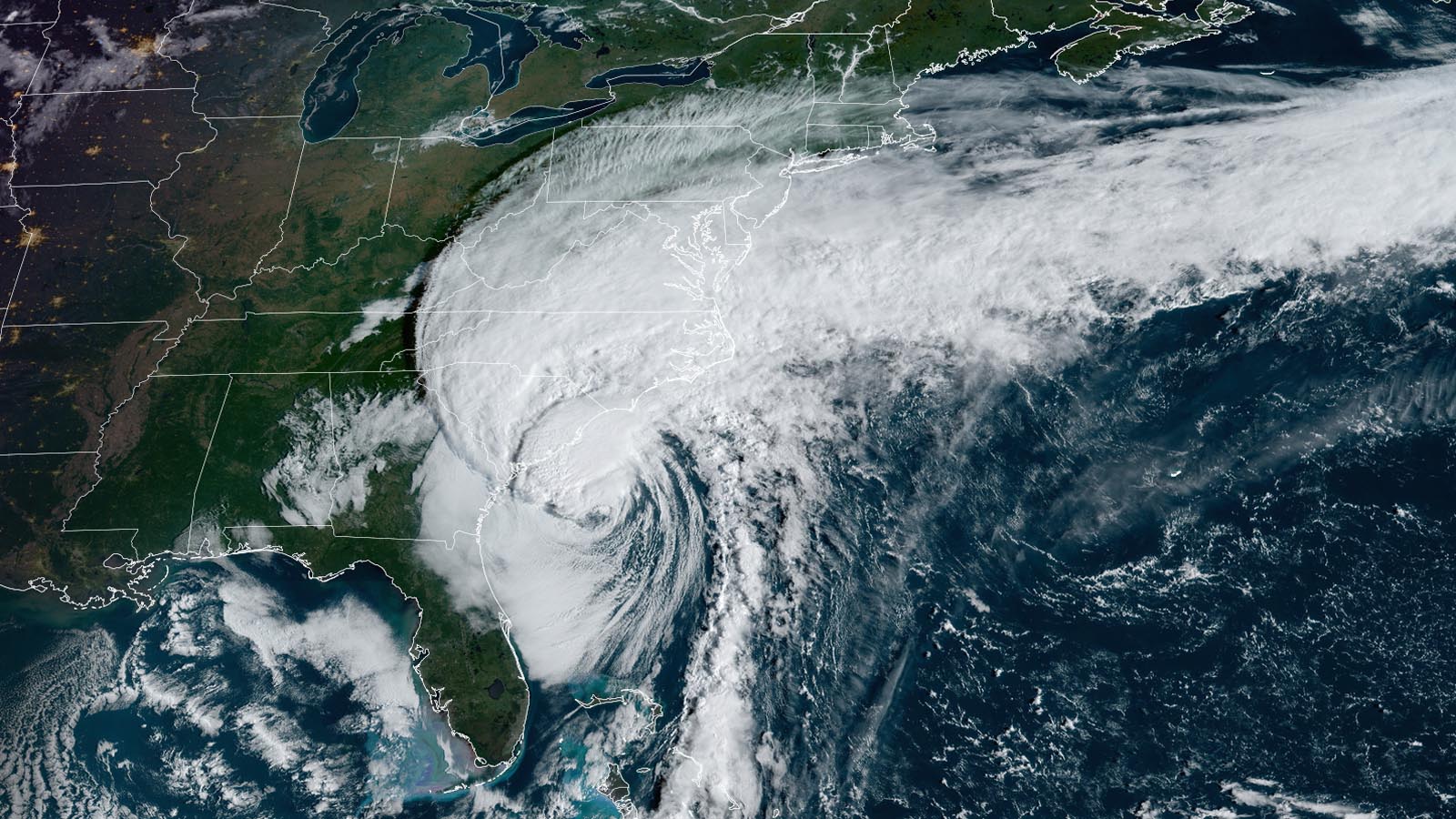

Hurricane Ian made landfall near Georgetown, South Carolina, about 55 miles northeast of Charleston, at 2:05 p.m. EDT Friday, September 30. At landfall, Ian was a category 1 storm with 85 mph winds and a central pressure of 977 mb. Ian’s largest impacts from this second U.S. landfall will likely be from storm surge flooding of up to 5 – 7 feet, and inland flooding from rains of 4 – 8 inches. However, the damage from this second U.S. landfall will very likely be more than a factor of 20 less than what occurred from its landfall in southwestern Florida. Hundreds of people were rescued on Thursday from the hardest-hit areas in southwestern Florida, and severe flooding from record-setting rains affected parts of central and northeast Florida.

Staggering insured damages

Even with Ian’s course of destruction still incomplete, it is virtually certain that the storm will rank as one of the most damaging in U.S. history. CoreLogic estimated that insured damage from Ian in Florida alone would range between $28 to $47 billion; Fitch Ratings estimated insured losses of $25 to $40 billion. Many billions more will be incurred by residents who lack adequate insurance. Florida has a strong building code for hurricane wind damage, but much of the damage from Ian came from storm surge and inland flooding, and home insurance does not typically cover these water-related threats. Only a small fraction of residents in southwest Florida outside the 100-year flood plain have federal flood insurance. Total damage typically ends up a factor of two higher than insured damage, so the total price tag for Ian’s rampage might be in the $50 – 100 billion range, which would make it one of the top-ten most expensive weather disasters in U.S. history (Figure 1).

Early Friday afternoon, torrential rains in excess of an inch per hour were falling along the coast of South Carolina, which was receiving the brunt of a primitive eyewall that Ian had built just before landfall. No rivers in South Carolina or North Carolina were at flood stage on Friday afternoon, but five rivers in those two states are predicted to reach at least minor flood stage this weekend. In Florida, however, 14 river gauges were at major flood stage on Friday afternoon from Ian’s rains, including a number at their highest levels on record.

Wind gusts of 40 to 70 mph were common along the coast of South Carolina late Friday morning into early Friday afternoon. A WeatherFlow station in Charleston Harbor recorded a wind gust of 92 mph at 12:44 p.m. EDT Friday, and a WeatherFlow station at Morris Island Lighthouse reported sustained winds of 75 mph with a gust to 82 mph shortly before 2 p.m. EDT.

Damaging storm surge predicted in parts of South Carolina and North Carolina

The portions of the Carolina coast to the right of where Ian’s center makes landfall are predicted to receive a damaging storm surge, with up to 5 to 7 feet of surge predicted along the northeastern coast of South Carolina. The timing of the surge with respect to the tide will be important: The tidal range is more than five feet along much of the coast, and some of the highest tides of the month – the king tides – are occurring this week. High tide at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, was at 11:30 am EDT Friday, and the highest water levels (storm tide) associated with Ian’s landfall in South Carolina occurred about an hour and a half after that.

Major flooding occurred early Friday afternoon at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, where a storm surge of 6.2 feet and a storm tide of 5.17 feet above Mean Higher High Water (MHHW) was observed at 1:36 p.m. Friday, September 30. This was that location’s third highest water level on record – far below the 8.77 feet recorded during Hurricane Hugo in 1989, but still enough to produce significant flooding. (See Tweets below from Garden City and Lichfield Beach, both within 10 miles of Myrtle Beach). Second place at Myrtle Beach is held by Hurricane Matthew of 2016 (6.13 feet). Records extend back to 1957 at the site.

Mostly minor to moderate flooding from Ian’s storm surge in southeast U.S.

Along the Florida and Georgia coast, Ian’s second U.S landfall has caused mostly minor to moderate coastal flooding, with no areas of major flooding observed. In northeastern Florida near Jacksonville, the St. John’s River at Mayport reported a water level 2.48 feet above Mean Higher High Water (MHHW) on Thursday afternoon, causing moderate flooding. This was the third-highest water level on record there, with records back to 1897. Only Hurricane Matthew in 2016 (3.22 feet) and Irma in 2016 (2.80 feet) brought higher water levels.

Fernandina Beach, Florida, reported that a water level of 3.36 feet on Thursday afternoon also caused moderate flooding, the sixth-highest water level on record. Records extend back to 1897 at the site.

Fort Pulaski, Georgia’s minor storm surge flooding did not rank among the top-10 values on record.

In South Carolina, Charleston Harbor had a crest of 1.16 feet, below the threshold of minor flooding, with the midday Friday high tide. This is below the peak of 1.83 feet on Thursday morning, and not among the 10 highest crests on record there.

The crest of 3.54 feet at Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina, at 1 p.m. EDT Friday fell just below the threshold for moderate flooding, as the fourth-highest water level on record there, behind Hurricane Hazel (1954), Fran (1996), and Florence (2018). Records extend back to 1954 at that site.

Ian is predicted to transition to an extratropical storm Friday night, and dissipate by Saturday night.

Power out to 1.8 million in Florida, 270,000 in Carolinas, and much of western Cuba

As of 3 p.m. EDT on Friday, September 30, Ian had knocked out power to approximately 1.8 million customers in Florida (approximately 16% of the state’s customers), down from a peak of 2.7 million on Thursday, according to poweroutage.us. In South Carolina, Ian’s winds had knocked out power to 210,000 customers, and 60,000 were without power in North Carolina.

In Cuba, where Ian had caused an island-wide blackout on Tuesday, the power was still out Friday in much of the capital of Havana, as seen in nighttime visible satellite imagery (Figure 3). Reuters reported isolated street protests over the long power outage in Havana on Thursday night. Ian hit western Cuba on Tuesday as a category 3 hurricane with 125 mph winds, killing two people.

Meanwhile, in Puerto Rico, which had suffered an island-wide power outage on September 19 because of Hurricane Fiona, the power was still out to 230,000 customers on Friday, about 16% of the island’s customers.

New system likely to develop in eastern Atlantic

A disturbance that moved off the African coast on Thursday, not yet granted an “invest” number, could develop over the next few days as it drifts generally westward. The broad disturbance was at low latitudes in the eastern tropical Atlantic on Friday, around 200 miles west of the African coast. Convection (showers and thunderstorms) was on the weak and scattered side, and it will likely take several days for any development to occur.

In its Tropical Weather Outlook issued at 2 p.m. EDT Friday, the National Hurricane Center gave the system a 10 percent chance of development by Sunday and a 60 percent chance by Wednesday.

The new disturbance will be moving through a moist mid-level environment free of intense wind shear or a dry Saharan Air Layer and atop warm sea surface temperatures (SSTs) around 28 degrees Celsius (82 degrees Fahrenheit).

Many of Friday morning’s ensemble runs of the GFS and European models show a tropical depression forming early next week. A break in the subtropical ridge of high pressure should allow the incipient system to angle northward at first, toward the central North Atlantic. Whatever develops could end up being a long-lived pest, as longer-range models suggest the ridge could restrengthen and push the system toward the northwest Atlantic subtropics, where SSTs remain unusually warm. The next name on the Atlantic list is Julia.

Website visitors can comment on “Eye on the Storm” posts (see comments policy below). Sign up to receive notices of new postings here.

Source link