The federal government’s eighth State of High Tide Flooding report is its starkest assessment yet detailing the upward trends of rising seas spilling into coastal cities.

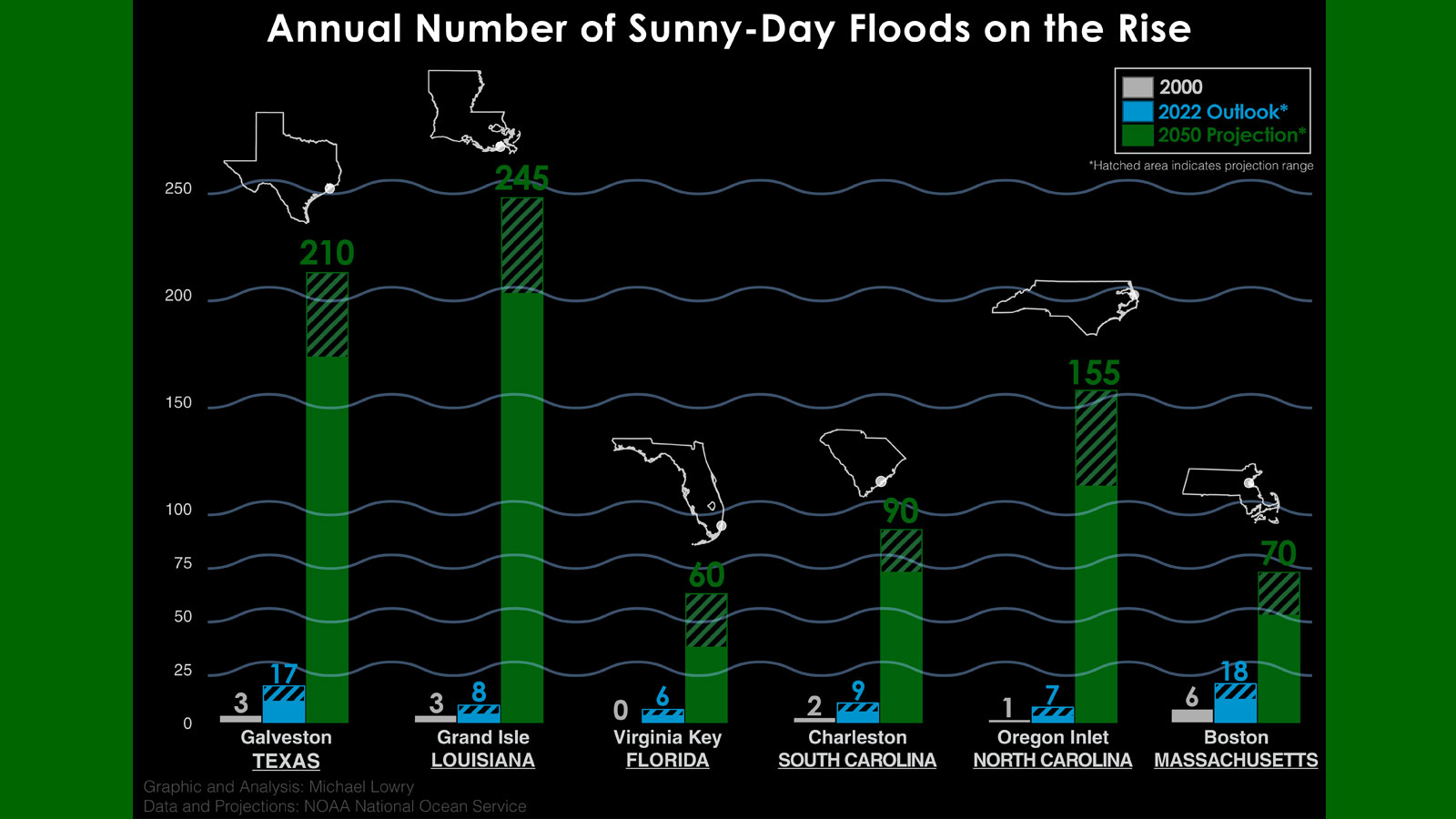

Scientists at NOAA’s National Ocean Service – the agency’s water counterpart to the National Weather Service – earlier this month reported threefold and fivefold increases since 2000 in sunny-day, high-tide flooding for the southeastern U.S. and western Gulf Coast, respectively. Despite an ongoing La Niña in the eastern Pacific, which can temporarily dampen sea levels along the U.S. coast, the frequency of relentless saltwater flooding – unrelated to extreme weather – has continued to accelerate across the U.S. in 2022.

The report underscores an alarming growth of chronic sunny-day floods at nearly 100 tidal locations monitored by NOAA along the U.S. coastline, taxing the ability of modern infrastructure to adapt by gradualism to contain increasingly disruptive and destructive high tides. The latest outlook predicts sunny-day flooding – occurring now about once every other month at any given spot, averaged nationwide – to become as commonplace as every other day by the end of traditional 30-year mortgages originating today.

Sea-level rise driven by warming climate

Several factors affect differences in local sea-level rise, including sinking land and a slowing of the Gulf Stream current along the eastern seaboard, especially along the southern extension of the Gulf Stream known as the Florida Current.

But even in places like South Florida, prone to both subsidence and fluctuations in the nearby Florida Current, government scientists estimate the vast majority – roughly 8 cm of the 11 cm rise over the past 20 years – are driven by warmer oceans and melting land ice from global climate change. The octopus in the parking garage may be the modern-day canary in the coal mine for rising seas, with marine life swept in with advancing tides and bubbling up through porous bedrock beneath.

The latest report complements a sweeping NOAA Task Force report released last February updating sea-level projections for the U.S. coastline from climate change scenarios outlined in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report released last summer. These new updates, the first since 2017, increase scientific confidence into the next century of deleterious consequences to U.S. coastal communities and ecosystems unless comprehensive mitigation measures are taken.

Rising seas and coastal populations … and future storm surges

The U.S. population seeking a permanent place along the coasts is booming. Nearly 40 % of the nation’s 330-plus million live in a coastal shoreline county on land comprising less than 10% of the total U.S. land area, excluding Alaska. In many hurricane- and storm surge-prone areas along the gently sloping Gulf Coast, population and attendant wealth have skyrocketed. In Collier County on Florida’s southwest coast, home to Naples and one of the country’s most prosperous communities, population has soared by nearly 1000% over the past 50 years. An estimated 40% of Florida’s population is at risk of storm surge flooding, with the highest concentration of per capita losses from storm surge along Florida’s southwestern shoreline.

Similar to lowering the rim of a basketball goal (or alternatively raising the floor under the basket), rising seas will lower the bar for future storm surge “dunks,” worsening extreme flooding, even if the characteristics of storms don’t change. Recent studies conclude damage from storm surges and sea-level rise under a moderate global warming scenario could top $1 trillion by the end of the century in the U.S. – most egregiously on the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. Under an extreme global warming scenario, these damages could top $14 trillion worldwide without appropriate adaptation measures to reduce risk.

Added to the tidal wave of coastal concerns are compounding issues of climate change, which may hasten the destructive feedback loop.

Those most at risk – higher coastal populations and traditionally under-served populations

As government scientists noted in their annual high-tide flood report, cooler than average waters around the equator in the eastern Pacific – a phenomenon coined La Niña – have reduced otherwise higher seas, particularly on the U.S. west coast. This very persistent La Niña, in its third successive year and only the third triple-dip in the 73-year record, has been a deceptive windfall for chronic coastal flooding in recent years. Because of the warming climate, however, El Niño events – the warming of the eastern Pacific which can exacerbate sea levels along both the east and west coasts – and not La Niña events are expected to eventually become more common later this century, though this issue remains an active area of research.

Meanwhile, scientists are finding higher rates of rainfall in tropical cyclones, especially near their centers where winds are strongest. In a paper published earlier this year in the journal Nature, Princeton University and MIT scientists examined the combined impacts of worsening storm surges from rising seas and increasing rainfall in tropical cyclones. The authors found an increase in the incidence of extreme flood events from tropical cyclones – by as much as 36-fold in the southern U.S. and 195-fold in the northeastern U.S. by the end of the century.

Disadvantaged populations – as so often – hardest hit

Economically disadvantaged populations and communities of color are expected to be disproportionately at risk of coastal flooding from sea-level rise in the years ahead. A 2021 study in the Journal of Climate Change and Health found that in the next three decades across North and South Carolina, sea-level rise may increase low-lying flooding by as much as 700 percent in lower- income Black communities compared to higher-income white communities. These findings are consistent with extensive peer-reviewed research showing a higher risk from natural disasters to low-income households, under-resourced communities, and communities of color.

In recent years, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, FEMA, has explicitly prioritized the needs of historically underserved communities. The agency in early August announced an infusion of $3 billion into federal flood mitigation and resilient infrastructure programs targeting communities most at risk.

Sea-level rise remains one of the most conspicuous and consequential stains of global warming. Its effects are wide-reaching and pervasive, and overlooking the rising tide amounts to refuting the calling card of a changing climate. Some changes are less perceptible, but in cities from Galveston to New Orleans, Miami to Charleston, Norfolk to Boston, and in hamlets between, the fingerprints of accelerating seas are unmistakable. And the costs – both ecologically and economically – have never been higher … and are expected only to increase.

Michael Lowry is Hurricane Specialist and Storm Surge Expert at WPLG, the ABC affiliate in Miami, Florida. He is a former emergency management official with FEMA and senior scientist at the National Hurricane Center.

Source link