One major flood can bring an entire community to its knees. Three devastating floods in three years is almost unfathomable, but that’s what some parts of Houston went through between the Memorial Day flood of May 2015, the Tax Day flood of April 2016, and the mind-numbing Hurricane Harvey floods of August 2017. Harvey dumped more rain on the contiguous United States than any other hurricane on record.

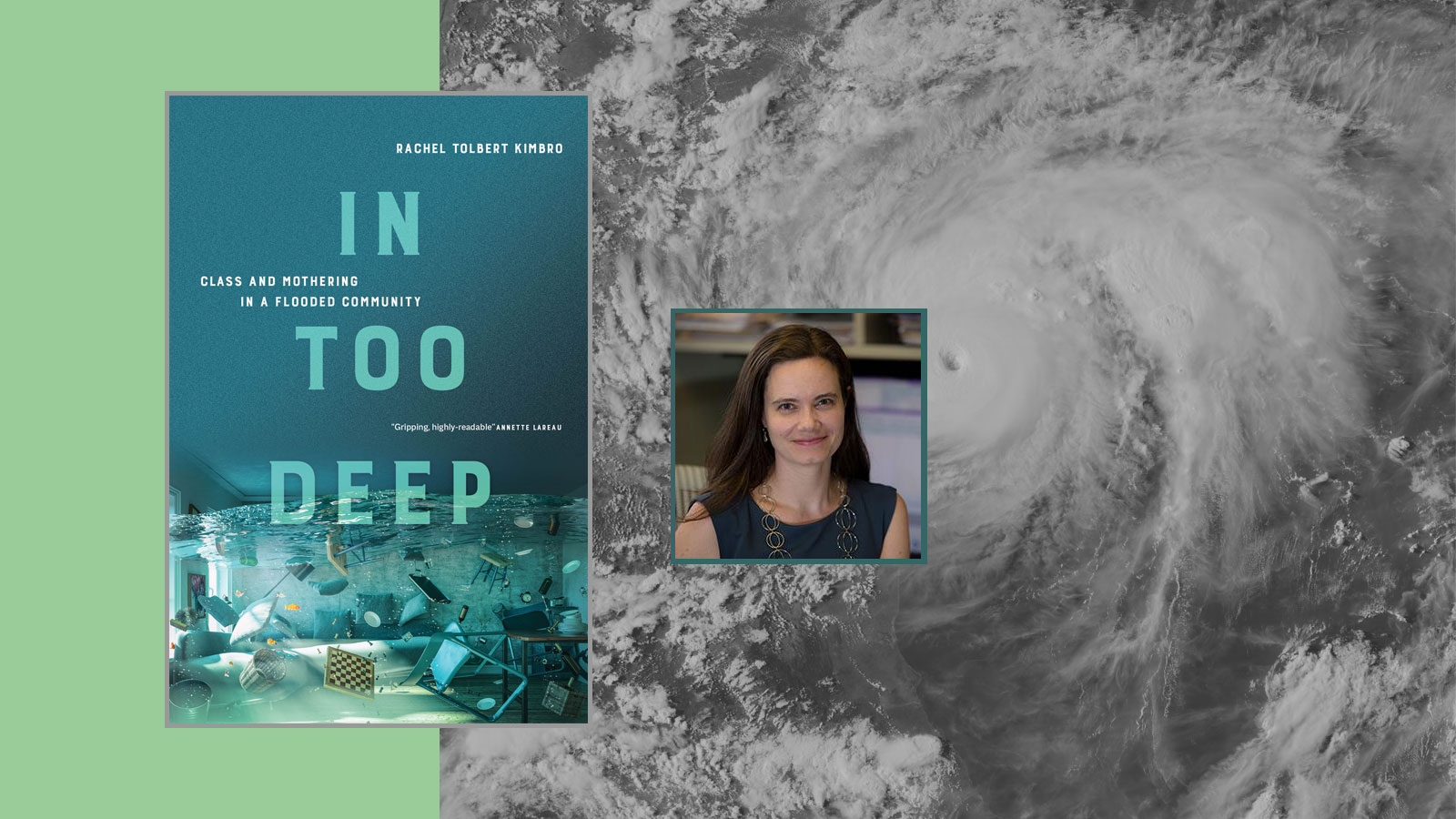

Sociologist Rachel Kimbro, dean of the School of Social Sciences at Rice University, was inspired by the local sequence of flood disasters to analyze one especially hard-hit yet distinctive neighborhood. Identified by the pseudonym Bayou Oaks, it’s the venue of a multiyear study summarized in Kimbro’s new book, In Too Deep: Class and Mothering in a Flooded Community.

As Kimbro stresses, Bayou Oaks is by no means the most vulnerable neighborhood in Houston. Yet she found that a litany of challenges – many of them specific to gender – faced even these well-resourced mothers. Their “curated” approach to choosing a neighborhood and raising a family also intensified their ties to a location that is highly flood-vulnerable, nestled within a huge and complex city.

Kimbro shared her thoughts on the study and the lessons it offers for managing families and floodscapes in a conversation with this YCC regular contributor. The interview below has been condensed and lightly edited.

Bob Henson: Your plan for this study came together remarkably quickly after Harvey.

Rachel Kimbro: It’s hard to describe it as anything other than a bolt of lightning. I needed to tell the story of this neighborhood, these women and these families. I really felt they were living on the front lines of climate change. I wanted to show what that experience was like, down to the nitty-gritty detail, in hopes of illuminating the experience and making it a cautionary tale for policy makers.

Henson: Were there any particular inspirations for the study and book in terms of how you approached it?

Kimbro: Definitely Children of Katrina by Alice Fothergill and Lori Peek, and Alice Fothergill’s book Heads above Water about a flood in Grand Forks, North Dakota.

Both of them [cover] how this experience impacts families. I’d definitely been inspired by their work and then wanted to bring it to this case of repetitive flooding. Three times in three years seems like a really unique case.

Henson: Tell us about the neighborhood and what it looked like right after the Harvey flood.

Kimbro: The lots are very large. The homes range from modest three bedrooms to large five bedrooms. There’s a lot – or should I say, there were a lot – of midcentury-modern homes in the area that were really beautiful. Huge live oaks are everywhere.

Immediately after the flood, you’d have to navigate streets with these 8- to 10-foot piles of debris outside of everyone’s homes. And because so many homes across Houston flooded after Harvey, it took the city a really long time to pick up all the debris. So in some cases it was months before these belongings disappeared. It smelled terrible, too.

Henson: I was struck by the calibration these mothers used to assess risk – how they talked about the “bad floods” of 2015 and 2016 as benchmarks for how Harvey might behave. What did they learn from that benchmarking experience? And what can others learn from it, given that we’re in this nonstationary climate?

Kimbro: Other social science work has shown that that is how humans assess risk – looking at past events to use to predict for the future. [Some of the mothers] would lift their furniture to the precise level of the last flood, an inch or two above that.

What was really interesting to me was when I asked them, “Do you think you’re going to flood again?” Those who flooded for the first time during Harvey all said that they didn’t think they would flood again, even after what the neighborhood had gone through. The women who had [been] flooded more than once used that to alter their future risk perception – “Well, it happened to me twice, so yes, it probably can happen again.”

Henson: You found that mothers tended to lead the way in dealing with the Harvey flood, both in preparation and in recovery. So often we see images of men boarding up buildings, men rescuing people. It seems as if our mental pictures of disaster response and recovery are “men at work.” But often it’s women at work, and unpaid work at that.

Kimbro: Women’s work before, during, and after disaster is often unsung, but really they are the ones holding the community together. The men may be doing more visible work, usually external to the home, but the women are doing a whole lot internally. It’s not just the physical labor of moving furniture and belongings up to higher places in the home. It’s also preparing the children for what is going to happen, putting together some crafts that you could do when the power is out, and also trying to emotionally prepare the family for the loss of the home. That’s really a lot of labor.

Henson: You stressed across the book that these women benefited from their status as upper-middle-class mothers and had all kinds of resources at hand, but you also described the physical labor of digging through the muck: Everyone had to do that. You also described vividly how needing to accept help was a leveling thing, and not always easy for some of the mothers.

Kimbro: I thought it was really interesting how the mothers drew distinctions around the type of help that was or was not acceptable. They were by and large willing to accept the physical help – taking things out of their home and putting them on the curb – although they did see it as a violation of privacy. That was a little difficult for them.

In terms of financial support, each mother had a slightly different calibration of what was okay and not, based on her own family circumstances. They felt like some people were taking advantage when they had flood insurance and in theory should have had the resources they needed to rebuild. In particular, there was a lot of discussion about whether it was okay to use GoFundMe.

Henson: The various forms of labor taken on by the women in your study seemed to multiply after the flood. Do you see any parallels between the increase in class inequity that often happens after a disaster and the increase in gender inequity that you found?

Kimbro: I think it’s almost a multiplying effect. The households had what I would call an interestingly traditional division of labor before the storm. Both sides of the couple would espouse egalitarian gender ideas, but in how those relationships actually functioned, they were a bit more traditional.

After the storm, two-thirds of the women were working outside the home full time, but they were also managing all of the recovery process for the home. In many cases, it was just assumed that they would take on that role.

Henson: Houston seems to be a poster child for how a rapidly growing city can butt up against inherent geographic and climate risk, even before you take human-caused climate change into account. One of your subjects elevated their home and then told you, “We will have this home forever, and ever, and ever, and ever,” and another said, “That’s going to be our house for the rest of our life.” What is it that keeps so many of these families in the neighborhood, given such an obvious flood risk?

Kimbro: We do find that after disasters, communities sometimes feel closer to one another, that they have come through something together and helped each other survive. Those kinds of social bonds can be powerful to a community.

In this particular case, the neighborhood school was really prized for its academic standards. It was also racially and socioeconomically diverse, something the mothers valued as an experience for their children to have. So they were very tied to the school, which of course was also destroyed during Harvey. They really wanted to keep their kids as a part of that community. So that was another piece that was really holding them to the neighborhood.

Something that I don’t talk a lot about in the book is that this neighborhood is very close to the major Jewish institutions in the city. About one-third of my mothers were Jewish, so that too was an important factor tying them to the neighborhood.

Henson: What do your findings tell us about how climate change could intensify the work that all mothers face, especially those who practice “intensive mothering”?

Kimbro: Hopefully the book will help policy makers and other experts understand why people make the decisions they do. But in addition, I wanted to illuminate the role women are playing in these decisions, as well as the labor that they’re having to do just to keep their family in the spot that they want to be in.

I think a lot of people will read the book and think, These people are crazy. Why aren’t they getting out of here? I wanted to try and show the answer to that from their perspective.

Henson: How often in general did mothers use the flood as an opportunity to talk about climate change with their families? And how often do kids bring it up in their families?

Kimbro: It actually didn’t come up very much in the interviews until toward the end, when I would raise it. Virtually everyone agreed that what was happening to their neighborhood was a result of climate change. But I didn’t really get into what the kids thought about that as much.

Henson: What can we take away from the Bayou Oaks experience in other neighborhoods that might become increasingly at risk from repeated flood threats?

Kimbro: Managed retreat, or moving people out of flood-prone areas, is going to be more complicated than you would think by just looking at the economics of the situation. There’s the emotional hold to a neighborhood, a community sense of wanting to preserve the neighborhood, and these very important issues around schooling.

If we wanted to move people out of Bayou Oaks, the city or the county would have to figure out how to manage the school zone, so that the families could move out of the area, but still send their kids to this school that they valued so much. Right? That’s just one example.

Henson: What niche do you feel your study occupies in the broader field of disaster research?

Kimbro: I hope it joins this line of work like Lori Peek and Alice Fothergill that shows women’s role in disasters. And I hope it illuminates the strain and stress this experience puts on the family in all kinds of dimensions. Whether it’s financial or marital or parenting, it just compounds the difficulties in all those arenas. I think that’s a really important and under-told story of disaster.

Henson: How did this research affect you personally?

Kimbro: Especially at the beginning of the project, when I interviewed the women right after Harvey, I felt like I was carrying around 36 stories of trauma in my brain. I was teaching and doing research in my day job as well, and it was hard for me to focus on that. I started having to take a walk after I finished each interview to try to process. Once I started putting the stories down on paper, it also helped me process the stories and get through it. But it was a very heavy, emotional time for sure.

Henson: What do you hope non-specialist readers might take away from the book?

Kimbro: I hope it might help readers gain some insight into their own family dynamics and think a little bit about the gender division of labor in their own households. I also hope they’ll maybe think a little bit harder about how flood-prone the home where they are, or the one they might want to buy, actually is. Maybe bringing that more into the consciousness would be a good idea.