After bottoming out on Sunday morning as a category 2 storm with 105 mph winds, Hurricane Lee is intensifying once more. Lee is predicted to regain category 4 status by Monday evening, and make a sharp northward turn by the middle of the week, taking it on a path toward Atlantic Canada. Weakening is predicted again beginning on Tuesday afternoon.

As of 11 a.m. EDT Sunday, Lee was centered about 270 miles north-northeast of the northern Leeward Islands, moving west-northwest at 8 mph. Lee was at the top of the category 2 range, with sustained winds of 110 mph and a central pressure of 958 mb. There were no advisories for any Caribbean islands, as Lee is expected to pass well to their northeast. However, large swells and rough surf were affecting north-facing coasts of the Lesser and Greater Antilles, the Bahamas and Bermuda, and will begin affecting the U.S. east coast later on Monday, and through the week.

Intensity forecast for Lee

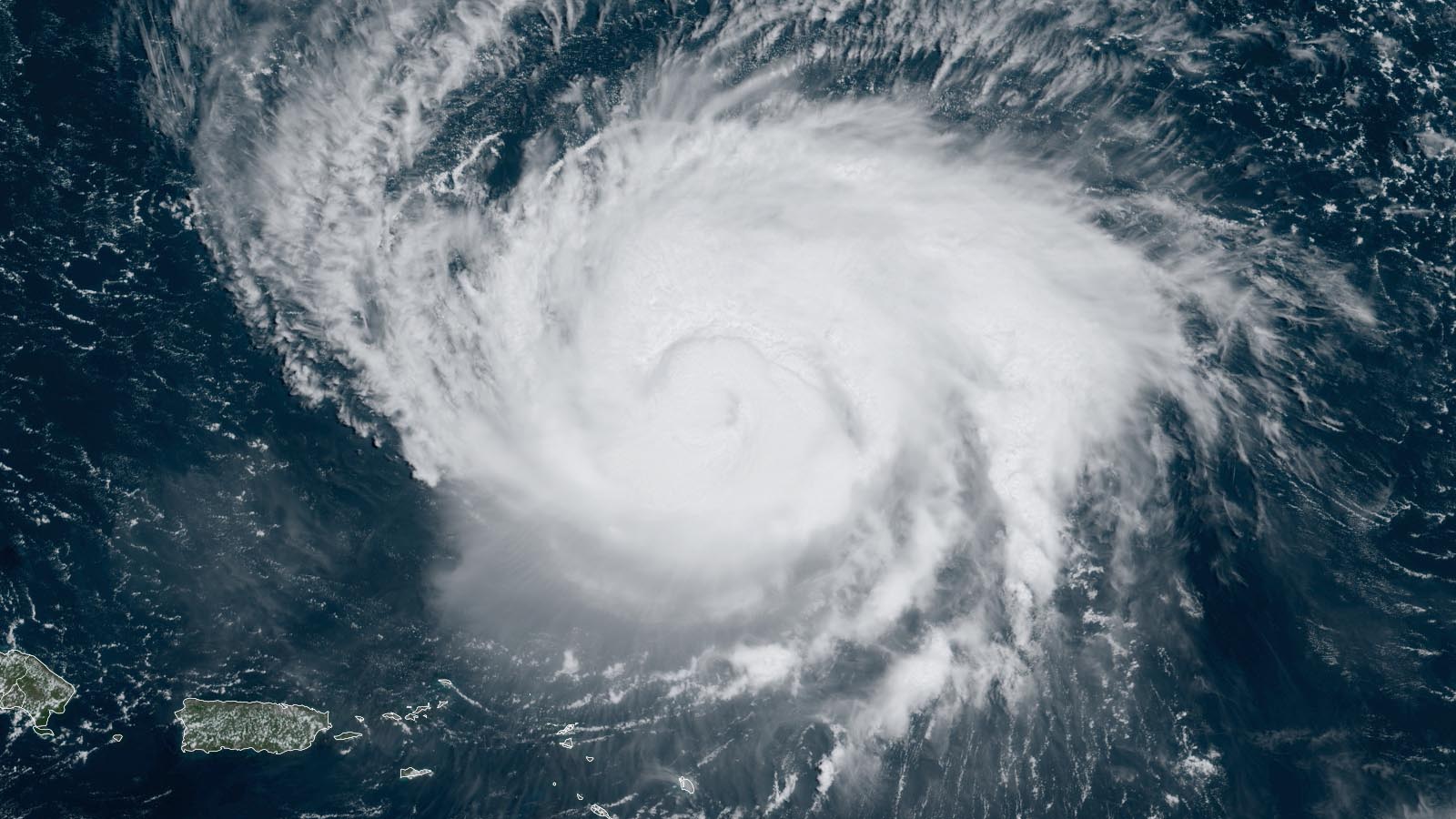

The moderate to strong wind shear (around 15-20 knots) that weakened Lee from its formidable peak as a category 5 storm with 165 mph winds on Friday was beginning to abate on Sunday, but was still keeping Lee from intensifying quickly. Lee underwent an eyewall replacement cycle on Saturday and Sunday, which decreased the peak winds of the hurricane, but spread out the storm’s winds over a larger area. Satellite images early Sunday afternoon showed a new, larger-diameter eye developing, and Lee’s eyewall growing more symmetric with colder cloud tops, indicating strengthening.

With wind shear predicted to be less of a hindrance than on Saturday, Lee is expected to take advantage of near-record-warm sea surface temperatures (around 29 degrees Celsius or 84 degrees Fahrenheit) and ample deep oceanic heat content to undergo some modest reintensification. In its forecast late Sunday morning, the National Hurricane Center predicted Lee would reach category 4 strength (130 mph winds) Monday night through Tuesday morning. By that time, Lee is predicted to be moving at a very slow forward pace of 5 mph, and the oceanic heat content along its path will be diminishing. Together, these factors will allow the hurricane to be subject to cold waters upwelled by its strong winds. This is likely to cause weakening, and further weakening is likely by Friday when Lee begins encountering the cold-water wakes left behind by Hurricane Franklin and Hurricane Idalia. Wind shear is also likely to increase at that time.

Should Lee make it to the coast of Atlantic Canada or the Northeast U.S. by next weekend (see below), it is very unlikely to be a major hurricane. Any landfall could still be high-impact, though, as Lee would likely be a very large system by that point, with a broad area of high winds and seas. Even if Lee stays entirely offshore, we can expect a prolonged period of coastal impacts along much of the U.S. and Canadian Atlantic coast later next week, including rip currents and beach erosion.

Track forecast for Lee

There is little change to the predicted track of Lee. The hurricane is expected to move west-northwest at a gradually slowing forward speed through Tuesday, passing a few hundred miles to the northeast of the northernmost Leeward Islands, sparing them any major impacts from wind and rain.

On Wednesday, Lee is expected to reach the western edge of the high-pressure ridge steering it and begin to feel the steering influence of a trough of low pressure moving over the U.S. East Coast. This trough is likely to turn Lee fairly sharply toward the north by Thursday, as predicted by NHC and depicted in Figure 1 above. This turn would keep the core of Lee away from the southeastern Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands, sparing them from any major impacts from wind and rain.

Lee is expected to make its closest approach to Bermuda Friday. Nearly all of the model ensemble members keep Bermuda on the stronger right side of Lee, so at a minimum the island will have a substantial risk of receiving tropical storm-force winds and heavy rains from Lee’s outer spiral bands. In their 11 a.m. EDT wind probability forecast, NHC gave Bermuda a 29% chance of receiving tropical storm-force winds through Friday morning.

After Lee passes Bermuda, the hurricane poses a landfall threat to the Canadian Maritime Provinces, and perhaps to the Northeast U.S. as well. The Sunday morning runs of the GFS and European models and their ensembles were showing that a landfall as far west as Massachusetts or as far east as Newfoundland remained possibilities. A recurvature out to sea prior to any landfall is also a good possibility. The most likely location for any initial landfall at this point appears to be Nova Scotia, based on model consistency, but it is too soon for any high-confidence landfall forecast a week from now.

The biggest uncertainty in Lee’s track lies in how fast the storm will be moving (see Tweet above, showing the predicted position of Lee at 2 a.m. EDT Sunday, September 17). The steering of the storm will be determined by a trough of low pressure to the storm’s west, over eastern North America, combined with a ridge of high pressure to its east. If the ridge extends far enough to the northwest, it will block Lee’s path to the east, resulting in the hurricane making landfall in the Canadian Maritime Provinces or possibly even New England next Saturday or Sunday. A weaker and/or more southerly ridge would allow Lee to recurve out to sea without making landfall, and the details of the strength and positioning of this ridge remain to be determined. It also remains unclear exactly how the eastern North American trough will evolve, as several impulses will be entering and lifting out from the trough over the next few days.

Tropical Storm Margot no threat to land

As of 11 a.m. Sunday, Tropical Storm Margot was located in the remote central Atlantic, about 1,145 miles west-northwest of the Cabo Verde Islands, headed north-northwst at 9 mph. Margot’s top sustained winds were 50 mph, and satellite images showed that the storm was struggling against high wind shear to organize. Margot is expected to reach hurricane strength on Tuesday, but is not a threat to any land areas this week. Margot may end up being a long-lived storm, but it is not expected to move anywhere near populated areas.

A new African wave has the potential to develop

A tropical wave emerging from the coast of Africa on Sunday is expected to merge later this week with another tropical disturbance (Invest 97L) located just west of the Cabo Verde Islands. This combined system may develop over the central tropical Atlantic late this week, according to the GFS and European models and many of their ensemble members. In their 8 a.m. EDT Sunday Tropical Weather Outlook, NHC gave this system 2-day and 7-day odds of development of 0% and 30%, respectively. The next name on the Atlantic list of storms is Nigel.

Mid-season check-up: How is the Atlantic doing?

September 10 marks the climatological midpoint of the Atlantic hurricane season. The first half of the season set a blistering pace for storm formation, with 14 named storms (including a belatedly recognized subtropical storm from January). The first-half average (1991-2020) of the Atlantic season is just eight named storms. There have been four hurricanes and three major hurricanes in the Atlantic, compared to the long-term averages through September 10 of 3.4 and 1.5. Accumulated cyclone energy, or ACE, was at 76.3, well above the average to date of 58.2, according to the real-time tropical cyclone statistics page from Colorado State University.

Despite the profusion of named storms, 2023 thus far has been a low-impact season for the Atlantic compared to recent years. The basin’s only major landfall thus far was Hurricane Idalia, which struck the Big Bend of Florida as a high-end category 3 storm on August 30. After higher initial estimates, it appears that insured damages from Idalia will be in the range of $2 to $5 billion, with 10 direct and indirect fatalities (total damages are typically about double insured damages). The financial hit from Idalia is far less than from each of the other eight major hurricanes that have struck the United States, including Puerto Rico, since 2017 – except for one. The exception, and a rough analog to Idalia in terms of impact, is Hurricane Zeta, which hit southeast Louisiana as a low-end category 3 storm in October 2020. According to NOAA, Zeta inflicted $5.1 billion in insured and uninsured damage (2023 USD) and led to six fatalities.

Wind shear tends to ramp up across the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean during autumn when an El Niño event is intensifying. Sea surface temperatures in the Niño3.4 region over the eastern tropical Pacific are now in the strong range for El Niño, according to NOAA. So with any luck, 2023 will be a “front-loaded” Atlantic hurricane season that peters out toward October and November – but of course, any hurricane can still be destructive and dangerous.

Website visitors can comment on “Eye on the Storm” posts (see comments policy below). Sign up to receive notices of new postings here.

Source link