Headlines

- Hurricane Beryl was “only a category one” storm, so how did it cause so many issues?

- Today’s post tries to bust the myth of “it was only a category one.”

Hurricane Katrina’s first rodeo

Back in August of 2005, South Florida was struck by a hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph. The storm made landfall near the border of Miami-Dade and Broward Counties. It killed 14 and caused the 2024 equivalent of $1 billion in damage. It was Hurricane Katrina, and while the storm is obviously remembered for the horror it inflicted on the Gulf Coast, Katrina’s first act was to catch South Florida a bit off-guard. Katrina dumped 10 to 20 inches of rain and knocked out power to about 1.5 million Floridians.

Katrina intensified from about a 50 mph tropical storm to an 80 mph hurricane in the 24 hours leading up to landfall in South Florida. By the time it re-emerged into the Gulf of Mexico, it had only lost a bit of intensity. You can view a great radar loop from Brian McNoldy’s archive here, and you can see how the storm really got its act together right at landfall.

There have been numerous category one hurricanes that have hit land over the years. Yes, most are generally well-behaved. Most cause some damage but not exceptionally long-term disruption. Katrina bucked this trend somewhat, and early this month, Beryl did the same for Houston.

During Katrina, winds gusted to 97 mph in Homestead, 94 mph in Virginia Key, 82 mph in Fort Lauderdale, and 78 mph in Miami. During Beryl, winds gusted to 97 mph just near Freeport, 85 mph in Angleton, 78 mph in Galveston, 84 mph at Hobby Airport, 83 mph at Bush Airport, and 89 mph at the University of Houston. In some ways, Katrina and Beryl make for a nice case study of like-minded category ones. And they also blow away the myth of “it’s only a category one.”

The usefulness of the Saffir-Simpson Scale

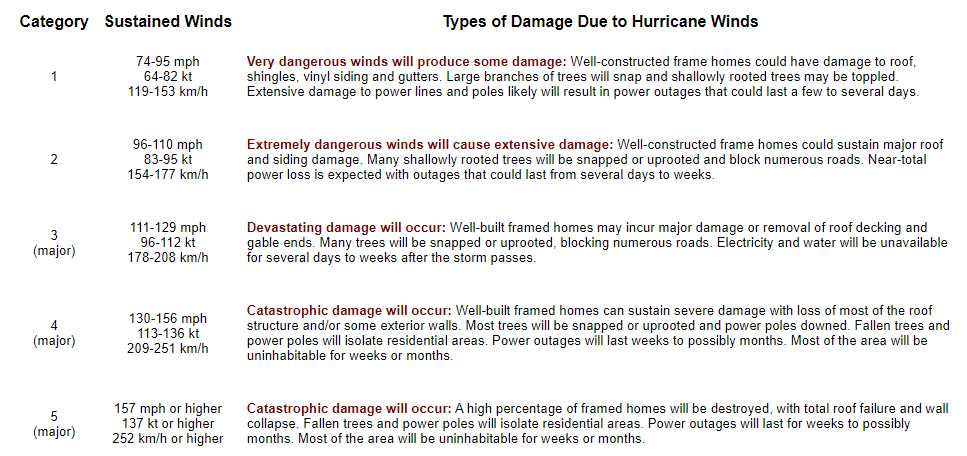

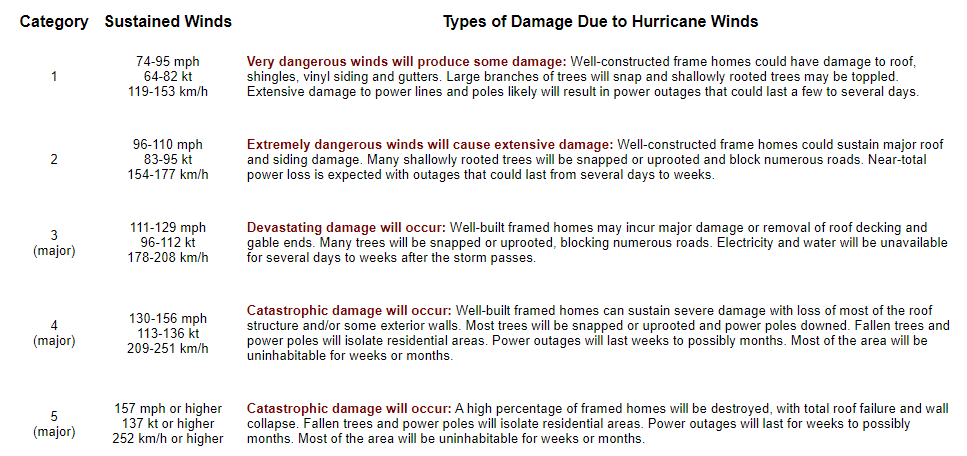

For hurricanes, we’ve long relied on the Saffir-Simpson scale to guide us in terms of the definitive categorization of intensity.

It’s a great tool for bucketing hurricanes in terms of their strength. Category 5 storms like first ballot hall of famers Andrew, Camille, and Michael generally fit the idea of the scale nicely. It tends to work even better when you consider “major” hurricanes, those that are category 3 and higher. The vast majority of memorable, devastating storms will fall into those buckets.

The uselessness of the Saffir-Simpson Scale

While the scale has true scientific value, many disparate voices within the meteorology and social science communities and beyond have long argued that the Saffir-Simpson Scale falls short in conveying the true threat to the public from a given hurricane. Think about Hurricane Harvey. It was a category 4 hurricane with massive damage on the Middle Texas Coast. By the time it arrived in Houston, it was a tropical storm, but it produced arguably the worst flooding event in Texas history. Hurricane Agnes in 1972 was only a category 1 storm but ended up being the costliest hurricane in American history at the time. The Saffir-Simpson scale, for all its usefulness is based on one variable and one variable only: Maximum sustained wind. If you have a 25 mile radius of hurricane winds that hit 155 mph winds, you have a category 4 hurricane. Whereas a storm like Hurricane Sandy before it was classified as extratropical was “only” a category 1 storm with 85 to 90 mph winds but had a wind field that sent hurricane winds out 175 miles from the center. Which storm is capable of more damage? Or are they capable of equal damage?

Thankfully, most meteorologists recognize this and tend to focus on the impacts more than the category of the storm.

Beryl came in like a wrecking ball

This brings us to Beryl. Right off the top here, let me explain some Matt philosophy for you. Prior to Beryl, Matt believed that things would generally be fine in Houston during category 1 or 2 hurricanes because once they arrived in the city, we’d have gusty winds, some power outages, and scattered damage. But overall, we’d get back up on our feet rather quickly. I even basically said as much literally a few hours before Beryl’s eyewall moved into Houston.

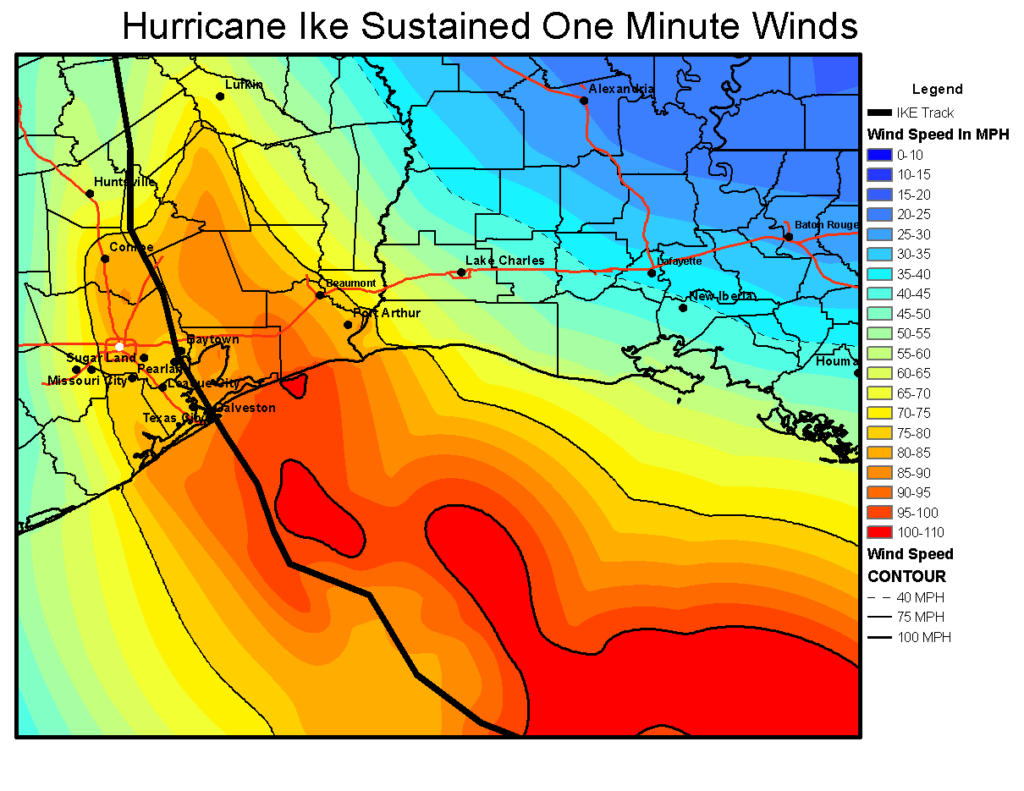

Yes, we did see the forecast 40 to 80 mph wind gusts, but it was more like 60 to 90 mph over the entire metro area. I believed we’d fare well, given that Hurricane Ike, a much larger and somewhat stronger storm in 2008 knocked out power to 2 million customers for up to 2 weeks, even though most of the Houston metro experienced the western (weaker) side. I figured, Beryl, smaller, weaker, but the dirty side…we’ll have outages and some damage, but we’ll manage.

Sustained winds were higher during Ike, but wind gusts in Beryl came up to basically match some of those sustained winds.

Here we are comparing a category 1 relatively compact hurricane to a category 2 unwieldy, large hurricane.

Why did Beryl match Ike’s scope of power outages despite being a weaker storm? First, the track put Houston on the stronger side, so most of the metro area saw the eyewall of Beryl and the strongest winds. Second, and this is where our expectations probably failed us most: Ike was weakening on approach to Texas. Beryl was entering rapid intensification. Beryl was only slightly weaker when it arrived in Houston as it was on the coast. Ike was about 110 mph at landfall and 95 mph once in Houston. Beryl was 80 mph at landfall and 75 mph once in Houston.

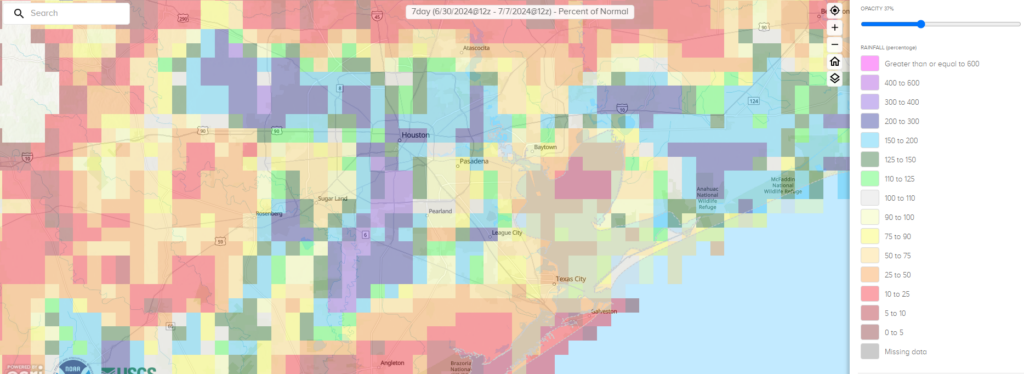

It barely weakened. Why? I think there are two reasons. First, Beryl while undergoing rapid intensification up to landfall took some time to unwind. There is absolutely a difference between a hurricane ramping up at landfall and one that is already decelerating. My new philosophy on this will be to add a category of wind impacts to a storm that is intensifying up to landfall. Second, Beryl was traveling over an area that had seen about 200 to 400 percent of normal rainfall over the prior week.

For Houston and points south, basically right on Beryl’s track, we had very soggy ground. This likely contributed both to Beryl maintaining intensity and the wind damage it caused. Trees fall more easily on saturated ground. Could there be an element of brown ocean effect at play here, where hurricanes can maintain intensity over land? Maybe, but that’s a longer-term research project.

There’s certainly an argument to be made about whether or not the power infrastructure in the Houston area is underprepared for the true threat this region faces. After Katrina hit Miami in 2005, 90 percent of customers had power back within three days. Three days after Beryl, about 58 percent of customers were back online in Houston. I don’t want to use this post to assign blame or recommend what should be done, but given that a category one or stronger storm can hit Texas every other year or so on average, this is probably an area that should be a wake up call. Texas should be attempting to match Florida, which has done great work in the hurricane resiliency space, between power restoration and building codes, despite some occasional hurdles.

Most importantly, I want this post to convey that there is honestly no such thing as “only a category one” hurricane or “only a tropical storm.” While classifying storms is good from a scientific standpoint after the fact, it’s not always great science communication in real-time. This was certainly a wake up call for me, and I hope it will be for others that the only thing that matters in each unique storm is what the impacts will be. And hopefully we can convey them in an understandable way to folks here in Texas and elsewhere as our site grows across the Gulf and Atlantic.

Source link