If you had on your 2023 weird-weather Bingo card that the first major U.S. cities to be in the National Hurricane Center’s cone of uncertainty this hurricane season would be San Diego and Los Angeles, it’s payday time.

It’s very rare to see Southern California placed in the forecast cone for a hurricane, and this large and very wet hurricane poses a rare significant heavy rain threat for the Southwest U.S. early next week.

Track forecast for Hilary

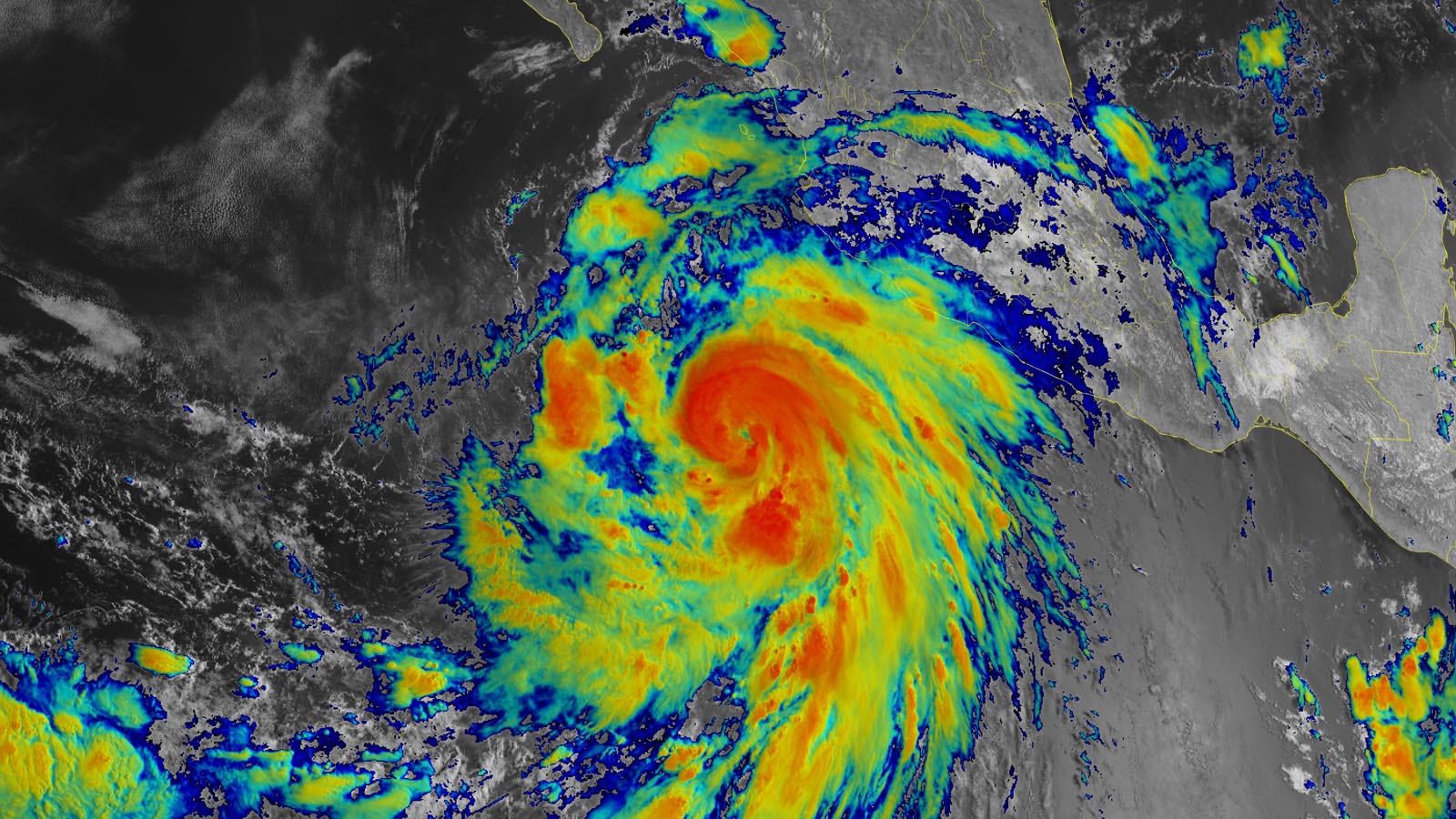

As of 11 a.m. EDT Thursday, Hilary was a category 1 storm with top sustained winds of 85 mph and a central pressure of 980 mb, located about 365 miles south-southwest of the tip of Mexico’s Baja California Peninsula, headed west-northwest at 14 mph. Heavy rains from the hurricane were affecting portions of southwest Mexico, and an outer spiral band from the hurricane was approaching the southern tip of the Baja Peninsula. Hilary had rapidly intensified by 45 mph in the 24 hours since it formed at 11 a.m. EDT Wednesday.

A trough of low pressure off the California coast and a near-record-strength ridge of high pressure over the central U.S. will provide a well-defined steering flow for Hilary, turning the storm to the northwest on Friday and north-northwest on Saturday, taking the hurricane on a course roughly parallel to the coast of Baja Mexico. On this track, Hilary will bring heavy rains to Baja beginning on Thursday evening, with these rains spreading northward along the peninsula through the weekend.

The hurricane is embedded in a very moist air mass, with midlevel relative humidity around 80%. Rainfall amounts of three to six inches are possible throughout Baja California, with localized totals of 10 inches on the peninsula, bringing the risk of flash floods and mudslides in mountainous areas.

Intensity forecast for Hilary

Hilary has nearly ideal conditions for intensification over the next two days, with warm ocean waters near 30 degrees Celsius (86°F), low wind shear, and a very moist atmosphere. The SHIPS, LGEM, and HAFS-B intensity models and the official NHC forecast are very bullish with the intensity forecast, with NHC calling for Hilary to peak as a major category 4 hurricane on Saturday, when it will be making its closest approach to the southern tip of the Baja Peninsula. The 12Z Thursday SHIPS model gave Hilary a 100% chance of rapidly intensifying by at least 50 mph in 36 hours – an unusually aggressive forecast of rapid intensification. However, three of our top dynamical intensity models – the HAFS-A, HMON, and HWRF models – were much less aggressive, calling for Hilary to peak as a category 2 storm on Saturday. Thus, the intensity forecast has considerable uncertainty.

By Sunday morning, Hilary will be moving over much colder waters near 24 degrees Celsius (75°F), the surrounding atmosphere will become drier and more stable, and wind shear is predicted to increase. These factors are likely to cause rapid weakening of Hilary. In addition, Hilary may come close enough to the coast of Baja for land interaction to significantly weaken the hurricane.

However, Hilary is a large hurricane and is predicted to have tropical-storm-force winds spanning more than 470 miles on Sunday. So although rapid weakening is a safe bet, Hilary may not spin down quite as quickly as a smaller hurricane might. The National Hurricane Center is predicting that Hilary will be a strong tropical storm with 60 mph winds on Monday morning, when it was predicted to be near San Diego. In its 11 a.m. EDT Thursday wind probability forecast, NHC gave San Diego a 41% chance of experiencing tropical storm-force winds by Monday morning; Long Beach near Los Angeles was given a 28% chance.

Hilary’s winds may bring a storm surge of several feet to the Southern California coast if the center remains offshore, and large waves and high surf can be expected to cause damaging coastal erosion. But the biggest threat from Hilary to the Southwest U.S. is likely to be heavy rains. The National Weather Service Weather Prediction Center took the unusual step of issuing a “moderate” risk outlook for excessive rains leading to flash flooding Sunday morning through Monday morning over parts of the far Southern California desert, where two to four inches of rain can be expected, with isolated higher amounts of eight inches in mountainous areas.

Tropical cyclones: rare visitors to California

Few tropical storms and hurricanes have affected California because the Pacific waters off the coast of Southern California and far northern Baja California are too cool to sustain a tropical storm or hurricane for very long. In any event, most tropical cyclones from the northeast Pacific recurve before they reach the latitudes of San Diego or Los Angeles.

It requires an extraordinarily unusual blend of ingredients to allow a tropical cyclone to take just the right (or wrong!) trajectory quickly enough to reach Southern California before it has decayed into a post-tropical or remnant cyclone. It’s much more common for such a cyclone to arrive in the United States without widespread tropical-storm-force winds but with a shield of heavy rain that can extend into parts of the Southwest and Great Basin, and sometimes even into the Great Plains. (The remnants of Hurricane Tico dropped seven to 17 inches of rain in a band over parts of Texas and Oklahoma in October 1983, causing widespread flooding and taking at least six lives.)

Kristen Corbosiero, who is now an associate professor of meteorology at the University at Albany, State University of New York, led a 2009 study that examined 35 Eastern Pacific tropical storms or hurricanes that brought significant rainfall to the southwestern United States from 1958 to 2003. These systems represented less than 10% of all of the Eastern Pacific’s named storms during that time, but they accounted for more than 20% of all the warm-season precipitation falling in southern California and northern Baja California. Of these 35 systems, only five affected the U.S. as early as Aug. 21, and most were in September, so the arrival of Hilary’s impacts on or around Monday would be an early outlier.

Since 1850, Southern California has experienced strong winds from at least eight tropical cyclones or their remnants. The most recent of these was Hurricane Kay of 2022, which intensified to a category 2 hurricane off the coast of Mexico’s Baja Peninsula before weakening to a category 1 storm and making landfall with 75 mph winds along the central Baja coast on Sept. 8. Kay rapidly weakened and turned out to sea after landfall, dissipating a few hundred miles southwest of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Kay brought rains of three to six inches to Baja Mexico, with isolated amounts in excess of eight inches. Kay killed four people and brought over $3 million in damage to Mexico. Moisture associated with the hurricane flowed into Southern California, Arizona, and Nevada, bringing widespread heavy rains of two to six inches, flash floods, and damaging winds. Damage in the U.S. was estimated at $7 million, mostly in California, and a debris flow in Southern California killed one person. A wind gust to 109 mph was reported at Cuyamaca Peak in San Diego County as Kay was passing well to the south.

Only two systems are known to have made it far enough north while still offshore to bring tropical storm conditions to the coast of Southern California:

1858: A northeast Pacific hurricane accelerated north-northeast in early October 1858, approaching San Diego on Oct. 2 before veering westward. The city had only a few hundred permanent residents at the time.

Independent scholar Michael Chenoweth teamed with Chris Landsea of the National Hurricane Center in 2004 for an analysis of the storm (see PDF). At the New San Diego port, the barometric pressure dropped from 29.91 inches at 7 a.m. PST on Oct. 2 to 29.50 inches (994 millibars) at 2 p.m., which according to Chenoweth and Landsea suggests winds of at least 65 mph. The weather observer at the New San Diego port remarked: “A great storm, causing the air to be filled with dense clouds of dust, some of the houses were unroofed and blown down, trees uprooted, and fences destroyed.” Along these lines, a San Diego correspondent for the Daily Alta California reported that “several very heavy gusts of wind came driving madly along, completely filling the whole atmosphere with thick and impenetrable clouds of dust and sand … this continued for a considerable length of time, the violence of the wind still increasing, until about one o’clock, when it came along in a perfect hurricane, tearing down houses and everything that was in its way.”

1939: A northeast Pacific hurricane (at least a category 2 when it was off the coast of Baja, according to historical hurricane expert Cary Mock) weakened to a tropical storm about 100-150 miles off the coast of California before making landfall in Los Angeles near San Pedro, California, on Sept. 25 with sustained winds of 65 mph and a central pressure of 994 mb. The trajectory pushed great volumes of moisture against the coastal ranges from Los Angeles southward, leading to widespread flooding from torrential rains that totaled 11.60 inches (295 millimeters) at Mount Wilson and 5.66 inches (133 millimeters) in downtown Los Angeles. Wind gusts reached 65 mph at Long Beach. According to NOAA, flooding from the storm killed 45 people in Southern California, and another 48 died aboard two ships that sank near the coast.

“The storm turned the sea into a raging force as huge waves pummeled the Alamitos Peninsula and Belmont Shore, yanking 10 homes off their foundations and washing them out to sea, while reducing scores of others to driftwood kindling,” the Long Beach Post reported in a 2019 retrospective. The tropical storm arrived after an intense, prolonged heat wave that brought temperatures of over 100°F to the region. Many beachgoers attracted to the ocean to cool off lost their lives when the floods from the storm unexpectedly hit, according to Mock.

Three threat areas to watch in the Atlantic

In the Atlantic, the area of most immediate concern to monitor is in the Gulf of Mexico. A tropical wave in the eastern Caribbean is expected to enter the Gulf of Mexico by Sunday and interact with the remnants of an old cold front. Upper-level winds are predicted to be favorable for development, and with record-warm ocean temperatures in the Gulf, a tropical depression could form by Monday.

Anything that forms will be steered mostly to the west, resulting in the greatest threat to Texas, Louisiana, and/or the coast of northern Mexico, south of the Texas border. However, the system will likely not have enough time over water to intensify much. Although some members of the Thursday morning runs of the GFS and European model ensembles do develop something in the Gulf early next week, none of the forecasts show the system reaching hurricane strength. Much of the coast of Texas and Louisiana is in severe drought, and the rains from this predicted tropical disturbance are likely to bring some beneficial drought relief. In their 8 a.m. EDT Thursday Tropical Weather Outlook, the National Hurricane Center, or NHC, gave two-day and seven-day odds of development of 0% and 30%, respectively, to the future Gulf of Mexico disturbance.

NHC is also watching two tropical waves in the tropical Atlantic, which recent runs of the GFS and European ensemble models have been showing could develop over the next week. Both of these tropical waves are being given two-day and seven-day odds of development of 40% and 60%, respectively. However, both are headed west-northwest, on a track that will likely miss the Caribbean. The easternmost wave nearest the coast of Africa has been designated Invest 98L by the National Hurricane Center; the wave to its west is called Invest 99L. Residents of the Lesser Antilles will want to monitor the progress of Invest 99L, the westernmost disturbance. Dry air and wind shear will impede development of both of these waves.

The next name on the Atlantic list of storms is Emily. It has been more than three weeks since Category 1 Hurricane Don, the Atlantic’s only hurricane of 2023 thus far, became a post-tropical cyclone on July 24.

Website visitors can comment on “Eye on the Storm” posts (see comments policy below). Sign up to receive notices of new postings here.