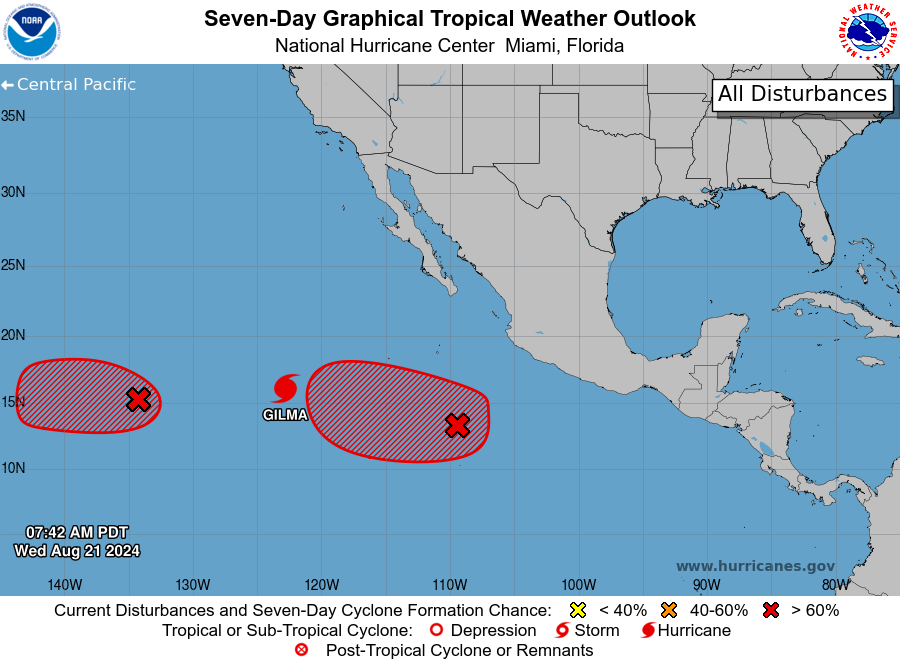

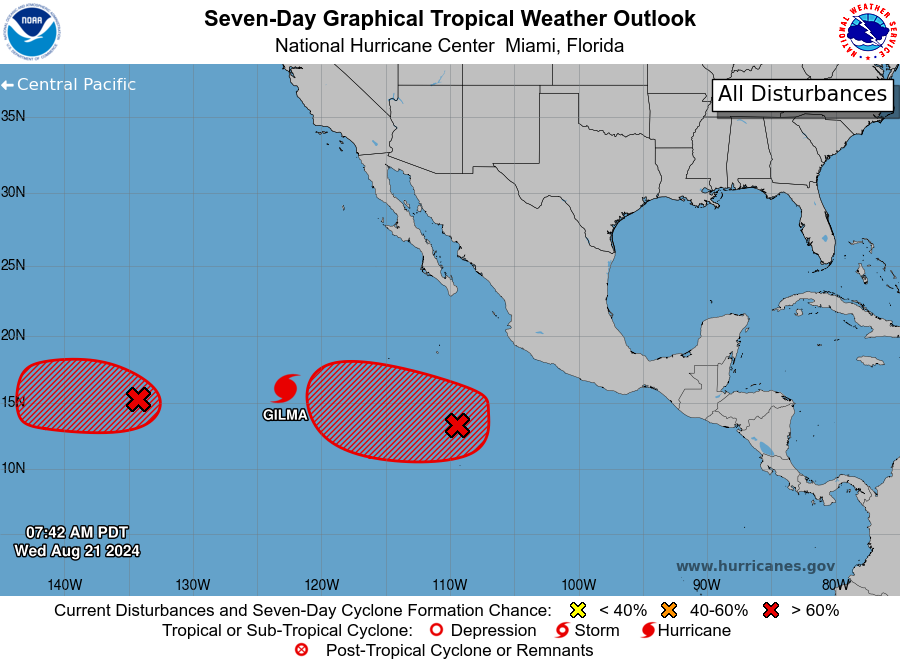

Coming into this hurricane season, there were breathless forecasts calling for anywhere from 20 to even 30 named storms from some folks. Government forecasts were more conservative but even they were the most active we’ve ever seen from NOAA. Colorado State, too. So, as we sit here on August 21st with next to nothing showing up in modeling for the next 7 to 10 days, it’s reasonable for the general public to ask questions about those forecasts.

Back on day one of hurricane season this year, we published a piece about ways this hurricane season could essentially fail, or at least turn out “less bad.” We advertise ourselves as no hype, which as comments occasionally show has good elements and bad elements (we seriously thank you all for your support and readership — and constructive feedback only helps us to do better!). But the question was basically “Are we overhyping this season?” And the answer was no: All the elements that you would want in place for a historically active season were in place. All those big time forecasts were justified.

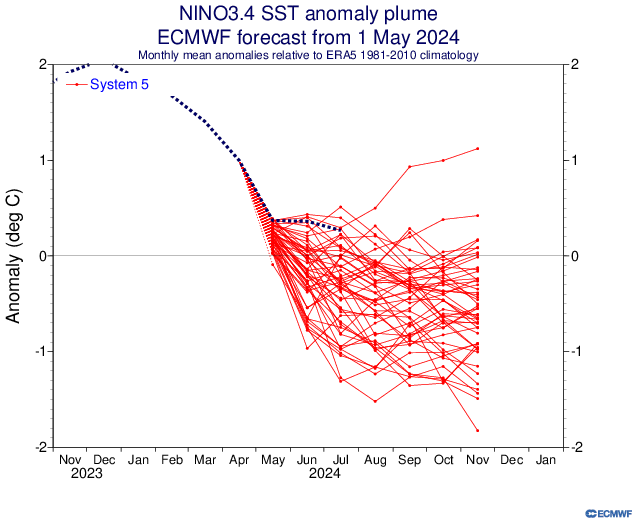

One of our potential fail modes was if La Niña developed too slowly. Indeed, the pace of the La Niña development this season, while uneven, has generally lagged the strongest projections. At least officially. Here’s a look at the May 1st European model ensemble outlook for the ENSO 3.4 region, the box of temperatures we look at to basically designate La Niña or El Niño.

We should begin closing in on an official La Niña designation in the next month or two, but we aren’t quite there yet. Keep in mind, this is by no means a perfect representation of things, and sometimes the atmosphere can behave more Niña-like even if we aren’t officially there yet. But this has not developed as aggressively as some modeling showed in developing in spring.

So, at a very, very distant level, perhaps that has something to do with it. Michael Lowry, in his excellent daily newsletter pointed out yesterday that wind shear has become almost too extremely reversed this month. Typically, during a La Niña, there is more of an easterly component from the wind that counteracts or reduces the usual west to east winds that can cause shear in the Atlantic, detrimental to hurricane development. In a twist of fate, there’s so much of an easterly component to the upper level winds this year that it’s actually causing easterly shear. Otherwise, we might be a good bit busier at the moment. If you look at the basin as a whole since June 1st, winds have been generally lighter than usual in the Caribbean and much of the Atlantic and a bit stronger than usual in the southwest Atlantic and in the Gulf.

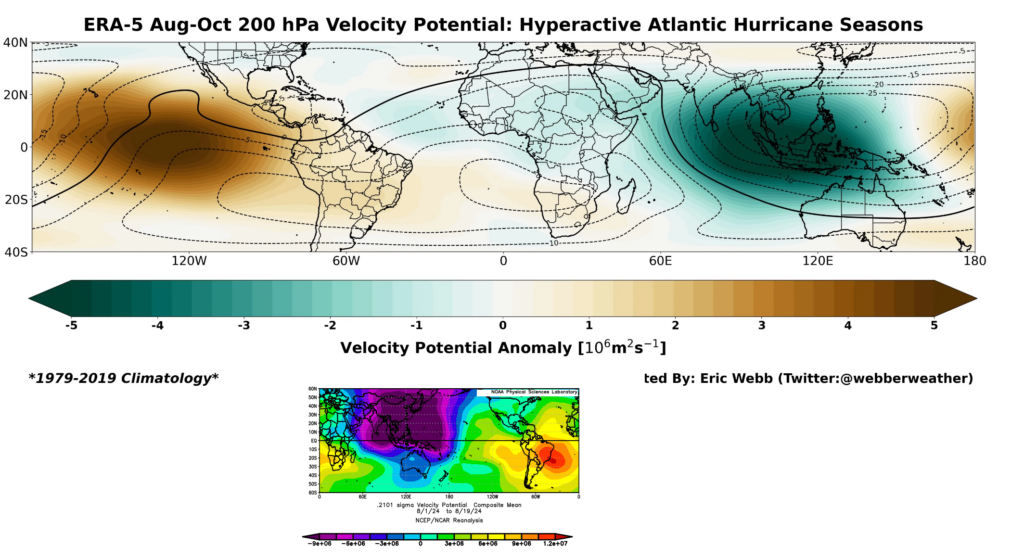

Let’s dig a little deeper. One thing that’s legitimately fascinating to me right now is what’s happening in terms of upper level background support in the atmosphere. Using a variable known as velocity potential, we can see that in historically active hurricane seasons, you would expect to see a significant area of rising air in the Indian Ocean, bleeding a bit into Africa (green on the top map below). Opposite to that, there would be a significant area of sinking air in the Eastern Pacific Ocean (brown colors below). Why is this important? In order to generate an active outbreak of storms in the Atlantic, you need disturbances tracking across Africa, which tend to get supported by rising air over and just east of there. You also prefer to see the Pacific undergoing sinking air, as a way to keep it from ‘robbing’ the favorable conditions for storminess. Sinking air suppresses thunderstorm development and tends to dry out the air a bit.

So what’s going on right now? So far this August, we’ve actually *had* what we would expect from a hyperactive season in the Indian Ocean. Click to enlarge the image below.

We have a ton of rising air in the Indian Ocean this month (purple & blue on the bottom map above). We have that extending into Africa. This is what you’d expect for a busy season. Where it differs, however is exactly where the sinking air (red/orange in the bottom panel above) is located. In a typical hyperactive season, this is focused over the Eastern Pacific. This year, it’s focused on the eastern side of South America. This is Matt speculating wildly here, but: I suspect that we’re seeing the right ingredients in place, but I think we are seeing them out of phase. The rising air in the Indian Ocean extends deeper into the Pacific, and there is more of a neutral Eastern Pacific signal right now. This is helping boost activity in the Pacific.

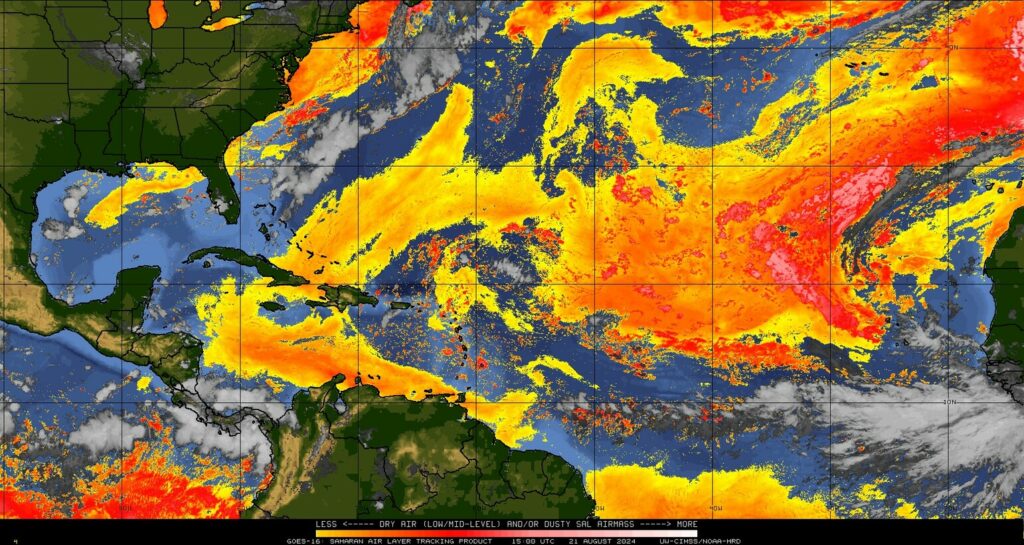

The problem with the tropics is that support like this generally moves from west to east, and eventually this will change. So the quiet now may change in a very, very quick way come September when this (presumably) shifts. For now, the Atlantic is still seeing rampant dust and a slightly displaced intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) which is sending disturbances off Africa too far north and into dust. So they die off earlier. This too will change.

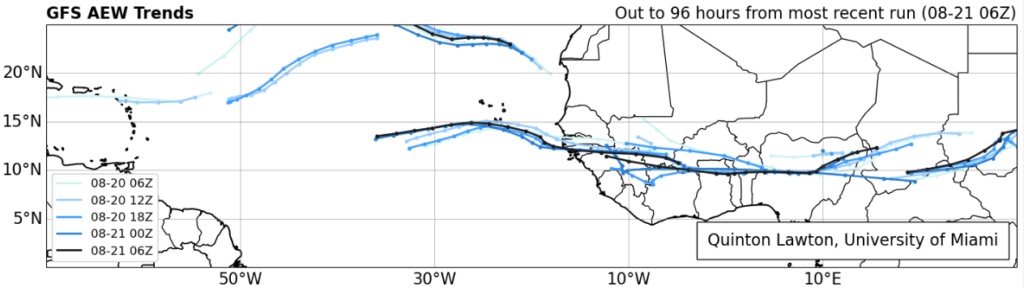

In fact, if you look at the forecast of African Easterly Waves (AEWs) from the latest GFS model, you can see this southward shift approaching heading into the next week or two. The waves lined up over Africa are about 5 to 10 degrees farther south in latitude about 4 days from now, which means they will emerge farther south and in more of a traditional area less exposed to Saharan dust in late August and September.

So, yes, things are almost certainly going to pick up soon.

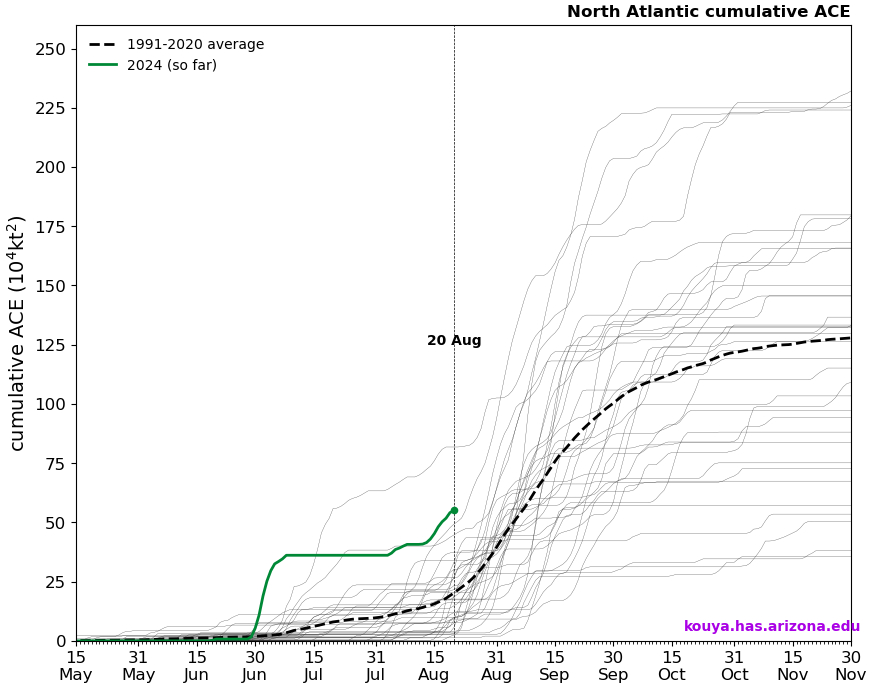

Despite perception, this season’s current accumulated cyclone energy is running nearly 3 times higher than usual! We’ve amassed as much ACE so far this season as we’d typically see by the peak day of hurricane season (September 10th). We’ve done this on the backs of only five storms so far, three of which have been hurricanes, and one of which (Beryl) smashed early season records in the Caribbean and Atlantic.

So despite the perception that this season has been slow to start, it actually has not been. In fact, 2024 is in rarefied air in terms of ACE to date. This perception might have to do with storm inflation, or the idea that we are naming more storms today than we did, say, 20 or 30 years ago. In 2020, basically the benchmark for recent historically active seasons, today marked the formation date for Hurricane Laura, the 12th named storm of the season. Here we are in 2024 sitting at five, and it’s no wonder the perception is skewed. Despite having more than twice as many storms to this point in 2020, we only had half the ACE (26 vs. 55 this year). 2020 kept churning out mostly sloppy storms until Laura, and then things got nasty. We’ve had three legitimate hurricanes this year and only about one “throwaway” storm (Chris). The takeaway message here is that: We can make up ground in September very, very fast. Very fast.

So, no, this season’s extremely active hurricane seasons have not been a bust so far, and they probably won’t end up being a bust overall. We’ve had a “bang for our buck” season so far with quality storms over quantity as, say, in 2020. And while we are in a lull now, the setup is probably going to change in 7 to 10 days to allow things to crank up in September. Never call it a bust. If it is one, we can discuss why in November. For now, use this quiet time to review your hurricane preparedness plans and supply kits. And stay tuned here for the latest through September.

Source link