Hurricane Warning flags were flying in Jamaica on Tuesday as Category 5 Hurricane Beryl hurtled toward the island. Beryl blasted through the Windward Islands on Monday as a category 4 storm with 150 mph winds, killing seven and causing severe damage. On Monday night and Tuesday morning, Beryl peaked as a category 5 storm with 165 mph winds, making it the strongest Atlantic hurricane on record in July (old record: 160 mph on July 17, 2005, Hurricane Emily, the only other July Cat 5 on record). The prior record for earliest Atlantic hurricane with 165 mph winds was August 5, 1980 (Hurricane Allen).

Devastation on Grenada’s island of Carriacou

Beryl made landfall at 11:10 a.m. EDT Monday on the Windward Island of Carriacou (population 8,000), which is in the Grenadine Islands (but part of the nation of Grenada). The island is famous for its coral reefs and for its friendliness (see the poignant interviews with residents by storm chaser Jonathan Petramala in the aftermath of Beryl).

Beryl was the second-strongest hurricane ever to make a landfall in the Windward Islands, which encompass the southern half of the Lesser Antilles Islands. Only Hurricane Maria’s September 19, 2017, landfall on Dominica (the northernmost of the Windwards) as a Category 5 storm with 165 mph winds was stronger.

Damage was heavy in Carriacou. Ground-based and drone videos from WXChasing (see below) showed widespread severe wind damage, with a few areas of catastrophic damage. Structures at higher elevations on hills, where winds were likely up to 30% higher, suffered the most. Storm surge damage appeared modest along the coast where the drone flew, which was on the northwestern (lee) side of the island, which did not get a direct storm surge. No official wind measurements are available for Beryl’s landfall in the island, but at Maurice Bishop International Airport on the southwest end of Grenada (elevation 22 feet), which lay just south of Beryl’s weaker southern eyewall, had peak sustained winds of 92 mph, gusting to 121 mph.

Beryl’s center passed about 90 miles to the south of Barbados on Monday morning, and the island’s Grantley International Airport recorded peak winds of 52 mph, gusting to 69 mph, at 9:14 a.m. AST (equivalent to EDT). Considerable storm surge damage occurred on Barbados (see video below), sinking at least 20 boats.

At Maurice Bishop International Airport on the southwest end of Grenada, winds as of noon AST were sustained at 92 mph, gusting to 121 mph. Even higher winds likely occurred on the north side of Grenada, just beyond the southern eyewall of Beryl. Heavy damage occurred over much of Grenada, with over 95% of the nation losing power. Damage was also reported in St. Lucia, well north of Beryl’s core, and in Venezuela, well to the south.

Beryl weakening

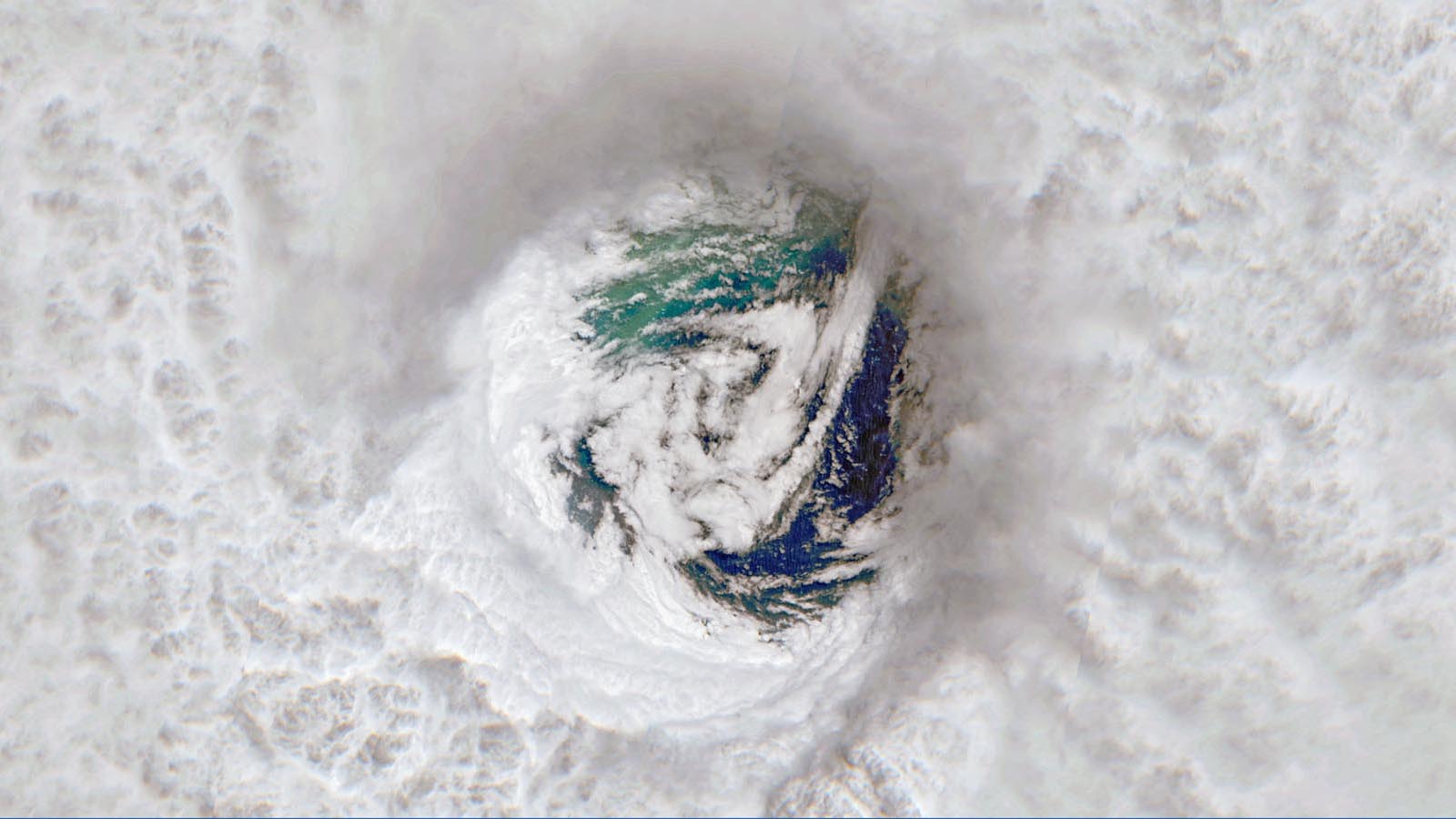

At 11 a.m. EDT on Tuesday, the Hurricane Hunters had found that Beryl had weakened slightly, but was still a category 5 storm with 160 mph winds and a central pressure of 938 mb. The hurricane was located 555 miles east-southeast of Kingston, Jamaica, headed west-northwest at 22 mph. The Hurricane Hunters noted that the eyewall of Beryl now had a gap in it, and the western eyewall was beginning to erode, indicating that increased wind shear was beginning to take a toll on the storm. Shear effects were already apparent on Tuesday morning satellite imagery, which showed a more asymmetric cloud pattern and warming of the cloud tops.

A significant blow to Jamaica is a strong possibility

A strong ridge of high pressure to the north of Beryl, typical for July, is expected to keep the hurricane moving west-northwest at 15-23 mph through Friday. This track would take the hurricane over or just south of Jamaica on Wednesday, just south of the Cayman Islands on Thursday morning, and into Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula on Friday. The official NHC track forecast has outperformed all individual models so far, and Jamaica lies along the northern side of the latest NHC cone of uncertainty, making a direct hit by Beryl on the island a strong possibility.

A number of the 6Z Tuesday forecasts from some of our top track models predicted a Wednesday afternoon landfall in Jamaica, including the European and GFS models. According to model verification stats posted at Brian Tang’s website, the best track model thus far has been the HAFS-A; the 6Z Tuesday run of that model predicted that Beryl would make landfall on Wednesday afternoon along Jamaica’s south coast, west of Kingston, then pass about 70 miles south of Grand Cayman Island on Thursday morning. Any track near or just south of the coast could propel a predicted 5-8 feet of maximum storm surge toward Kingston, the largest city in Jamaica. Heavy wind damage will be a major concern on the island, particularly in Jamaica’s many hilly areas, where wind speeds may be increased by up to 30%. Heavy rains causing flash flooding and mudslide are also a major hazard (Fig. 1).

Three-day intensity forecast for Beryl

Beryl’s intensity when it makes its closest pass to Jamaica is highly uncertain, with the models predicting the hurricane will be between category 2 and category 4 strength. Strong upper-level winds out of the west increased overnight, and were creating a moderate 15-20 knots of wind shear for Beryl on Tuesday morning. In addition, Beryl will soon encounter stronger mid- and low-level shear associated with how the geography of the Caribbean affects the strength of early-season trade winds, as explained well by Eric Webb on social media. These multiple shear effects are predicted to continue through Friday, with high confidence they will soon cause a steady weakening.

Beyond Wednesday, if Beryl passes close enough to Jamaica, the high mountains of the island may significantly disrupt the hurricane’s inner core, resulting in substantial weakening. Conditions will otherwise be favorable for the hurricane until landfall Friday in the Yucatan Peninsula, with record-warm waters near 29 degrees Celsius (84°F), a high ocean heat content, and a moderately moist atmosphere. NHC predicts that Beryl will reach the Yucatan Peninsula as a Category 1 hurricane, but there is substantial uncertainty in this intensity forecast for the reasons above.

Long-range outlook for Beryl

Passage over Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula on Friday will weaken Beryl, and the hurricane is likely to emerge into the Gulf of Mexico on Saturday as a tropical storm. At that time, Beryl will be to the southwest of the center of the ridge of high pressure steering it, and the clockwise flow of air around that high will turn Beryl more to the northwest, resulting in an eventual landfall along the coast of northeastern Mexico or Texas early next week. Long-range wind shear forecasts are not very reliable, but current indications are that Beryl will have low enough wind shear to allow intensification into a category 1 hurricane before this final landfall, as it passes over unusually warm waters for early July (1-2 degrees Celsius or 1.8-3.6 degrees Fahrenheit above average).

Jamaica hurricane history

The most recent hurricane to impact Jamaica was Hurricane Sandy (2012), which killed one person and did $20 million in damage (2023 USD), according to EM-DAT. The most destructive hurricane in Jamaican history was Hurricane Gilbert (1988), which killed 49 and cost $2.5 billion (26% of GDP). A 2018 retrospective from NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic & Meteorological Laboratory includes background on hurricane-hunter flights and related research on Gilbert, which was analyzed with the lowest surface pressure (888 mb) of any Atlantic hurricane up to that point. (Jeff Masters, lead author of this post, was the flight director on the hurricane hunter mission that measured that pressure, and he took the picture in Fig. 4). Jamaica’s deadliest hurricane was a 1912 hurricane that killed 142. According to independent hurricane researcher Michael Chenoweth, there are no records of hurricane-strength winds having occurred in Jamaica any earlier in the season than July 31.

The top five most damaging Jamaican hurricanes (in 2023 USD, according to EM-DAT):

1) Gilbert, 1988, $2.5 billion

2) Ivan, 2004, $920 million

3) Charlie, 1951, $630 million

4) Charley, 2004, $470 million

5) Dean, 2007, $420 million

Beryl is Earth’s first Cat 5 storm of 2024

With the rest of the Northern Hemisphere tropics unusually quiet so far this year, Beryl is Earth’s first Cat 5 storm of 2024. This year is well behind the pace of 2023, when the planet experienced nine category 5 storms (using ratings from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center and National Hurricane Center). The 1990-2022 average globally for an entire calendar year is 5.3 Cat 5s, so 2023 was well above average, tied for third-highest since 1990, whereas 2022 was well below average, with only two Cat 5s. The record is 12 Cat 5s in a year, set in 1997. The strongest Cat 5 of 2023 was Super Typhoon Mawar in the Western Pacific, which peaked with 185 mph winds in May.

If one looks at the number of category 5 storms that have occurred since 1982—the year most commonly used in the scientific literature to begin the study of global tropical cyclone trends—there has been a noticeable increase in Cat 5s. According to a 2020 review paper by 11 hurricane scientists, “Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change Assessment: Part II: Projected Response to Anthropogenic Warming”, the proportion of global tropical cyclone that reach category 4 and 5 strength is likely to increase as the climate warms, with 8 of 11 authors rating this as medium-to-high confidence and three authors rating it as high confidence. The median projected change for a 2°C warming above pre-industrial temperatures was +13%. However, the experts had a very mixed view of whether or not the actual number of global Cat 4 and Cat 5 storms would increase, since most model studies show a decrease in the total number of tropical cyclones that will occur in a warmer climate. A 2022 paper by Chand et al., Declining tropical cyclone frequency under global warming, showed that this decreasing trend in the total number of global tropical cyclones may already be observable.

96L struggling with dry air

A tropical wave designated Invest 96L is speeding westward across the tropical Atlantic at 15-20 mph, and will bring heavy rain showers to the Lesser Antilles Islands on Wednesday.Satellite images showed that 96L struggling with dry air, and had a meager area of heavy thunderstorms with poor organization.

Dry air will continue to plague 96L this week, and the system is no longer likely to develop. In their 8 a.m. EDT Tuesday Tropical Weather Outlook, the National Hurricane Center gave 96L two-day and seven-day odds of development to 20% and 30%. The next name on the Atlantic list of storms is Debby.

We help millions of people understand climate change and what to do about it. Help us reach even more people like you.

Source link