Rapidly strengthening on Monday, Hurricane Ian is on track to slam into western Cuba early Tuesday morning, most likely as a major hurricane, before taking a complex and potentially devastating course along the Florida Gulf Coast. Whether or not Ian comes ashore on Florida’s west coast, the Tampa Bay area – which has not seen a major hurricane in more than a century – is facing one of its most dangerous hurricane threats in decades. People along Florida’s west coast need to take Ian with the utmost seriousness and consult local authorities for evacuation orders that could be extended quickly based on Ian’s progress.

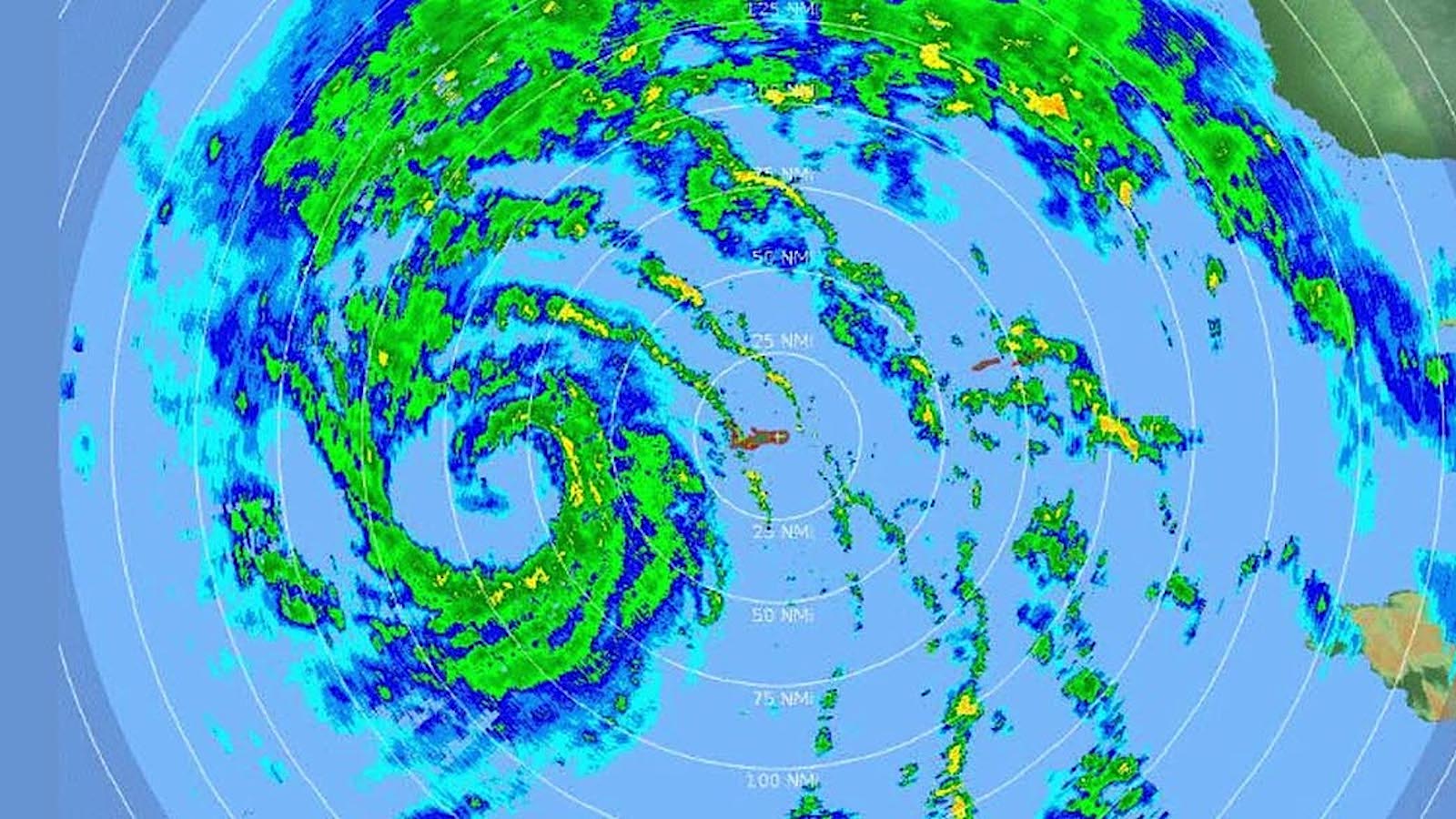

At 11 a.m. EDT Monday, category 1 Ian was 100 miles west of Grand Cayman, with top winds of 80 mph, headed northwest at 13 mph. Ian was bringing heavy rain showers to Jamaica, the Cayman Islands, and much of Cuba, as seen on Cayman Islands radar. The eyewall of Ian missed the Cayman Islands, and the peak winds observed at Grand Cayman on Monday morning were sustained at 28 mph, gusting to 44 mph.

Satellite imagery early Monday afternoon showed the symmetry, organization, and intensity of the storm’s heavy thunderstorms steadily increasing, and Ian had the look of a storm well on its way to becoming a major hurricane. Rainbands were already moving into South Florida on Monday afternoon.

Track forecast for Ian

Ian’s track will be fairly straightforward through Tuesday. The storm will move over or near the western end of Cuba early Tuesday, predicted by NHC to be a major hurricane at that point (see below). Havana will be on the stronger right-hand side of Ian: the city is very likely to experience tropical-storm-force sustained winds of 40 to 60 mph, and hurricane-strength winds are possible if Ian shifts just to the right or is larger than expected by Tuesday. Major impacts can be expected across far western Cuba, including 6 to 10 inches of rain along Ian’s path and storm-surge inundation of 9 to 14 feet on Cuba’s southwest coast near and just east of Ian’s track.

Forecast models have come into broad agreement on a general northward track for Ian from Tuesday through Thursday as it enters the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Ian will track toward a strong upper-level trough (a dip in the jet stream) projected to move from the eastern U.S. on Monday off the East Coast by Thursday. This steering pattern is expected to keep the principal threat of an Ian landfall from the Florida Panhandle to west-central Florida.

Despite this general model agreement, small differences in Ian’s track angle could have major implications for impacts in Florida.

West versus east: Through Sunday night, the GFS model continued to track Ian on the western side of guidance, taking Ian toward the Florida Panhandle, whereas the European and UKMET (British) models have been consistently further east, bringing Ian across or very near the Tampa Bay area (see Figure 1 above). Importantly, the 12Z Monday run of the GFS model shifted sharply eastward, much more in line with the ECMWF and UKMET forecasts, which both bring Ian into the Tampa Bay region.

Timing: The geography of Florida’s Gulf coastline means that a more westward track would keep Ian over the Gulf longer, thus increasing the amount of time Ian might be affected by the high wind shear and dry air expected to arrive around midweek (see below). In this case, a more northerly landfall could be much weaker in terms of peak winds, and it would occur later – perhaps as late as Friday on the Panhandle coast, versus a potential landfall in Tampa as soon as Wednesday if the eastern track proves more accurate.

A pause near Tampa? The trough across the eastern U.S. will have moved far enough east by Wednesday that it will exert less of a tug on Ian’s motion. The major models agree on a potentially crucial slowdown in Ian’s movement for about 24 hours, mainly from Wednesday into Thursday. Around Thursday, Ian should resume a somewhat faster northward motion.

Intensity forecast for Ian

Ian has nearly ideal conditions for intensification through Tuesday morning: very warm water of 30-30.5 degrees Celsius (86-87°F) with a high heat content, light wind shear, excellent outflow channels aloft, and a moist atmosphere (a mid-level relative humidity of 70%). Ian’s crossing over the western tip of Cuba early Tuesday morning is likely to interrupt the intensification process only briefly, as the few hours Ian spends over land should not significantly disrupt its core. Ian is likely to resume intensification over the warm waters of the southeastern Gulf of Mexico on Tuesday.

The 11 a.m. EDT Monday National Hurricane Center forecast for Ian was aggressive, explicitly predicting rapid intensification. NHC predicts Ian will go from a Cat 1 hurricane with 80 mph winds at 11 a.m. EDT Monday to a Cat 3 hurricane with 120 mph winds by 8 a.m. Tuesday, easily exceeding the minimum definition of rapid intensification (a 35-mph increase in winds in 24 hours). Further strengthening on Tuesday over the southeast Gulf of Mexico is predicted to make Ian a category 4 storm, with top sustained winds of 140 mph by Tuesday evening.

But by Wednesday morning, conditions for further intensification will become marginal, as a southwesterly flow of upper-level winds to the west of Ian brings an increase in wind shear; the 12Z Monday run of the SHIPS model predicted high wind shear of 20-35 knots would affect Ian on Wednesday, when the storm is expected to make its closest approach to Tampa. With dry air to the west of Ian at that time, the higher wind shear and drier air should cause weakening – and potentially rapid weakening – of the storm. Wind shear will continue to increase as Ian heads farther north on Thursday. Thus, for an earlier landfall to the south, Ian would be stronger; a more westerly track, resulting in a delayed landfall farther north, Ian would be weaker. Many of the models predict rapid weakening just before landfall on Thursday or Friday, and Ian could be reduced to a tropical storm if landfall occurs in the Florida Panhandle.

However, even for a delayed landfall as a tropical storm in the Florida Panhandle, Ian would be capable of major destruction. Steering currents weaken beginning on Tuesday morning, when Ian is expected to be moving northward at about 10 mph. By Wednesday, Ian’s forward speed will likely be about 7 mph, slowing to about 5 mph by Thursday. This very slow motion will allow Ian to pile up a large and damaging storm surge along the west coast of Florida. This surge will last through multiple high tide cycles, allowing it to penetrate far inland up narrow creeks and estuaries. Moreover, the slow motion of Ian near the coast will allow the storm to dump prodigious amounts of landfall, and subject the coast to extended battering winds, increasing the wind damage.

NHC currently has Ian topping out as a category 4 hurricane with 140 mph winds Tuesday night through Wednesday morning, when it will be to the west of Key West, Florida. The 12Z Monday run of the DTOPS model gave a 91% chance that Ian would intensify by 65 mph in 48 hours, becoming a Cat 4 with 145 mph wind by 12Z Wednesday. The top two intensity models for making 4- and 5-day forecasts in 2021, the HMON and the HWRF, predicted with their 12Z Monday runs that Ian would reach category 4 strength with 140-150 mph winds on Wednesday.

A dangerous and damaging storm surge expected in Tampa Bay

The 11 a.m. EDT storm surge forecast for Tampa Bay is for 5-10 feet of surge. This surge, characteristic of a category 1 or 2 hurricane, would be very dangerous and damaging for the region. The National Hurricane Center Storm Surge Risk Maps are helpful in showing the levels of inundation one might expect for various Saffir-Simpson category hurricanes, and they paint an alarming picture of how vulnerable the Tampa Bay region is (Figure 2). For a category 1 hurricane, the map shows that Pinellas County – home to St. Petersburg, and nearly one million people – may become completely cut off from the mainland. Portions of all four connecting bridges, as well as the main highway leading north – U.S. Highway 19 – will potentially be under as much as six feet of water. These evacuation routes would likely be cut off well before a hurricane arrives.

For those living in Hurricane Alley at low elevation, it’s important to know your evacuation zone (see Tweet below) and your storm surge risk using the NHC storm surge maps and floodfactor.com, a tool first made available by the First Street Foundation in 2020. This tool allows one to type in an address and see the specific flood risk for that property, a valuable new resource of a kind not previously publicly available. It’s free for non-commercial purposes.

Tampa Bay is highly storm-surge prone

Tampa Bay doesn’t get hit very often by hurricanes, because the city faces the ocean to the west, and the prevailing east-to-west trade winds at that latitude make it uncommon for a storm to make a direct hit on the west coast of Florida from the ocean. This is fortunate, since the large expanse of shallow continental shelf waters offshore from Tampa Bay (less than 300 feet deep out to 90 miles offshore) is conducive for allowing large storm surges to build. In a worst-case, with a powerful hurricane traveling north-northwestward at just the right speed parallel to the coast, the geometry of the coast creates a unique additional rise in the water level because of a phenomenon known as a coastal-ly trapped Kelvin Wave.

The last time Tampa suffered a direct hit by any hurricane was 1946, when a Category 1 storm came up through the bay. The Tampa Bay Hurricane of October 25, 1921 was the last major hurricane to make landfall in the Tampa Bay Region. This low-end Category 3 storm with 115 mph winds at landfall brought a storm tide of 10 – 11.5 feet (3 – 3.5 meters), causing severe damage ($10 million 1921 dollars.) The only other major hurricane to hit the city occurred on September 25, 1848, when the Great Gale of 1848, the most violent hurricane in Tampa’s history, roared ashore as a Category 3 or 4 hurricane with 115 – 135 mph winds. A 15-foot storm surge (4.6 meters) was observed in what is now downtown Tampa, and the peninsula where St. Petersburg lies, in Pinellas County, was inundated, making St. Petersburg an island. A large portion of the few human structures then in the area were destroyed.

When the 1921 hurricane hit Tampa Bay, about 160,000 residents lived in the four-county region, mostly in communities on high ground. Today there are 3.5 million residents in the region, and that number is growing by about 50,000 people per year. Sea level is now about a foot higher than in 1921, so a storm surge from the same storm would do much more damage.

Most of the population in the four-county Tampa Bay region lives along the coast in low-lying areas, about 50 percent of it at an elevation of less than 10 feet. More than 800,000 people live in evacuation zones for a Category 1 hurricane, and 2 million people live in evacuation zones for a Category 5 hurricane, according to the 2010 Statewide Regional Evacuation Study for the Tampa Bay Region. Given that only 46% of the people in the evacuation zones for a Category 1 hurricane evacuated when an evacuation order was given as 2004’s Category 4 Hurricane Charley threatened the region, the potential exists for high loss of life when the next major hurricane hits.

According to the second part of an excellent two-part series published earlier this year in the Tampa Bay Times, 11% of the properties in Tampa are at risk of flooding in a Cat 1 hurricane. In Pinellas County (where St. Petersburg is situated, and home to nearly one- million people), this number is 20% – with nearly $30 billion in property. No Florida county has both more buildings and more value at risk, the article reported: “More than 700 essential properties like places of worship, gas stations, schools, government buildings and public utilities are at risk of Category 1 flooding. Category 2 storms expose 500 more. Almost 400 hotel properties, most along Pinellas’ famed beaches, are similarly vulnerable.”

Tropical Storm Eta of 2020 in Tampa: a sobering experience

Even a strong tropical storm passing 70 miles west of Tampa Bay can generate a damaging storm surge, as discovered on November 11-12, 2020, when Tropical Storm Eta’s center passed about 70 miles to the west of Tampa. At the time, Eta’s sustained winds were 65 – 70 mph, and these were high enough to bring a storm surge of 3-4 feet above ground level to portions of Tampa Bay, said NHC. According to that 2022 Tampa Bay Time feature, in Pinellas County alone, more than 1,400 homes valued at $176 million flooded, one person was killed (a man walking through floodwaters was electrocuted), and 33 water rescues were performed.

In the entire Tampa Bay region, approximately 9,000 properties were inundated during Eta. Using storm surge modeling results from NHC, the Tampa Bay Times article explained that if Eta had hit with a water level just seven inches higher, 17,000 properties would have been inundated; a 22-inch rise in water level would have inundated 43,500 properties. Those numbers do not bode well for the future habitability of the Tampa Bay region with the current forecasts of sea-level rise fueled by global warming – and they raise serious concerns over potential impacts a Hurricane Ian could cause this week.

A worst-case scenario

A truly catastrophic worst-case scenario was portrayed by this morning’s 6Z (2 a.m. EDT) September 26 run of the HMON model, the top intensity model of 2021. In this model, which also did well for Fiona, the 66-hour forecast depicted a slow-moving category 4 Ian making landfall slightly north of Tampa Bay. This location, intensity, and forward speed would be capable of driving a 15-20-foot storm surge into Tampa Bay, making St. Petersburg an island. Catastrophic damages totaling more than $100 billion likely would result, and also possibly a high loss of life. Power, water, sewer, medical, and law enforcement services could be lost or severely curtailed for weeks. (The 12Z Monday run of the HMON model is almost identical to the 6Z Monday run discussed here.)

Given that this is only a 66-hour forecast from the top intensity model, residents of Tampa should be asking themselves today if they really want to stay in town with this scenario as a plausible outcome for Ian.

A best-case scenario

A best-case scenario was portrayed by this morning’s 6Z (2 a.m. EDT) September 26 run of the HWRF model. The 66-hour forecast from the model depicted Ian moving northwards about 200 miles to the west of the coast of Florida on Wednesday, bringing winds below tropical storm-force to Tampa Bay. The model depicted Ian rapidly weakening on Thursday and making landfall in the Florida Panhandle on Friday morning as a tropical storm with 45 mph winds. Such a track and intensity would still bring a damaging storm surge to the west coast of Florida and the Big Bend region, but total damage might well stay below $5 billion, and Ian might not end up getting its name retired. (The 12Z Monday run of the HWRF is less of a best-case scenario, as it brings Ian closer to Tampa Bay and now includes the distinct slowdown portrayed by other models.)

Bottom line: hope for the best; prepare for the worst.

Website visitors can comment on “Eye on the Storm” posts (see comments policy below). Sign up to receive notices of new postings here.

Source link