“My home territory.”

That’s how fiction writer Alan Gratz describes his focus on those generally eight- to 14-year-olds and in the fifth-to-eighth middle grades, between their elementary and secondary school years.

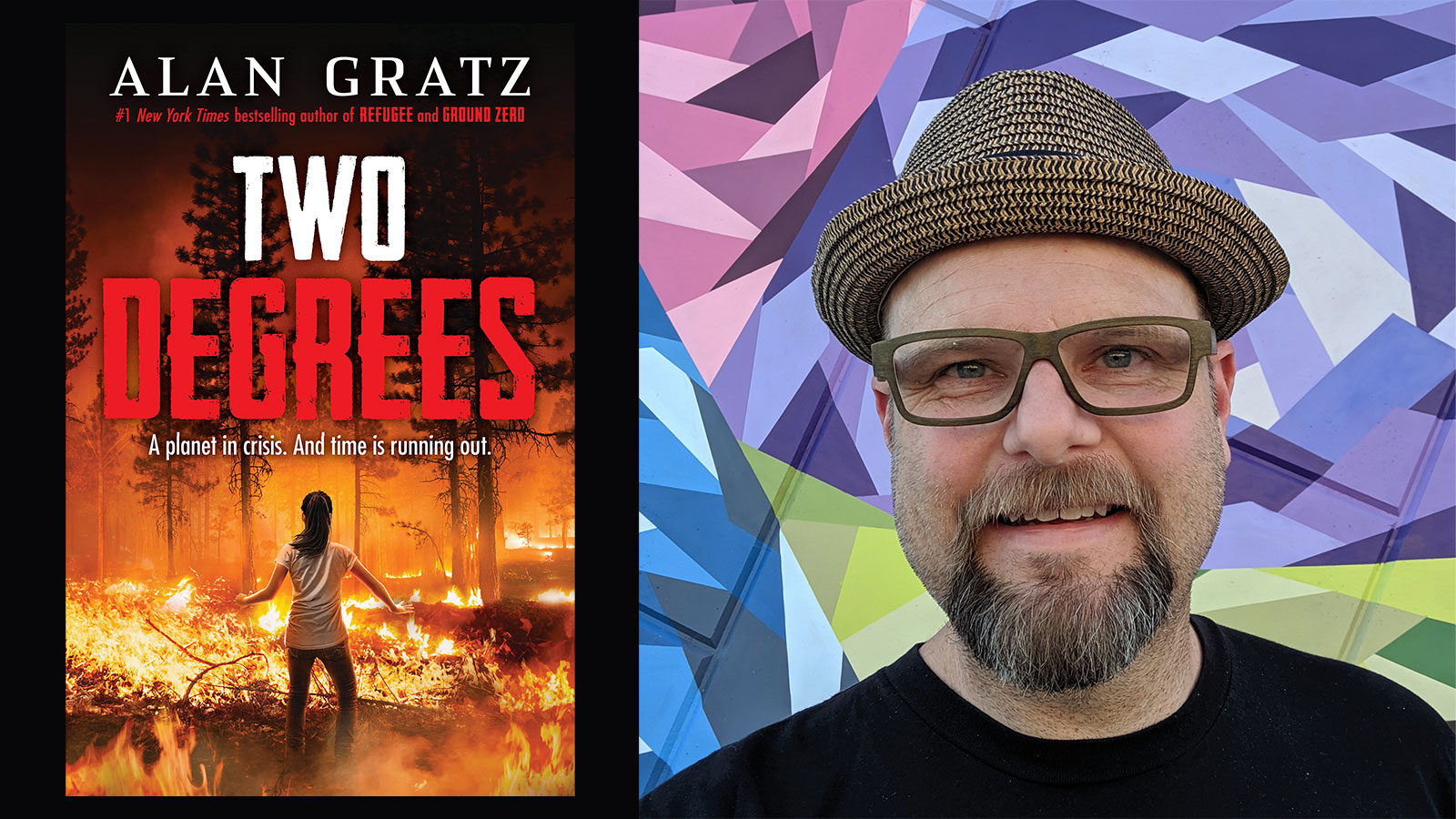

Gratz has written a number of books for what he prefers to call “young people” or “kids” – including, most recently, “Two Degrees” focusing on climate change. Gratz, a resident of Asheville, N.C., sat for a Zoom interview with Yale Climate Connections to discuss his latest book, published this past October.

Bud Ward: Is it accurate to describe “Two Degrees” as science fiction?

Alan Gratz: Great question. That term is often defined in the U.S. as fiction of the future, addressing things that can’t happen yet except through magical means. By that definition, no. I prefer to call it “fiction that is science-based.”

Ward: Can you estimate the proportion of the book’s content that you consider to be fiction versus the part you consider to be climate science?

Gratz: That’s a difficult question, but I assure you it’s a conversation my Scholastic Press editor and I were having constantly throughout the writing. In my first draft, I had chapters and chapters on the peer-reviewed science – too much science. My editor wanted it to be ‘subversively educational’ – but with a need to consider what science talk could be deleted that is killing the pace of the book for a youthful audience.

The number one thing I’m shooting for is to write an entertaining book. I want kids to keep turning the page. Because if they’re not interested in the story, if it’s not a page-turner, they’re not staying with me for the science. Every time I had a lot of science, the question had to be “Is there so much science that it’s slowing down the story, and I’m going to lose my readers?” And then it became a question of ways to work the science in to places that were already focused on action and adventure, identifying where the science could work its way in tangentially. I might say “Two Degrees” is 80% action and adventure, and 20 % science.

The tensions being scientifically ‘didactic’ while being a page-turner to 8 to 14 year olds.

There was a part of me that really wanted to be didactic, because climate change is a big problem, and unless we start talking about it honestly with kids, it’s not going to get fixed. I admit I have less and less patience now with stories that are just a metaphor for climate change. I don’t want to read a story that is metaphorical for climate change. I want to read a story that is literally about climate change. The time for just talking around climate change is gone, the need for talking directly about climate change has been with us for some time.

Ward: Given the understandable need to appeal to young readers with what you call a “page turner,” what steps did you take to ensure the accuracy of the scientific or evidence-based climate science as you address it in the book?

Gratz: Well, that’s part of the reason it took so long for me to write this book, about two full years. I did my homework beforehand, and actually I used a lot of the Yale resources for background, spoke with numerous climate scientists, attended regular Friday NOAA National Environmental Information Center weekly Zoom meetings with Asheville scientists, and listened to what they have to say, and I interviewed many of them. I of course did lots of readings.

But in the end, I know that I am not a climate scientist. I’m a fiction writer, but I only naturally write about a lot of things that I’m not an expert on. For instance, my “Allies” book on D-Day and my “Ground Zero” book on 9/11. I’m not an expert, but I find people who are smarter than me, who have spent their whole lives studying these things. And I talk with them, I do my homework.

Ward: Your “Two Degrees” book jacket says one of your goals is to inspire readers to “take action” on climate change. How specifically does it do that?

Gratz: I chose to set this book in the present, rather than to outline a seriously climate-changed future. I want the book to be a horror story, but it is supposed to also be a wake-up call for kids who live comfortably and don’t experience climate change as much as other kids in the world do. Even if they’re not feeling the impacts of climate change, even if they’re not feeling it as much … Even if they’re riding out the storm in a yacht, I want them to realize there are other people who are clinging to the wreckage in the storm and already having a much worse time of it.

That’s one of the beauties of addressing middle grade readers. At that age, they are really empathetic, and they care a lot about other people. They haven’t become so wrapped-up in just their own lives. It’s weird: kids go from being totally wrapped-up in their own lives at a younger age, to then getting to middle school and realizing that, “Oh my gosh. I’m a human being, and I live among other human beings.” They begin to realize that they are citizens of the world.

Also, middle graders love justice. I think it’s one of the reasons World War II books are so popular — people crave justice. And by the time they’re in those middle grades, kids have an innate sense of justice: “Oh my gosh, that person got something, and that person didn’t: That’s just not fair. Those people are suffering from climate change, but other people aren’t: That’s just not fair. What’s going on?”

I hope “Two Degrees” prods them on, just as has happened with Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg. And the same thing has happened and can happen with a lot of American youths.

I also wanted to make sure the book was broadly representative, with lots of geographic diversity and reflecting diverse climate change impacts, with kids affected all over the world and “quick hits.” So the book reflects diversity of place, of experience, of economic levels and races, and family structures. I was determined that the book cover as many bases as possible.

Ward: Your book was published just over a month ago, but is there any early indication that teachers are picking up your book as part of their curricula?

Gratz: It’s really still anecdotal at this point, but some teachers have indicated on social media that they’re making it their Friday reading book, reading it out-loud with their students. They have used my other books in that way, and I’m hoping the same will happen with “Two Degrees.”

Scholastic Press book fairs have been around in schools and in school libraries for about a hundred years, and they’ve given my earlier kids books immense amounts of exposure. So I’m hopeful. I say that I’m now in the business of helping teachers understand that there are some [climate denialism books] that they should ignore and make sure they’re using responsible science as a criterion in their classrooms.

Ward: So how do you get the message across to young readers about the need for them to engage in addressing the risks posed by climate change, without simply bumming them out about the very real prospects of a much different and more challenging future?

Gratz: One thing I keep in mind is that people in general do not respond well when you tell them that they’re bad people. When you scold them, when you call them out, their natural human response is to get defensive. And they push that criticism away. So it’s important not to be accusatory. Instead of saying “You’ve made some mistakes, you’re a bad person,” I say “look at this bad situation. What do you think a good person would do to fix this bad situation.” And then I invite the reader to be that good person.

I hope “Two Degrees” leaves kids with the message that human beings are amazing…. My message to the kids is that we can do this, we’ve done it before, and we’re incredible problem solvers. My message to the kids is that climate change is caused by humans and that we have the ability to change things.

That’s the good news, that if humans are causing climate change, which we are, that means it’s in our power to fix it. It’s not like it’s an asteroid that came down and is causing another ice age. That’s the good news, and it’s an important part of the message I hope to share with younger readers and, perhaps through them, also with others.

FICTION

“Two Degrees,” by Alan Gratz; New York: Scholastic Press, 384 pages (2022).

Source link