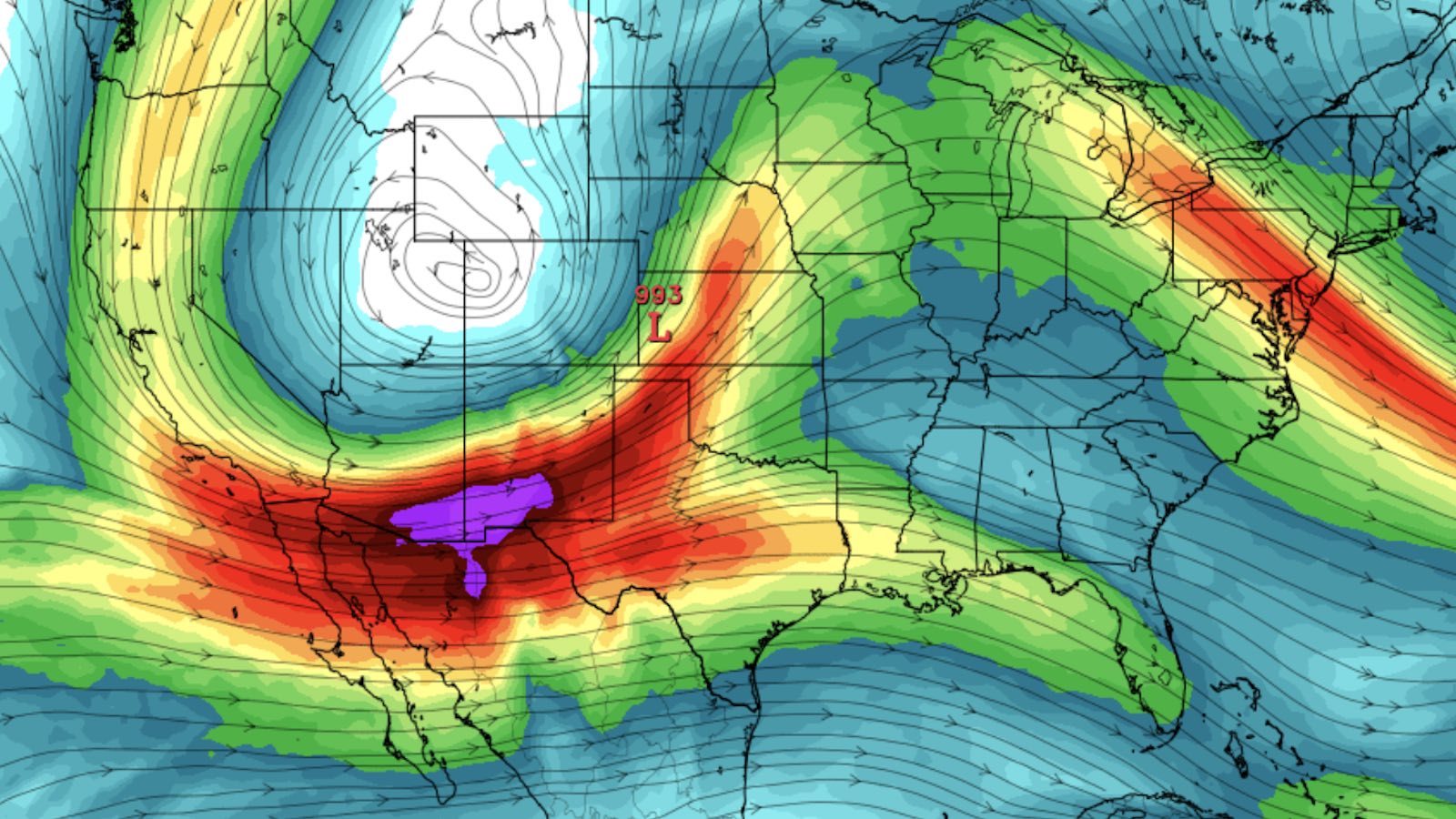

A rash of tornadoes and other severe weather appears increasingly likely to erupt from Texas to the Mississippi Valley early in the week of December 12-16. As an unusually strong upper-level storm approaches, plenty of mild, moist air is expected to be in place to fuel severe thunderstorms.

The same upper-level storm could help bring much-needed moisture to parts of California and the Southwest.

No month of the year is immune to U.S. severe weather – especially in the south – but the factors expected to come into play next week will be unusually potent for December. Multiple forecast models have become increasingly emphatic about the imminent threat.

On Thursday, December 8, the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center outlined risk areas for severe weather valid on Day 5 (Monday, December 12) and Day 6 (Tuesday, December 13). The Day 6 outlook includes the equivalent of an enhanced risk – which is the highest tier allowed in SPC outlooks beyond Day 3.

According to SPC’s Elizabeth Leitman, such a strong Day 5 outlook has been issued only five times in the nine years of probabilistic outlooks for that time range. The other four examples were all issued in April, not in December!

In contrast, the two record-smashing severe events that closed out 2021 were not flagged at all in SPC risk areas until Day 3. These included the deadliest December tornadoes on record, which killed at least 89 people in and around western Kentucky on December 10-11, and the most widespread December tornadoes on record, a derecho-driven swarm of 120 twisters that swept across the central and northern Plains as far north as Minnesota on December 15.

Forecast confidence in an upcoming event is not necessarily a sign of how strong that event will be, but the two tend to be highly correlated.

Both the ECMWF and GFS model have consistently shown that vertical wind structures favoring formation of tornadic supercell thunderstorms—including winds that strengthen and veer with height—will sweep across the Southern Plains and toward the Southeast from late Monday into Wednesday, December 12-14.

Meanwhile, rich low-level moisture and unusually warm surface air are already in place from Texas to the Southeast. Even with weak frontal surges over the next few days, this muggy air mass should surge back northward well before the upper-level storm and its associated surface fronts move into place.

Among the biggest hazards with tornadoes in December are the long hours of darkness. A potential set-up as strong as next week’s carries with it the chance of tornadic storms raging well after sunset, as was the case in the December 10-11 outbreak last year. Nighttime tornadoes are notoriously dangerous, not only because they’re much harder to see but also because finding shelter can also be more difficult.

Atlantic’s vigorous low-latitude system not expected to become a named storm

A powerful area of low-pressure gathering strength along a frontal system over the remote subtropical Atlantic, discussed in a post at this site on December 6, now appears unlikely to be designated a tropical or subtropical storm by the NOAA/NWS National Hurricane Center.

In a special outlook issued at 8:40 a.m. EST Thursday, NHC gave only 10% odds that the system would become a tropical or subtropical cyclone. Despite a large field of winds exceeding tropical-storm strength, the system is now embedded in a strong low-latitude jet stream, which will quickly eliminate its chances of becoming tropical in structure and soon quash any subtropical component. In addition, the storm is now accelerating northeast over waters much cooler than 26 degrees Celsius (79 degrees Fahrenheit), the rule-of-thumb minimum temperature for tropical development.

Regardless of how it’s classified, this storm is a mammoth wave-producer and will continue to stir up the North Atlantic into the weekend as it churns northeast, passing just west of the Azores islands by Saturday. After it becomes enmeshed in an approaching mid-latitude storm, the complex may slam into western Europe next week.

El Niño on verge of becoming likely next year

If the latest seasonal outlooks prove correct, the La Niña conditions that have held sway almost continuously since mid-2020 will soon be a memory. The monthly El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) outlook issued on December 8 calls for La Niña to prevail through northern winter 2022-23. However, this outlook should give way to increasing odds of El Niño by next summer and fall, as sea surface temperatures rise across the eastern equatorial Pacific into at least the neutral range – an outcome now predicted by the vast bulk of long-range forecast models consulted by NOAA.

There’s no precedent of La Niña’s returning for a fourth consecutive northern winter in NOAA data extending back to 1950, nor in an alternative Ensemble Oceanic Niño Index from meteorologist Eric Webb that goes back to 1850.

With all this in mind, fall 2023 may be ruled by El Niño rather than by neutral conditions or La Niña. If so, that would help tamp down on hurricane risk in the Atlantic. It could also help diminish the drought conditions that have intensified over the last couple of years in large parts of the Southwest and Southern Plains.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post. Website visitors can comment on “Eye on the Storm” posts (see comments policy below). Sign up to receive notices of new postings here.