An above-average Atlantic hurricane season is once again likely in 2022, the Colorado State University (CSU) hurricane forecasting team says in its latest seasonal forecast, issued April 7. In fact, last year’s hyperactive 2021 season is one of the top analogues.

Led by Dr. Phil Klotzbach, with coauthor Dr. Michael Bell, the CSU team is calling for an active Atlantic hurricane season with 19 named storms, 9 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes, and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) of 160. In comparison, the long-term averages for the period 1991-2020 were 14.4 named storms, 7.2 hurricanes, 3.2 major hurricanes, and an ACE of 123.

The CSU outlook predicts the odds of a major hurricane hitting the U.S. to be 71% (long-term average: 52%). It gives a 47% chance for a major hurricane to hit the East Coast or Florida Peninsula (long-term average: 31%), and a 46% chance for the Gulf Coast (long-term average: 30%). The Caribbean is forecast to have a 60% chance of having at least one major hurricane pass through (long-term average: 42%).

The CSU forecast uses a statistical model honed from 40 years of past Atlantic hurricane statistics, plus output from the ECMWF (European) model, UKMET model, and Japan Meteorological Agency model to augment the statistical technique.

Analogue years

Six years with similar pre-season January, February, and March atmospheric and oceanic conditions were selected as “analogue” years that the 2022 hurricane season may resemble. These years had La Niña conditions the previous winter, and then neutral or weak La Niña conditions during the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season (August-October). The CSU team also selected years that had near- to above-average sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the tropical Atlantic. The analogue years were:

1996 (13 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 6 major hurricanes);

2000 (15 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes);

2001 (15 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes);

2008 (16 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes);

2012 (19 named storms, 10 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes); and

2021 (21 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes).

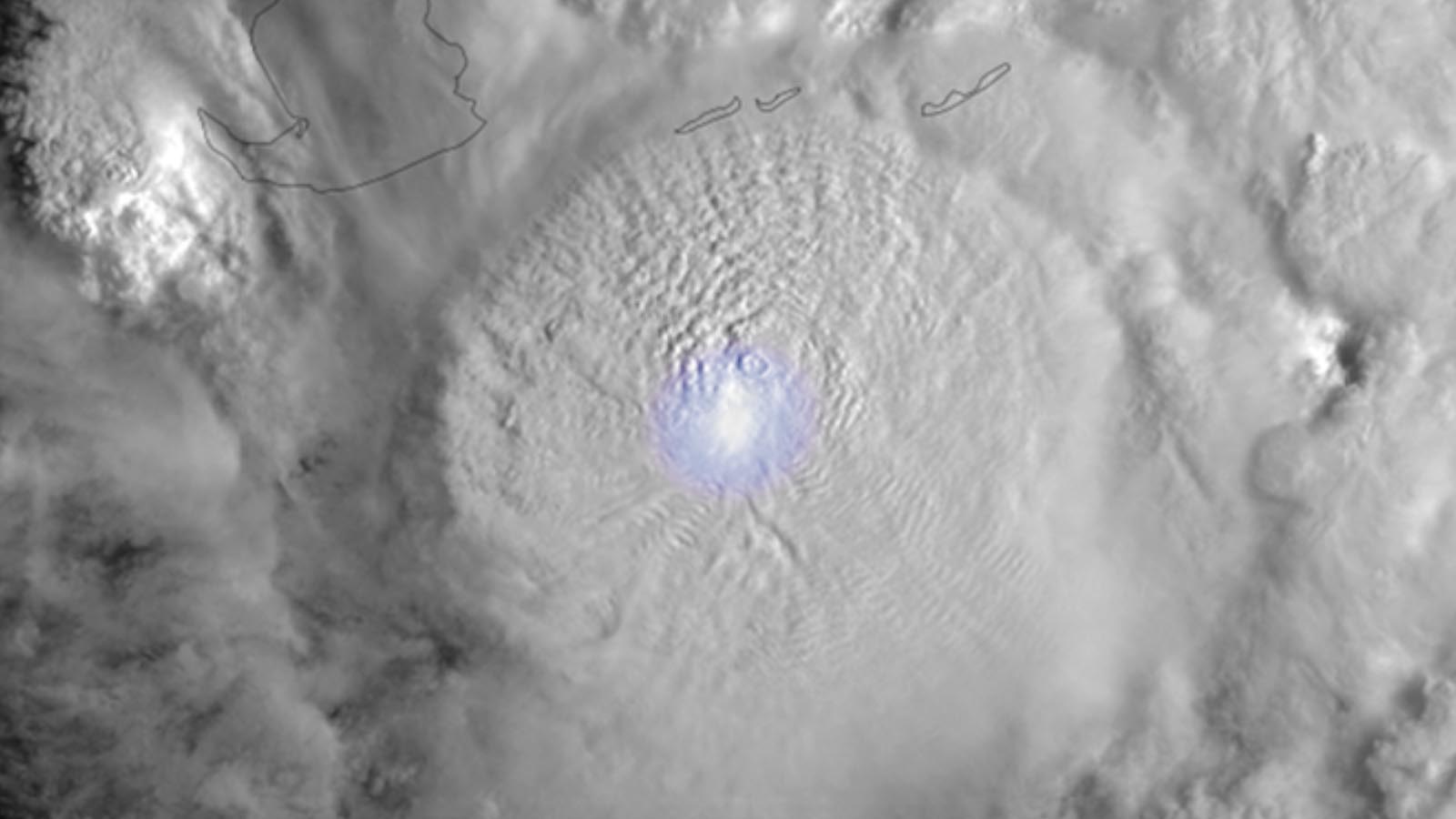

The average activity for these years was 16.5 named storms, 8.5 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes, and an ACE of 160 – well above the long-term average. Interestingly, last year was one of the analogue years, and the sea surface temperature pattern on April 7 both this year and last year looked remarkably similar (Figure 1).

The CSU team cited two main reasons, addressed below, that 2022 may be an above-average hurricane season:

1) A significant El Niño seems unlikely.

The current weak La Niña event in the Eastern Pacific appears likely to continue into the summer (53% chance), NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center (CPC) predicted in its latest March 10 monthly advisory. NOAA gave a 90% chance of La Niña or neutral conditions during the August-September-October peak portion of hurricane season, and only a 10% chance of El Niño. El Niño conditions favor a slower-than-usual Atlantic hurricane season as a result of an increase in the upper-level winds over the tropical Atlantic that can tear storms apart (higher vertical wind shear). If neutral or La Niña conditions are present, instead, an active hurricane season would be more likely. The CSU team favors neutral conditions during the peak portion of hurricane season.

Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) were about 0.7 degrees Celsius below average during the past month in the so-called Niño 3.4 region (5°S-5°N, 120°W-170°W), where SSTs must be at least 0.5 degrees Celsius below average for five consecutive months (each month using a three-month centered average for departure of temperature from average) to qualify as a weak La Niña event.

Reviewing the latest predictions from 20 statistical and dynamical El Niño models for the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season in August-October, 13 call for neutral conditions, one predicts El Niño conditions, and six predict La Niña conditions.

2) The current SST pattern correlates with active Atlantic hurricane seasons

The eastern and central tropical Atlantic currently have near-average sea surface temperatures (SSTs), while the Caribbean and most of the subtropical Atlantic are warmer than normal. “Overall, the current SST anomaly pattern correlates relatively well with what is typically seen in active Atlantic hurricane seasons,” the forecasters said. “Anomalous warmth in the subtropical eastern Atlantic and in the Caribbean in March correlate well with active Atlantic hurricane seasons.”

As is its practice, the CSU team included this standard disclaimer:

“Coastal residents are reminded that it only takes one hurricane making landfall to make it an active season for them, and they need to prepare the same for every season, regardless of how much activity is predicted.”

A caveat: April hurricane season forecasts have little or no ‘skill’

On average, April forecasts of hurricane season activity have had no “skill,” or even negative skill when computed using the Mean Square Skill Score (Figure 3). A negative skill means that a forecast simply using climatology would do better. April forecasts must deal with the so-called “spring predictability barrier.” In April, the El Niño/La Niña phenomenon commonly undergoes a rapid change from one state to another, making it difficult to predict whether El Niño, La Niña, or neutral conditions will be in place for the coming hurricane season.

CSU’s April 2021 forecast a year ago had predicted an above-average Atlantic hurricane season for the year, with 17 named storms, 8 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes, and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) of 150. That forecast was quite accurate, since the 2021 season ended up with 21 named storms, 7 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes, and an ACE of 176. The CSU forecast for the 2020 season also proved quite accurate.

The next CSU forecast, due June 2, is worth close attention, as late May/early June forecasts have shown considerable skill over the years. NOAA is to issue its first seasonal hurricane forecast for 2022 in late May. The British private forecasting firm Tropical Storm Risk, Inc. (TSR) on April 12 is to issue its first 2022 Atlantic hurricane season forecast. Its December 10, 2021 forecast for the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season called for an above-average season for number of named storms, with 18, but a near-average season for other metrics, with 8 hurricanes, 3 intense hurricanes, and an ACE index of 122.

Also see: How to make an evacuation plan

Bob Henson contributed to this post.

Website visitors can comment on “Eye on the Storm” posts (see below). Please read our Comments Policy prior to posting. (See all EOTS posts here. Sign up to receive notices of new postings here.)

Source link