Just two days after Los Angeles experienced its strongest tornado since 1983, a volatile severe weather setup driven by the same upper-level storm was taking shape for Friday, March 24, from Louisiana and Arkansas into Mississippi.

The NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center placed the region under a moderate risk for severe weather—its second highest of five risk levels—and warned that an outbreak of strong tornadoes could emerge by Friday evening.

Both the L.A. tornado and the potential Mississippi Valley outbreak can be attributed in large part to a powerful upper-level low racing along the polar jet stream. On Friday, this low will be “lifting” northeast toward the Great Lakes. As it does so, a surface low will intensify and pull very moist, warm, unstable air from the Gulf of Mexico into the severe-weather risk area. This “just in time” arrival of rich moisture means that there may not be much preceding thunderstorm activity to neutralize the atmosphere, which in turn raises the odds for distinct, long-lived supercell thunderstorms that can produce the most dangerous type of tornado.

Southwest winds at the jet-stream level will be racing at more than 120 mph. The contrast between south-to-southeast winds near the surface and stronger south-westerlies just above the surface will lead to potent wind shear, another key ingredient in tornadic storms.

High-resolution models, including the HRRR, were the most bullish in depicting tornadic supercells forming by late afternoon in southern Arkansas and northern Louisiana, moving across much of Mississippi and western Tennessee in the early evening. The result could be one or more intense tornadoes racing through the area after dark—a dangerous combination of risk factors.

Tornadoes will also be possible within lines and clusters of storms expected to erupt as far north as western Kentucky; overall, these twisters would more likely be shorter-lived and less intense than those further south.

A rare Los Angeles tornado grips social media

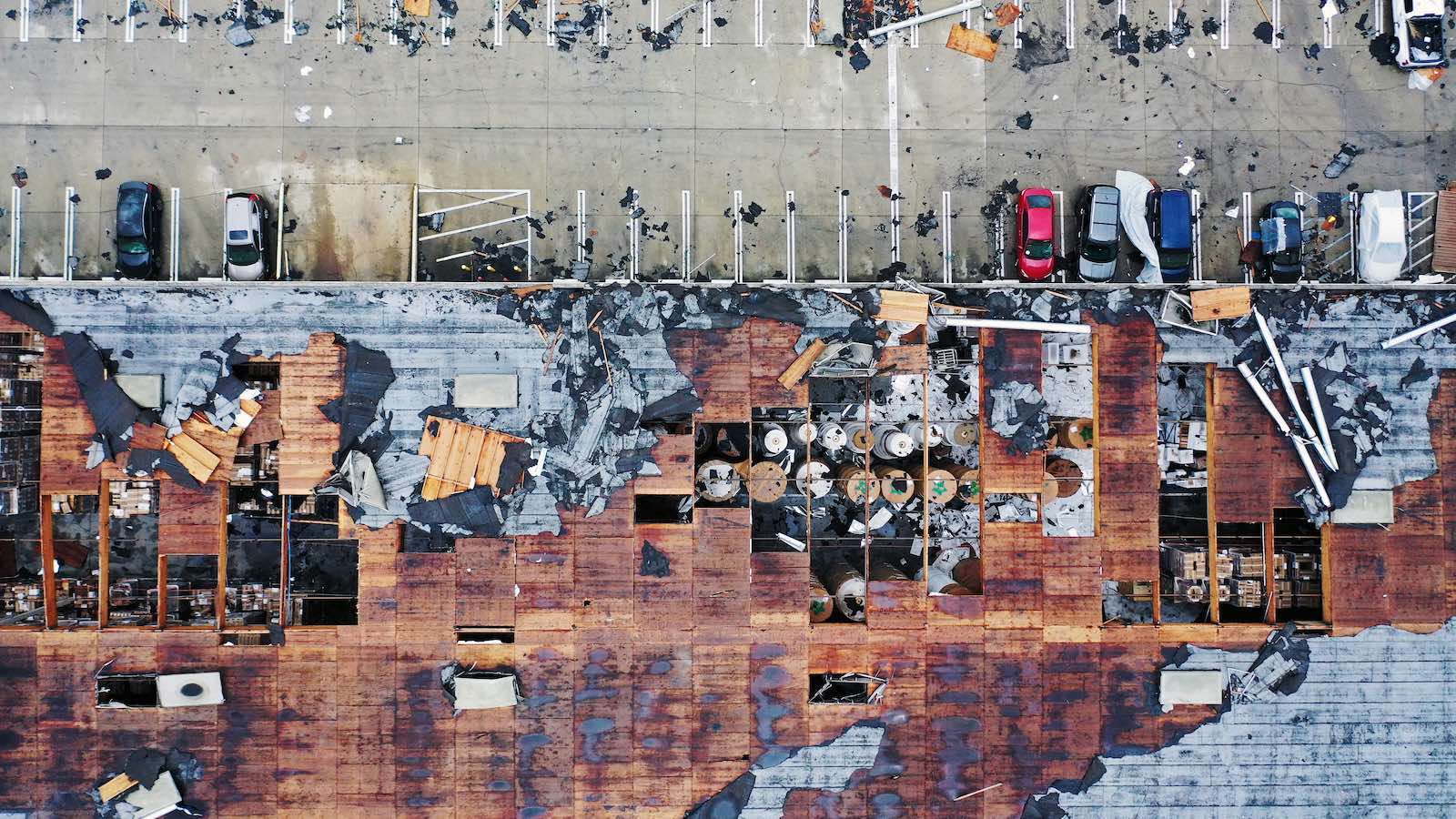

For a city built on the power of imagery, this was a show-stopper of a video. Above is footage of the brief but spectacular L.A. twister that tore on Wednesday, March 22, through an industrial area in the Montebello neighborhood, less than 10 miles east-southeast of downtown Los Angeles. The tornado injured one person and damaged 17 structures.

Meteorologists with the National Weather Service in Los Angeles reported on Thursday that the Montebello tornado had top winds of 110 mph, qualifying it as an EF1 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale. That made it the metro area’s first F1/EF1 tornado since the one that struck Long Beach on Jan. 9, 1998, and the strongest tornado in the city itself since an F2 struck on Mar. 1, 1983. (Although the original Fujita Damage Scale became the Enhanced Fujita Scale in 2007, the older F ratings correspond precisely in strength and damage to the later EF ratings. The only change was a decrease in the wind speeds at each level, as it was discovered that a given amount of damage could be produced by weaker winds than originally thought.)

If it hadn’t struck in the heart of the nation’s second-largest city, the Montebello tornado might have gained little notice on its own merits. The tornado lasted only about three minutes, covered a track just 0.42 miles long (just a few city blocks, or 0.67 km) and spanned about 50 yards (150 feet or 46 meters).

One day earlier, (on Tuesday, March 23) a weak tornado just 25 yards wide that originated as a waterspout struck Carpinteria on the Pacific Coast a few miles east of Santa Barbara. The NWS survey rated this twister as EF0, with top winds of 75 mph. One injury and some mostly-minor property damage were reported.

Further north on Tuesday, a complex and intense surface low associated with the upper-level storm moved inland across the Bay Area, bringing heavy rain and exceptionally strong winds that downed trees and power lines. Two smaller-scale lows, or “meso-lows”, rotated around each other in a miniature version of the Fujiwhara effect that occurs with some tropical cyclones.

A busy spring for severe weather may lie ahead, based on embryonic seasonal forecasts

Several scientists who’ve been experimenting with multi-week and seasonal forecasts of severe weather have predicted over the past several weeks that spring 2023 could be more active than usual. Their prognoses—including important caveats—can be found in our in-depth post from March 16.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.

Website visitors can comment on “Eye on the Storm” posts. Comments are generally open for 30 days from date posted. Sign up to receive email announcements of new postings here. Twitter: @DrJeffMasters and @bhensonweather

Source link