Near-record-warm waters along the northern Gulf Coast will be turning up the burners on thunderstorm development near a stalled front. The likely result will be pulses of torrential rain, extending over much or most of the next week across coastal regions that are accustomed to intensely wet weather but still vulnerable to major flooding.

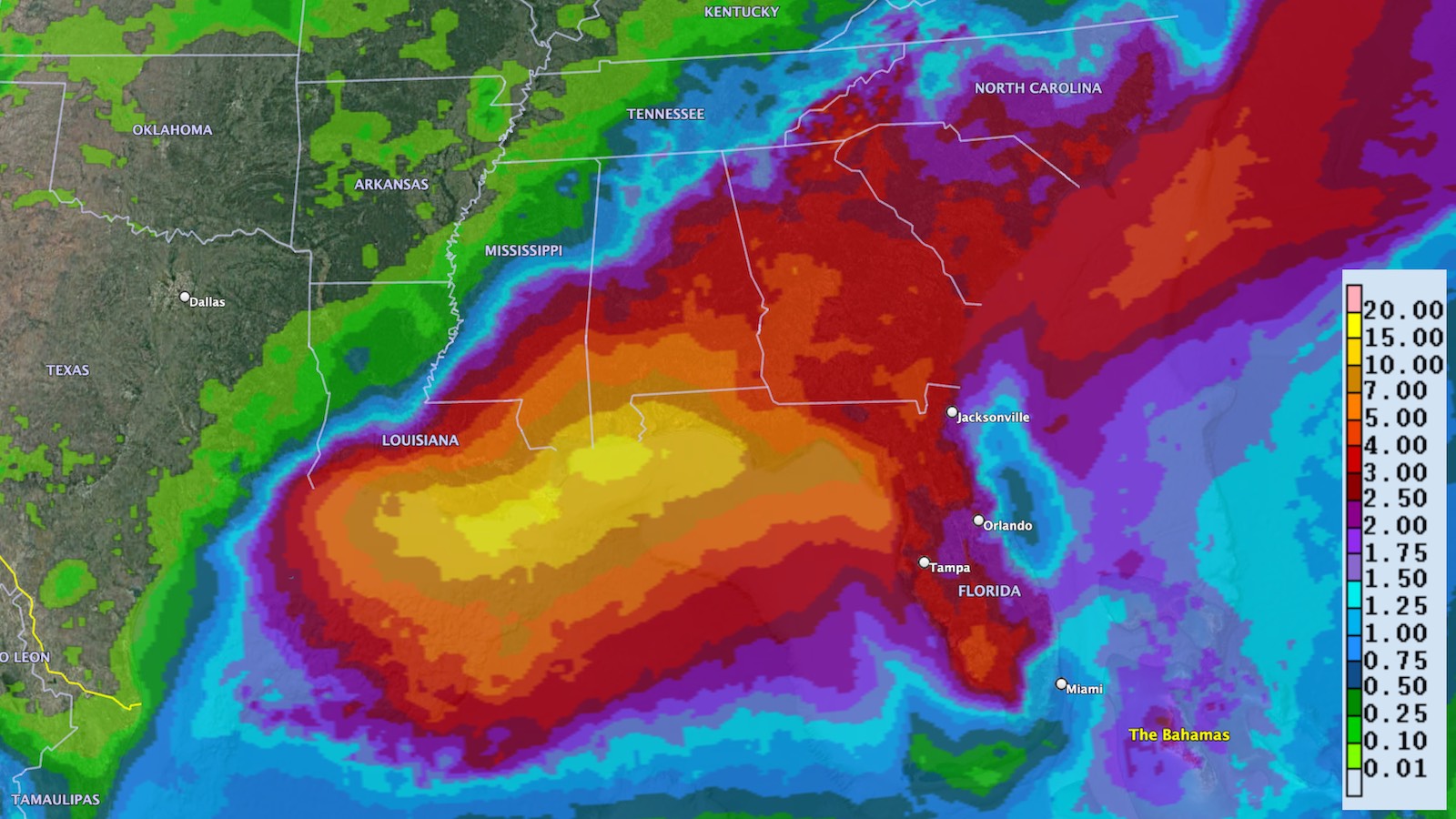

The NOAA/NWS Weather Prediction Center warned on Monday afternoon that rainfall totals could hit 15 to 20 inches over pockets of the central Gulf Coast from southeast Louisiana to western Florida. Most areas in this belt can expect at least 7-10″ of rain over the next week.

The stalled surface front, located just inland on Monday afternoon, was already generating heavy showers and thunderstorms (convection) across much of the region, with flash flood warnings up for parts of northern Florida. Just northwest of Tallahassee, a weather station near Lake Jackson measured 5.18” as of 6:42 p.m. EDT Monday. Going forward, hard-to-predict localized (mesoscale) weather features will help dictate where each day’s convection ends up within the overall envelope of concern.

Above the stalled front, an elongated weak upper-level low extends from the Southeast U.S. into the central Gulf of Mexico. This low will hold largely in place for the next few days, stuck in between strong upper-level high pressure producing record heat over the Southwest and Southern Plains (including an all-time high of 111°F in Huntsville, Texas, on Sunday) and the Bermuda High that typically holds court in midsummer over the western Atlantic.

While a midlatitude trough may try to pull the upper low out to sea by the weekend, another trough predicted to develop over the Bahamas and head northwest could essentially take its place. The upshot: upper level support is on the horizon to keep convection bubbling for days on end in and around the central and eastern Gulf Coast.

Wildly warm waters

Another cause for concern is sizzling sea surface temperatures (SSTs) across the northern Gulf. Widespread SSTs of 30-32°C (86-90°F) are 1-2°C (about 2-4°F) above average for this time of year. Given the stagnant features at the surface and aloft, it wouldn’t be out of the question for a tropical cyclone to evolve, especially if a circulation can become stacked just offshore. In its tropical weather discussion issued at 8 p.m. EDT Monday, the National Hurricane Center gave this setup a 10% chance of producing at least a tropical depression by Wednesday afternoon, and a 30% chance through Saturday.

Even if a tropical cyclone doesn’t form, this type of setup can give Gulf Coast residents understandable pause. As noted by tropical expert Michael Lowry, the only other time SSTs were this warm in the northern Gulf in early July was in 2016. Later that summer, an infamous rainmaking cyclone moved slowly westward from Florida to Louisiana, as evident in the tweeted satellite loop below (please note the date of Aug. 14, 2016!).

Despite lacking the closed warm-core circulation that would merit being named by NHC, this “no-name” low proved catastrophic for many thousands of residents, especially in the Baton Rouge area, where few residents carried flood insurance. Widespread rainfall totals of 20″ to 30″ were observed. According to one analysis, this collectively represented some three times more rain in Louisiana that was produced by 2005’s Hurricane Katrina. All told, the low caused an estimated 60 deaths and inflicted $10-15 billion in damage.

Diminutive Darby cranks up to Category 4 strength in the Eastern Pacific

Hurricane Darby bolted to Category 4 intensity in the open Eastern Pacific, about 1100 miles west-southwest of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, on Monday. Packing 140-mph winds as of 5 p.m. EDT Monday, Darby was the Western Hemisphere’s strongest hurricane of 2022 thus far. Even in the Northwest Pacific, only one of this year’s typhoons to date (Malakas) has been stronger than Darby.

From 5 p.m. EDT Sunday to Monday, Darby’s winds increased by a startling 65 knots (75 mph) in 24 hours. That’s more than twice the 30-knot increment needed to qualify as rapid intensification, based on the official NHC definition. One reason Darby was able to strengthen so quickly was its compact size. As of 5 p.m. EDT Monday, Darby’s eye was only 10 nautical miles wide (11.5 miles wide), and its hurricane-force winds extended only 11.5 miles in any direction. Smaller tropical cyclones can both strengthen and weaken more readily than large ones.

Darby’s path to rapid strengthening was also paved by light wind shear (under 10 knots), warm SSTs (27-28°C or 81-82°F), and a moist mid-level atmosphere (relative humidity around 70%).

Darby could intensify a touch more on Monday night, perhaps even approaching Category 5 strength. As Darby moves toward cooler waters, it should then gradually weaken until around Wednesday, when much stronger wind shear should put a quick end to the hurricane. Darby is predicted to be a post-tropical cyclone by Friday, well before it approaches Hawaii over the weekend.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.

Website visitors can comment on “Eye on the Storm” posts. Please read our Comments Policy prior to posting. Comments are generally open for 30 days from date posted. Sign up to receive email announcements of new postings here. Twitter: @DrJeffMasters and @bhensonweather