A disorganized tropical disturbance called Invest 97L is crossing the tropical Atlantic this week, but with only meager odds of becoming a named storm. That’s par for the course in the 2022 hurricane season thus far, which has been running against the grain of expectations in both the Atlantic and East Pacific.

As of 8 a.m. EDT Wednesday, August 10, Invest 97L was located in the deep tropical Atlantic, between latitudes 4 and 19 degrees north and near longitudes 32-33 degrees west, heading west at about 15 knots (18 mph). 97L is well within the Main Development Region (MDR), which straddles the tropical North Atlantic from the coast of Africa west through the Caribbean Sea.

August and September are peak season for the MDR, the period when so-called Cabo Verde waves like 97L are most likely to develop and head west across the region. Many of the worst hurricanes on record in the Caribbean, the Bahamas, and North America (including the U.S. Gulf and Atlantic coasts) originated as Cabo Verde waves.

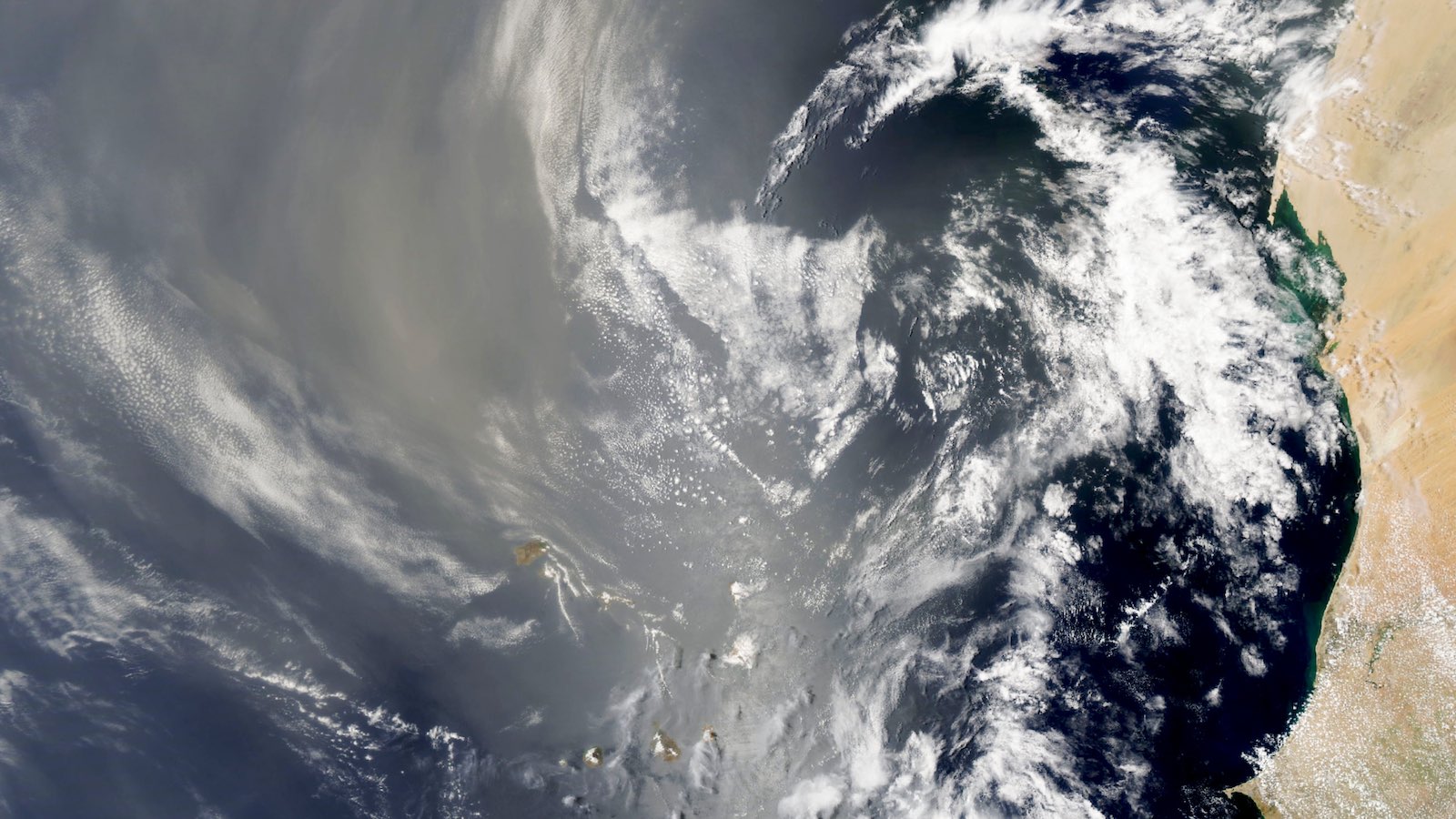

97L is unlikely to join that notorious group. The Saharan Air Layer (SAL) has prevailed across the MDR for weeks now, pushing vast quantities of storm-choking dry air across the Atlantic and reducing the instability needed to fuel the showers and thunderstorms (convection) that spiral around and into tropical cyclones.

Thus far, 97L has stayed just south of the SAL, giving it access to a lifeline of modestly favorable conditions. The disturbance is embedded in a moist mid-level atmosphere (relative humidity around 70 percent) amid light wind shear (less than 10 knots) atop warm sea surface temperatures (SSTs) of around 28 degrees Celsius (82 degrees Fahrenheit). Even with these pluses, 97L has struggled to organize, ginning up only sparse pockets of convection and failing to carve out a low-level circulation.

By late this week, 97L will be angling west-northwest into an environment of high wind shear and drier air. Strong upper-level southwest flow is expected to steer any development of 97L well east of major land areas. In its Tropical Weather Discussion issued at 8 a.m. Wednesday, the National Hurricane Center gave 97L a 20% chance of development through Friday, August 12, and a 30% chance through Monday, August 15.

The head-scratching early season of 2022

At first glance, the Atlantic hasn’t been all that quiet. On average, for the period 1991-2020, the fourth named storm doesn’t arrive until August 13, and the first hurricane doesn’t form until August 11. By those standards, with three named storms but no hurricanes as of August 10, the Atlantic season is just now starting to slip behind climatology.

However, none of this year’s three Atlantic storms packed much punch. That’s especially true of Colin, which spent its entire 24-hour life as a minimal tropical storm near and just inland from the coast of South and North Carolina.

Prior to Colin, tropical storms Alex and Bonnie each developed after unusually long periods as potential tropical cyclones (56 and 88 hours respectively). The disturbance that eventually gave birth to Alex dumped torrential rains in Cuba, taking four lives, and drenching South Florida.

Only one of this year’s three named Atlantic systems through August 9 – Bonnie – developed from an MDR wave. And Bonnie was a disorganized, unnamed system for days, until just 15 hours before it came ashore in Nicaragua.

As of August 9, the Atlantic had mustered only 3.25 named storm days (the total span of time with at least one named storm in progress), compared to an average at this point of 10.8, according to the Real-Time Tropical Cyclone Activity page curated by Colorado State University (CSU).

The Atlantic season has been equally tepid by the yardstick of accumulated cyclone energy, or ACE – a cumulative measure of the duration and wind speed of a season’s tropical cyclones, but not their size. This year’s Atlantic ACE so far has been 2.8 units: That contrasts with a year-to-date average of 12.3.

Meanwhile, in the East Pacific …

It’s a telling thing that Bonnie hit its apex only after it crossed Central America and moved into the East Pacific (where it kept the name Bonnie, since it remained an identifiable tropical cyclone while over land). After having simmered for days in the Caribbean, Bonnie leapt to Category 3 intensity as it moved south of Mexico, packing 115-mph sustained winds.

Bonnie was no fluke. Through August 9, the East Pacific had generated eight named storms, seven hurricanes, and two intense hurricanes, compared to 1991-2020 averages to date of 7.2, 3.7, and 2.0. Named storm days and hurricane days are both more than 50% above the year-to-date averages, and the East Pacific ACE for the season thus far is 79.6, compared to an average of 52.9.

Why so active? Persistent circulation patterns have favored cyclonic low-level flow over the far northeast Pacific around latitudes 10 to 15 north – prime territory for tropical cyclone development – and the cool waters of La Niña have stayed south of this area. Moreover, CSU’s Phil Klotzbach observes that East Pacific storms have taken advantage of periods of upward motion associated with strong Kelvin waves (sprawling, slow-moving tropical impulses that travel the equator from west to east).

Why is this happening, and what’s next?

Experts are furrowing their brows over the unexpected turn of events in the Atlantic and East Pacific. Based in large part on expectations (now confirmed) that La Niña would prevail for a third consecutive autumn, the pre-season May outlooks issued by NOAA laid 65% odds for an above-average season in the Atlantic and 60% odds for a below-average season in the East Pacific.

La Niña has done its part: the Niño 3.4 index has dipped to the threshold of moderate La Niña status this week, according to NOAA, and odds are now high that a robust La Niña will continue into autumn. But tropical cyclones haven’t yet responded as expected.

So what’s going on? It’s still early in the Atlantic season, of course, so it would be premature to predict a quiet year. As discussed last week, several major seasonal forecasting groups trimmed their numbers just slightly in their August updates. Yet there remains strong consensus on a busier-than-usual Atlantic season.

In his Substack blog Eye on the Tropics, meteorological Michael Lowry points out that 90 percent of the ACE in a typical Atlantic season occurs after August 10: “…years like 2019, 1999, and 1998 recorded similarly low tropical activity early on, but ended the year above average, in some cases flipping the switch to hyperactive hurricane seasons.”

By late August, the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) and a convectively coupled Kelvin wave (CCKW) could align in a configuration that would favor upward motion and tropical cyclone development in the Atlantic.

SSTs in the Main Development Region have cooled a touch in recent weeks, and the warmth is concentrated toward the southern part of the MDR. This arrangement may have put a modest damper on the start of Cabo Verde season. Another factor has been more-stable-than-usual air over the MDR, as noted by Lowry.

Further west, the prolonged spin-up times for both Alex and Bonnie showed how seemingly favorable conditions in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean weren’t quite enough for those early systems to organize quickly.

As for the East Pacific, it was a highly productive nursery for tropical cyclones from 2014 to 2019, then hewed near or slightly below average during the La Niña years of 2020 and 2021. Seasonal forecasters at the NHC and NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center have noted the tendency of active multi-year periods such as 2014-2019 in the East Pacific to persist, keying off large-scale SST patterns that can transcend individual El Niño and La Niña events.

The one place where La Niña’s connection to tropical cyclones has played out in traditional fashion this year is over the Northwest Pacific. There, it’s been an exceptionally quiet typhoon season so far, with only four named storms and two typhoons compared to year-to-date 1991-2020 averages of 10.0 and 5.4. The Northwest Pacific’s seasonal ACE thus far of 22.4 is far short of the year-to-date average of 89.8.

Forecasters at TropicalStormRisk.com called for a relatively quiet Northwest Pacific season in May based on La Niña expectations. They doubled down in their August 9 update, now predicting a seasonal ACE of 166 compared to the 1991-2020 average of 301.

“La Niña conditions are linked to stronger than average trade winds over the NW Pacific basin, which results in reduced cyclonic vorticity and less favourable conditions for storms to develop and intensify,” the forecast group noted.

The hemispheric picture

All told – including the Atlantic, Northeast and Northwest Pacific, and North Indian basins – the Northern Hemisphere had spun up a season-to-date ACE of 110.3 units as of August 9. That puts the year so far among the quietest 25-30% of all seasons to date, based on data compiled by Colorado State University (CSU) going back to 1970, when reliable satellite records begin for the East Pacific.

The CSU database shows that 14 out of 53 seasons had accumulated at least 110 units of ACE across the Northern Hemisphere by August 9.

Given the travail being produced this summer across the Northern Hemisphere in the form of record-melting heat waves, punishing drought, and deadly flash floods – with much of the havoc related to human-caused climate change – we can be grateful that tropical cyclones haven’t piled on, at least not yet. Apart from Tropical Storm Meghi, which took 214 lives across the Philippines in April, the landfalling tropical cyclones of 2022 thus far across the entire Northern Hemisphere have led to a relatively small total of 45 deaths.

Heading into the teeth of hurricane and typhoon season, it’ll take a lot of luck, and serious preparation and awareness, to keep those numbers down.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post. Our thanks to Phil Klotzbach at CSU for real-time and historical tropical cyclone data. Website visitors can comment on “Eye on the Storm” posts (see comments policy below). Sign up to receive notices of new postings here.