GLASGOW, SCOTLAND – This past November my hometown of Glasgow played host to the United Nations COP26 climate change conference. For two weeks the city was taken over: suited delegates hurried through the Glasgow subway system; armed police blocked roads; sculptures appeared on derelict land; welcome banners hung on churches, temples and gurdwaras. During this time, I attended the official U.N. and U.K. government-run spaces and took part in many side events arranged by research bodies, campaigns, and arts organizations.

Toward what end? To learn more about the roles the arts play during the conference. Part of my work at Creative Carbon Scotland, an environmental arts charity, focuses on a publicly available online resource called the Library of Creative Sustainability, which documents collaborations involving artists to achieve environmental sustainability goals. There’s no doubt that the arts do have an important role to play in addressing climate change, but what form might this take in the unique context of COP? I’ll try to share some key learnings.

Strengths artists bring to the climate challenge

Why, some might ask, should the arts be involved in tackling climate change? Well, the current state of climate emergency is increasingly recognized as being a cultural issue and also a technical, scientific, and infrastructural one. We don’t need just to develop and deploy new technologies: There’s also a need to find fundamentally new ways of thinking, imagining, and living, not just as individuals but collectively. Organizations like Climate Outreach illustrate that need, showing that providing people research findings is not sufficient to encourage action, and that creative approaches also are needed to help fill this gap. Author Amitav Ghosh has described the climate crisis as a “crisis of culture and therefore of the imagination.”

Artist Frances Whitehead explores this issue in her article “What do Artists Know?”, highlighting skills that creative practitioners possess, which can be immensely useful to those working on climate change. Artists are trained to find new ways of thinking and understanding issues. They are skilled and versatile collaborators and communicators. They use visual, sonic, kinaesthetic, and narrative methods that offer alternative lenses for understanding.

Creative Carbon Scotland’s Library of Creative Sustainability documents projects makinga good use of these skills. Many of the examples involve long-term and deep collaborations in which artists and environmentalists work together over an extended period, learning from each other and developing innovative solutions to seemingly intractable problems.

In some ways, the situation around summits like COP26 can feel like the exact opposite: A two-week circus comes to town and then abruptly disappears. How could collaborations between the arts and environmentalism respond effectively to this unusual situation?

Conference cultures and venues yearn for a touch of creativity

Leading up to COP26, I was in touch with Hannah Entwisle Chapuisat, co-founder and curator of the Switzerland-based organization DISPLACEMENT: Uncertain Journeys, as we co-authored a new article for the library. DISPLACEMENT brings artistic interventions into intergovernmental policy conferences, seeking to improve international policies supporting people displaced by natural disasters and the effects of global warming. It brings artistic work into the often dry and formal spaces of international conferences to re-engage policymakers with the human realities of their scientific and policy work and to encourage more effective and ambitious action.

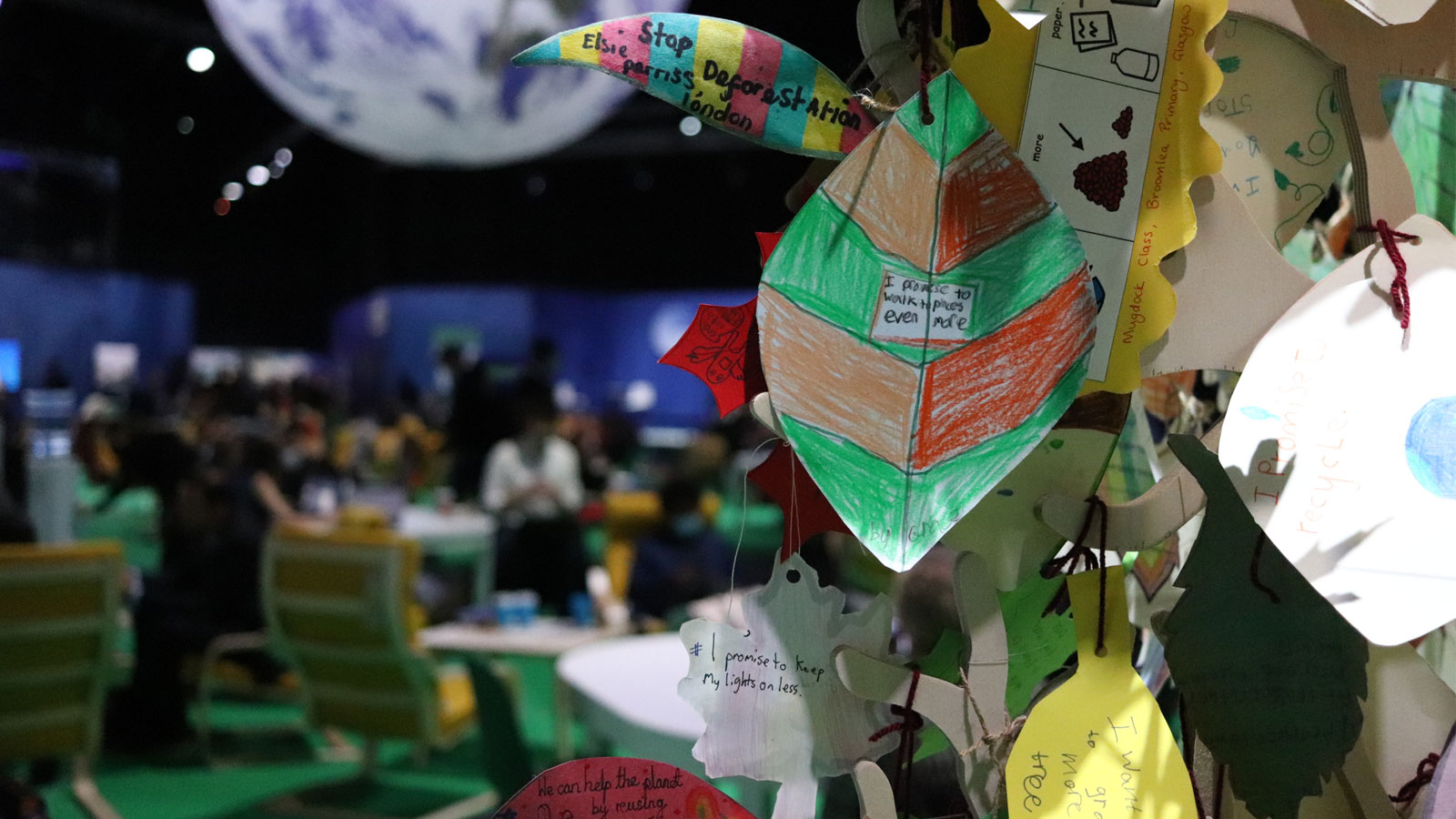

Exploring the official COP26 venue brings to mind Hannah’s description of policy conferences as places in need of creative intervention. The space, largely windowless, felt cut off from the outside world. There were artistic contributions including sculptures, photos and cartoons around the building, but they were largely relegated to spaces like corridors and foyers. In contrast, the most effective uses of art were in collaborative contexts not relegated to a separate space.

For example, an event at the Peatland Pavillion featured storytelling, a new artistic film, and a bag of peat to stick a hand into. It made me feel fully engaged for the first time all day. This feeling was consistent with Hannah’s own experiences from DISPLACEMENT: She found that many of their most effective artistic interventions were participatory. Artist Lucy Orta, for instance, distributed an “Antarctica World Passport” to delegates. Artists Lena Dobrowolska and Teo Ormand-Skeaping engaged official COP26 delegates in direct discussions.

Also present at COP26 was Jonathan Colin from Chocó, Colombia-based organization Más Arte Más Acción (More Art More Action, MAMA for short). MAMA specialises in collaborative environmental justice projects among artists, academics, researchers, activists, and thinkers, focusing on their local context in Chocó and on international connections. Its approach to COP26, in contrast with that of DISPLACEMENT, involved working outside of official spaces and with Indigenous leaders, artists, local activists, and others under-represented in official spaces.

Since 2019, MAMA has been working on the project Diálogos Posibles (Possible Dialogues) with the Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the Colombian Amazon (OPIAC). MAMA and the OPIAC produced three films in Colombian Indigenous territories in 2021 exploring Indigenous peoples’ struggles in relation to climate change and justice.

These films were screened locally within the territories but also used to amplify their messages internationally. They were screened at cultural venues in Glasgow during COP26 and used as the basis for discussions on climate justice and future climate action. The emphasis at COP was not on influencing the results of the conference itself, but rather on education and on developing movements from the ground up.

The same applied to many of the most striking artistic interventions around COP26, few of which sought to influence policymakers at the conference but tended to work with local groups and visiting campaigners to develop understanding, create new connections, and build more lasting movements.

Lessons learned, and the critical need for collaboration

Despite clear differences between working with policymakers and grassroots activists, there are key lessons to be learned from both DISPLACEMENT and MAMA.

The first is that the arts can open meaningful spaces for discussion, allowing people to think in new and different ways. Both organizations use artistic methods to break out of every-day thinking and create a sense of personal connection to climate impacts occurring at great distances.

Secondly, they both use art along with other approaches in a collaborative way, with artists working to connect groups and communities. DISPLACEMENT tries to help policymakers better understand the needs of people on the frontlines of climate change; MAMA tries to empower frontline communities to reach and influence policymakers.

For both organizations, collaboration is critical. To be able to use artistic methods to further environmental goals, artists and environmentalists must develop a deep understanding of each other’s values, skills, goals, and beliefs. To do so, they must work together over an extended period to get to know each other, a time-consuming process that nevertheless leads to long-term benefits, and to the ability to capitalize on brief moments like those provided by the COP26 summit.

Now that COP26 is in the past, preserving momentum is essential, progressing from short-term artistic interventions made around COP26 to long-term collaborations that build change in more lasting ways. Resources like the Library of Creative Sustainability seek to show how these collaborations can work effectively.

Activities around COP26 demonstrated how alive the arts communities are to the role they can take in addressing climate change. But it’s by working with others beyond the arts that they can make the greatest difference, whether in the context of a convention or on the streets.

Lewis Coenen-Rowe is culture/SHIFT Officer at Creative Carbon Scotland, where he runs the Library of Creative Sustainability.

Source link