In what is shaping up to be one of the most dangerous flood threats of the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season, Potential Tropical Cyclone 22 was spreading torrential rains across the central and southwestern Caribbean on Friday afternoon. Of particular concern were the heavy rains occurring over southwestern Haiti, where deforestation in mountainous areas makes a highly vulnerable population at risk of deadly flash flooding.

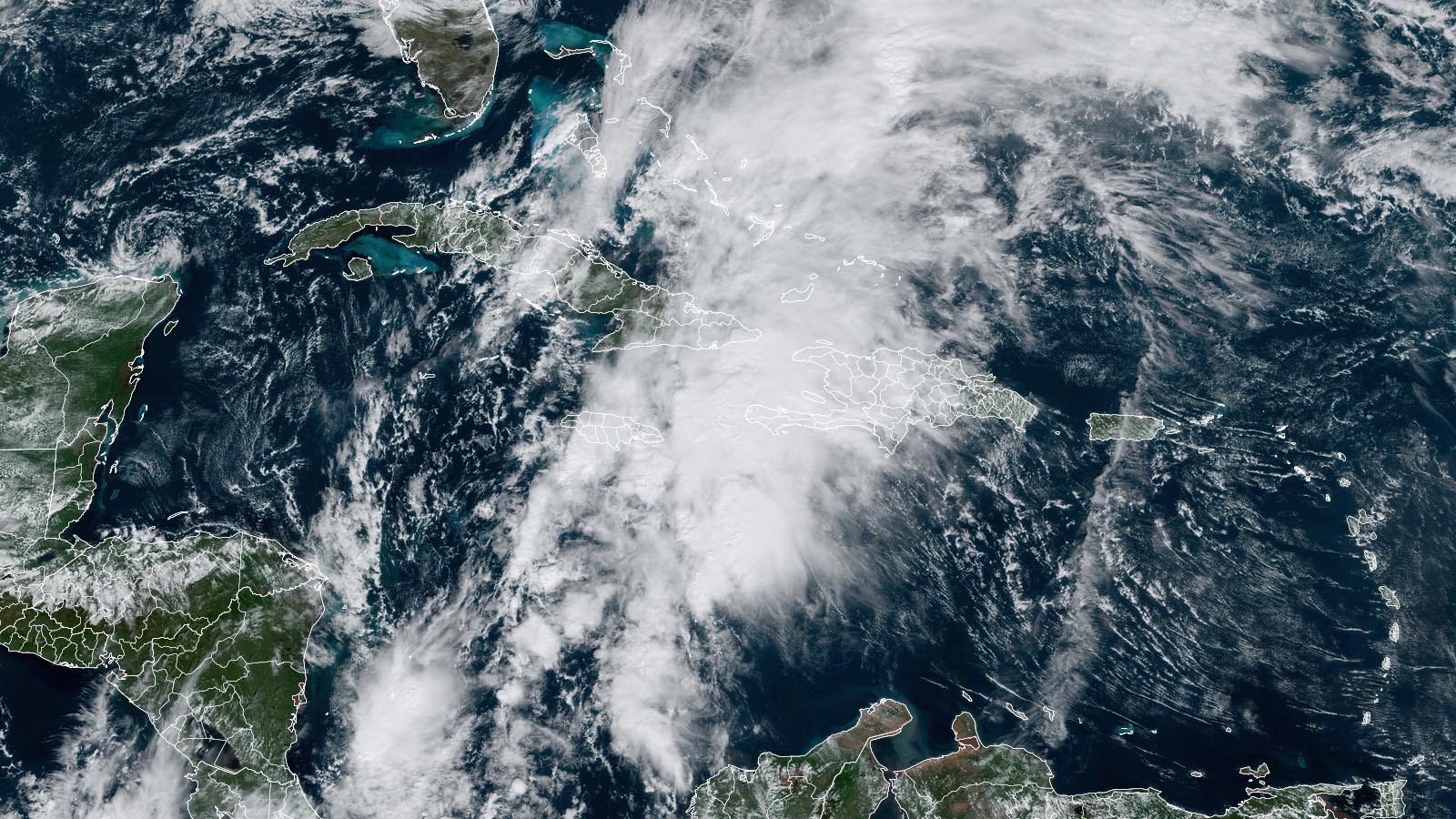

At 10 a.m. EST Friday, Potential Tropical Cyclone 22 (PTC 22) was centered about 155 miles west-southwest of Jamaica, headed northeast at 14 mph, with top sustained winds of 35 mph and a central pressure of 1004 mb. Satellite images showed that PTC 22 lacked a well-defined surface circulation, but was generating intense thunderstorms that were affecting Costa Rica, Panama, Jamaica, eastern Cuba, Haiti, the southeastern Bahamas, and the Turks and Caicos Islands.

Forecast for PTC 22

PTC 22 is suffering from high wind shear and intrusions of dry air, and the 10 a.m. EST advisory from the National Hurricane Center downgraded its chances of development into at least a tropical depression to 40% over the next two- and seven-day periods. Only slow development is expected, and the best chances for development appear to be on Sunday, after the system moves north of the Caribbean. Nevertheless, with PTC 22 expected to dump 4-8 inches of rain along its path, with isolated amounts of up to 16 inches, the potential for deadly flash flooding is high, particularly in southwestern Haiti.

The next name on this year’s Atlantic list is Vince. If PTC 22 becomes Tropical Storm Vince, then the Atlantic will have just one name left on the 2023 list: Whitney.

The 2023 Atlantic hurricane season has thus far seen a low death toll. Unofficially, three storms have been deadly thus far:

Hurricane Franklin: two direct deaths in the Dominican Republic

Hurricane Lee: three direct deaths in the U.S.

Hurricane Idalia: seven direct and three indirect deaths in the U.S.

Quick spin-up gives South Florida a tropical-storm-like hammering

Torrential rains of 8-13 inches and winds gusting above 50 mph slammed much of the populous corridor from Fort Lauderdale to Miami and the Florida Keys from late Tuesday to early Thursday, as a series of small-scale (mesoscale) lows associated with an extratropical storm strengthened dramatically just south of Miami.

The rain gauge malfunctioned at Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport during the storminess on Wednesday, as it did during an epic deluge in April. Even with the latest data gap, the airport had officially racked up 101.00 inches of rain for 2023 thru late Thursday, so it’s fast approaching Fort Lauderdale’s all-time record of 102.36” set in 1947.

Peak 48-hour rainfall totals through Thursday morning, November 16, included the following, compiled from various official and unofficial sources (see the full lists posted by the National Weather Service offices at Miami and Key West):

Monroe County: Key Largo, 13.80”

Broward County: Lauderdale-by-the-Sea, 13.31”

Miami-Dale County: Biscayne Park, 10.12”

Palm Beach County: Delray Beach, 6.19”

Collier County: Orangetree, 5.17”

Peak wind gusts, including marine stations and those just inland, included those below, again as compiled by the Miami and Key West offices. Sustained winds at airports are from hourly reports, so there were likely higher values in between those reports.

Carysford Marine Light: 87 mph

Government Cut (south end of Miami Beach): 75 mph

Port Everglades: 73 mph (67 mph sustained)

Dania Pier: 70 mph

Virginia Key: 57 mph (40 mph sustained)

Long Key: 56 mph

Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport: 55 mph (32 mph sustained)

Homestead Air Reserve Base: 55 mph (33 mph sustained)

Palm Beach International Airport: 56 mph (38 mph sustained)

The wild weather and surface low pressure developed on the east side of a non-tropical upper-level low moving across the Gulf of Mexico. Such a surface low linked to an upper low could be designated subtropical if it were to gain a coherent, sustained structure. In this case, radar imagery showed a sequence of spin-ups (mesolows) – similar to those that might develop within a large thunderstorm complex in the Midwest – rather than a sustained surface center. Interestingly, the phase-space classification tool from Florida State University (Figure 2), which draws on guidance from the GFS model, strongly suggested this complex would have symmetric warm-core characteristics (i.e., those associated with tropical storms and hurricanes).

This fast-evolving South Florida storm complex was not designated as a tropical or subtropical cyclone by the National Hurricane Center. On occasion, the center will “upgrade” a non-tropical system in subsequent analysis. This happened with a Northwest Atlantic system on January 16-17 that was belatedly recognized as a subtropical storm—meaning it would have been the first named storm of 2023 had it been tracked as a subtropical storm from the outset. Given the non-tropical aspects of this week’s system in South Florida, the odds of such an upgrade appear slim, but we’ll see if the center opts to carry out a posthumous analysis.

Source link