back in time over a century and see what things looked like, find old photos, and I wonder what this place looked like 100 years ago.”

“You can answer that question,” he says. “I feel like I’m creating time capsules when I establish a new photo station.”

Repeat photography is used in a number of parks and areas throughout the U.S., as with a Glacier National Park project to capture glaciers over time.

A volunteer citizen science tool, Chronoglog, allows people to contribute to repeat photography projects at participating sites throughout the U.S., and in a few locations abroad. These sites include Pass Mountain Overlook in Shenandoah National Park, Keālia Ponds in Hawaii, and freshwater tidal wetlands near Washington, D.C.

One such site is about 90 miles outside of Houston, Texas. Big Thicket National Preserve’s Chronolog Time-Lapse Project allows visitors to snap images in three different park locations and upload them to the website, which will use the photos to create a time-lapse of the site. Special stations with smartphone holders are mounted alongside trails to help visitors precisely position their phones to capture the same scene and angle as used by previous photographers. Visitors’ uploaded images to the website are incorporated in a timeline of photos depicting change over time.

With then/now images, ‘it will be interesting to see what we see.’

The preserve’s Chronolog sites include the Pitcher Plant Trail where a boardwalk runs alongside a marshy area with carnivorous pitcher plants; Kirby Nature Trail, which includes a tupelo and bald cypress slough; and Longleaf Pine Restoration Area, where 100,000 saplings have been planted in the “Centennial Forest” in honor of the National Park Service’s one-hundredth anniversary.

“We are planning on using sections of the pictures for educational purposes through some of our field trips showing how the landscape can change whether through human change or natural progress,” says Megan Urban, chief of interpretation and education at Big Thicket National Preserve.

The Chronolog sites in Big Thicket are relatively new, but in coming years they may capture a plethora of changes, from natural variations to human-caused changes like prescribed fire and climate-related impacts.

“With the climate impact, probably the biggest change we could potentially see is if we have, year after year, hurricanes that come through here,” Urban says. “Is there enough time for these ecosystems to repair themselves before the next hurricane? If we’re seeing stronger hurricanes, then we might be seeing more and more downed trees.” She also points to the potential impacts of climate change-related dry spells and how such hydrological changes may impact vegetation. “It will be interesting to see what we see,” she says.

What will these images reveal in 100 years? It’s hard to say for sure, but collecting current images will help chronicle changes over coming decades, allowing scientists and amateurs alike an opportunity to learn about the past and present, and creating a time capsule of sorts.

Source link