Computer models predict that a large tropical wave approaching the Lesser Antilles Islands is encountering too much dry air to develop at present, but the wave will encounter a more moist and favorable environment for development this weekend near the Bahamas.

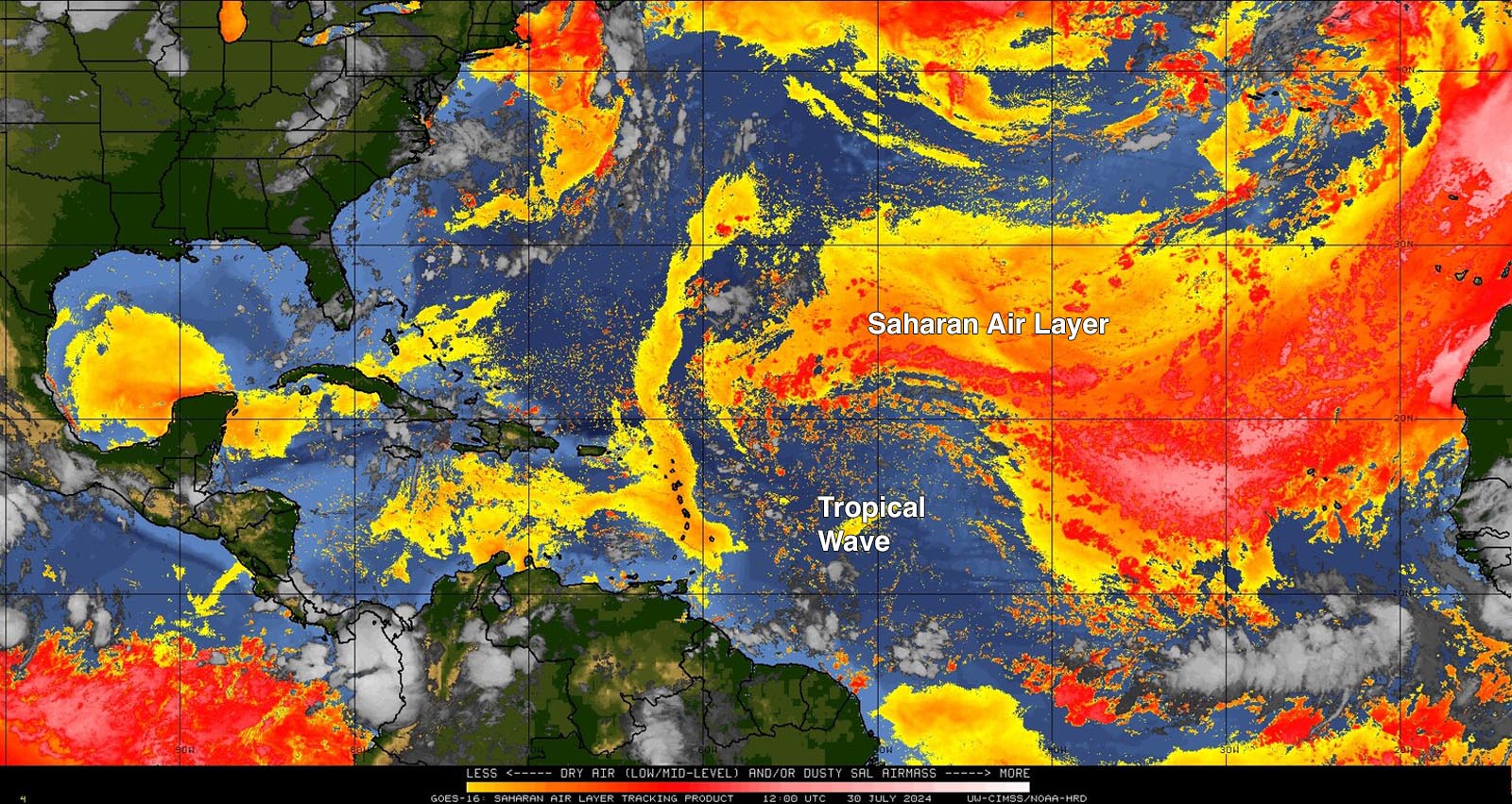

The tropical wave, which was not yet organized enough on Tuesday morning to be given an “Invest” designation by the National Hurricane Center, was centered a few hundred miles east of the Lesser Antilles, headed west-northwest at about 15 mph. Satellite imagery showed that the wave was embedded in a large region of dry air from the Saharan Air Layer, and had almost no heavy thunderstorms. Otherwise, conditions were favorable for development, with light to moderate wind shear of 5-15 knots and near-record sea surface temperatures of 29 degrees Celsius (84°F).

Forecast for the disturbance

A strong ridge of high pressure associated with the Azores-Bermuda High will steer the disturbance to the west-northwest through Friday, when it will be near the southeastern Bahamas and Hispaniola. The atmosphere is expected to steadily moisten, and with mostly moderate wind shear and near-record sea surface temperatures, the disturbance has decent model support for development on Friday or Saturday. A stronger and earlier-developing system is more likely to track to the north, passing through the Bahamas and representing a threat to the Carolinas early next week. This is the solution favored by the 0Z and 6Z Tuesday runs of the European model. A weaker and slower-developing system is likely to take a more southerly track, potentially affecting the Dominican Republic, Haiti, eastern Cuba, and Florida, then crossing into the Gulf of Mexico early next week. Disruption of the circulation by passage over the mountainous Greater Antilles Islands would slow development. This is the solution preferred by the 6Z Tuesday run of the GFS model and the 0Z Tuesday run of the UKMET model. None of the models showed the disturbance becoming a powerful hurricane over the next seven days.

By Saturday, a trough of low pressure approaching the U.S. East Coast will disrupt the ridge of high pressure steering the disturbance, pulling the disturbance more to the northwest. If the disturbance is far enough north, this trough will be capable of pulling the disturbance into the Carolinas early next week, or potentially causing the system to recurve out to sea without hitting land.

In their 8 a.m. EDT Tuesday Tropical Weather Outlook of the National Hurricane Center gave the wave 2-day and 7-day odds of development of 0% and 60%, respectively. The first hurricane hunter mission into the wave is scheduled for Thursday afternoon. The next name on the Atlantic list of storms is Debby. Based on 1991-2020 data, the average date of the “D” storm (i.e., the fourth named system of an Atlantic season) is August 15.

Tropical cyclones remain stuck on the Northern Hemisphere’s back burner

Apart from the far-flung destruction inflicted by Hurricane Beryl – the globe’s only Category 5 storm so far in 2024 – there hasn’t been much havoc produced by tropical cyclones north of the equator this year. As of July 30, according to statistics maintained by Colorado State University, the Northern Hemisphere had racked up only 64.4 units of accumulated cyclone energy. That’s just under 50% of the long-term average (1991-2020) for the date. The Northern Hemisphere has also seen only about half of the average number of named storms (9 vs. 18.2); less than half of the average named storm days (30.0 vs. 72.2); and only 3 hurricanes, compared to the average of 8.7.

Were it not for Beryl in the North Atlantic, each of the four basins of the Northern Hemisphere would be running far below their average activity, based on these numbers through July 30:

North Atlantic: 36.1 (average 9.4)

Northeast Pacific (east of the International Date Line): 1.6 (average 41.5)

Northeast Pacific (west of the International Date Line): 25.0 (average 72)

North Indian: 1.7 (average 9.5)

There’s no obvious single factor behind the hemispheric quietness. In the Atlantic, where sea surface temperatures in the Main Development Region are now warmer than their usual early-October peak, the quietude we’ve seen in mid- and late July is mainly from a persistent, widespread invasion of dry, dusty air – the Saharan Air Layer. This is typical for July. In the Northeast Pacific, seasons with a developing La Niña event, such as this year, tend to be less active than normal. Meanwhile, in the Northwest Pacific, tropical cyclone counts tend to be reduced during summers that follow a strong El Niño event, like the one that occurred in 2023-24.

We will be posting daily updates within this post.

We help millions of people understand climate change and what to do about it. Help us reach even more people like you.

Source link