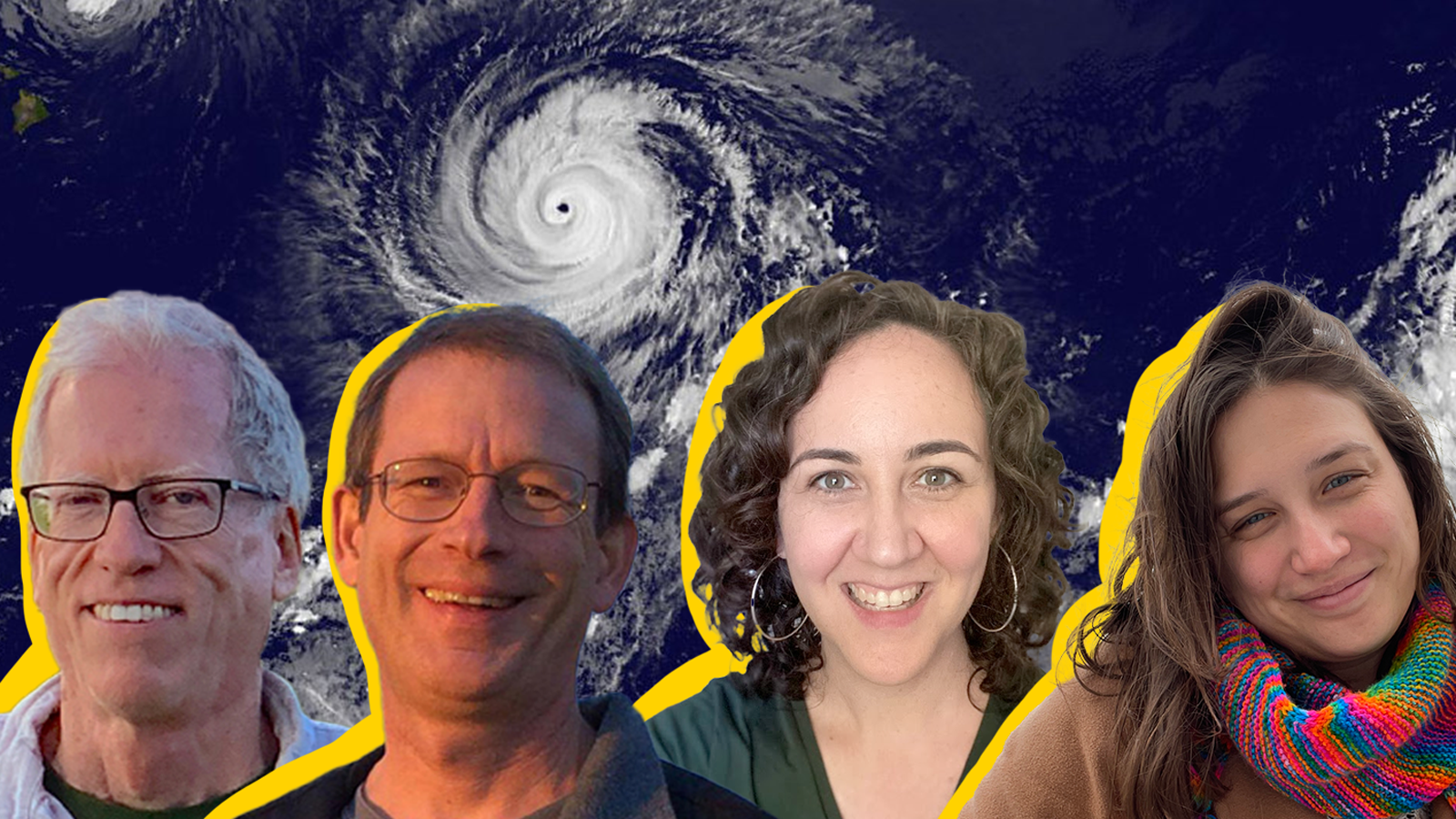

To kick off hurricane season, Yale Climate Connections editors Sara Peach and Sam Harrington sat down with meteorologists and Eye on the Storm writers Jeff Masters and Bob Henson.

This roundtable discussion has been edited and condensed.

Sam: What is your process of covering a hurricane?

Jeff: It kind of starts on Twitter or Bluesky now. Some of the aficionados of hurricane forecasting are anticipating, well before the National Hurricane Center puts something out, that “Hey, this is something we got to watch.” And of course, Bob and I look on our own at the models and see just kind of the general pattern, how things are shaping up. It can give you a general feel for something that might be coming up.

Bob: Yeah, I think there’s more and more skill with identifying busy periods. Even if the individual hurricanes aren’t ironclad, the models will give us a sense of maybe a particular week might be busy. So we try to keep an eye out for busy periods.

Jeff: Yeah, I’ll adjust my vacation schedule, depending on what the models are showing. I mean, I like to go up north and go camping near Lake Superior. And I’ll try and come up with a four- or five-day stretch that’s not going to see a major landfalling storm, according to the latest model guidance.

This year, it could be an early hurricane season.

Sam: Is that what it’s feeling like to you?

Jeff: It’s nuts. The ocean temperatures are at August levels, when you talk about the total heat content of the ocean. So something could pop early this year — better-than-average chances of a major hurricane coming early in the season.

Read: What you need to know about record-breaking heat in the Atlantic

Bob: I would submit also perhaps a better-than-usual chance of a late hurricane with La Niña conditions really settling in. La Niña years can often have some really bad late hurricanes.

Jeff: That’s a good point. The end of the season could be more active than the early part of the season in that regard.

Bob: That was the case in 2020, when we went all the way into the supplementary names.

Jeff: It never wanted to stop. 2005, same thing. I mean, I was blogging on New Year’s Eve. And I’m like, “This is insane. What am I doing here? I’m gonna go drink some champagne. I’m out of here.” But I was blogging at a half hour to midnight on New Year’s Eve because we had an Atlantic storm in 2005. That was the height of insanity.

Bob: You could even feel the exhaustion in the discussions being written by forecasters at the National Hurricane Center. They weren’t hiding it much at that point.

Sam: Do you guys have a sense of why the ocean is so warm right now?

Jeff: We have a good sense. But also we have a profound mystery as to why it is so warm. And my thought is that it’s probably going to sink back down to more normal-ish levels like we expect with climate change boosted by El Niño or modified by La Niña. But we don’t know that for sure. We’re in unexplored territory now.

Bob: Yeah, I think the real question, as Jeff alluded to, is why did this particularly intense surge of record oceanic warmth happen in 2023-24, instead of 2021-22, or 2017-18, or some other recent period? Obviously, greenhouse gases are accumulating year over year. There are lots of legitimate questions as to why these surges happen when they do amid that longer-term warning. But as I understand it, the North Atlantic is sometimes at its warmest in the spring after El Niño. So this is certainly consistent with that. And there’s a lot of inertia in the oceans, too. It takes a while for them to heat up and to cool down.

Jeff: I think part of what we’re seeing is we had some very unusual atmospheric circulation patterns in 2023 that contributed to this record warming of the Atlantic ocean waters. And those circulation patterns, I think, are probably one-offs and are not likely to repeat. Part of it was caused by the sloshover from a three-year-long La Niña event to a strong El Niño. That was a really rapid transition from one extreme to the other. And so that weirdo circulation pattern is probably something we’re not gonna see very often and thus, things should get back into the more normal-ish. Well, the new, accelerating normal. There is no new normal. There is only more extreme, but not so extreme as what we’ve been seeing.

Bob: There are a couple of wildcards that we’ve written about in the last year or two. One of them is the undersea volcanic eruption, Hunga Tonga. That injected vast amounts of water into the stratosphere, I think adding like 20% of the total volume of water at some heights, and that may have helped exacerbate ocean warming, although probably it’s a relatively minor player. The other is the major ramp-down of particulates from ocean vessels, especially in the North Atlantic.

Jeff: But that started well before 2023. So we would have seen an effect earlier, one would think.

Bob: Exactly. This gets to the point of “Why is it happening now?” But yeah, that really kicked off in 2020, the new rules on sulfate emissions. So anyway, as always, there are multifactorial things going on, but it’s warm out there. Even the warmth of 2023-24 is within the range of what models predicted could happen when you combine long-term warming with things like El Niño.

Sam: I’d love if you all could talk a little bit about why hurricane coverage feels important and what you enjoy about it as well.

Bob: It’s good you’re asking us this in May instead of in October!

Jeff: Yeah. You know, people are interested in storms. Storms are exciting, they’re photogenic, and they’re canaries in the coal mine as far as climate change goes. So yeah, we should be paying attention to them for all these reasons. And this is now my 20th year blogging about hurricanes. I mean, the very first thing I started doing when I was blogging back in 2005 was talking about hurricanes.

Bob: This is my 10th year since I came on board at Weather Underground with Jeff in 2015.

Sam: When did climate change start to become more of a topic of conversation among people paying attention to hurricanes?

Jeff: Well, 2005. I mean, we had Katrina, and Rita, and Wilma. So it started right away.

Bob: I’ve maintained for years that there will always be a role for human beings to use relatively accessible language to keep people updated on the weather. At this point AI could do 90% of what you would see in a normal TV weathercast, but people still want that person. And I’d like to think Jeff, and I can do that, especially since we’ve been doing it for so long, and people know our voices.

It’s always fascinating and always challenging to figure out what to focus on in any given post. Sometimes it’s obvious if there’s a major hurricane bearing down on the United States, but a lot of times, there are multiple incipient threats. We try to work in climatology, and history when relevant, and that’s always fun. I love digging into history. I also really appreciate our loyal reader community and the commenters that have been following us for years.

We are also stoked that we now have Pearl doing the Spanish translations.

Sara: Us, too.

Sam: Especially when there was Otis in Mexico last year. It’s great to be able to get that information out there.

Bob: Well, Otis was an example of where things can just turn on a dime, and the forecast can look so different a day later.

Sam: How do you guys factor the increased potential for rapid intensification into how you approach storm coverage?

Jeff: We always have our evergreen posts on how climate change is affecting rapid intensification to reference. So we’re always ready to try and fit in the latest example of that phenomenon with what we expect to see with climate change and what we have seen in the past. That’s one of my big interests. I am here to put the current extreme weather event into context. How does it compare with the past? And will we be seeing more of this in the future?

Bob: Yeah, what Jeff said.

Sara: From my perspective, I just think it’s so important for people’s safety and plans for the future that they understand that the whole system is shifting in a way that’s becoming more dangerous and more extreme. And Jeff and Bob do such an incredible job of giving people that context: It’s not just the storm coverage of here’s what’s happening, hour by hour, but it’s the big picture of what we should be thinking about.

Sam: You mentioned you get into October and you feel a lot of burnout. I wonder how you guys approach that? What tools have you built up over the decades that you’ve done this?

Jeff: Certainly my daily hour of meditation and hour of exercise are essential. And as I grow older and wiser, I realize that it’s not as important to try and cover every single extreme weather event, because you simply can’t. So you just shrug and say, “Well, it’d be nice to cover that too. And it’s not going to happen because I value my mental sanity.” So you just let some things slip by that you didn’t use to let slip by. And I’m cutting down on the number of interviews I do. That helps a lot.

And this summer, I really would like to focus on some of the other extreme weather events besides hurricanes. We always have heat waves to talk about, extreme precipitation events. Sometimes there’s, you know, more severe weather tornado events to talk about. And of course, the latest science. They’re always putting out papers at inconvenient times. I mean, come on! Don’t publish something in August or September. *Everyone laughs*

I’m thinking very seriously that this hurricane season is going to be one where I’m really going to step back and not cover every single storm and mostly try and focus just on the ones that have the potential to get their names retired. So if we indeed get 33 named storms, like the University of Pennsylvania group’s talking about, you’re not going to see me have a byline about all 33 of those.

Bob: I take lots of walks and that does a lot to clear my brain. Sometimes I’ve written pieces of posts in my head literally on walks, or even sitting in a hot tub at the gym. I also sometimes will do short trips, either to see family or friends, and will just work from wherever I am. You know, that’s the beauty of remote work and laptops. And I’m very much a coffee shop hound. I tend to spend an hour or two in the coffee shop on many days. So I’ll often either start or end a post there. Or I might hand it off from home to Jeff to take a look at and then make my way to the coffee shop and then check back in. It’s only about 15 minutes away, my favorite spot.

Jeff: Last year for the first time ever, I did not take my laptop with me in the summer to some of my camping trips I did up north.

Bob: There is what I affectionately call the Masters Vacation Effect.

Jeff: It’s a fact. It’s a proven fact. When I announce I’m going on vacation, something new is gonna pop up.

Bob: Jeff going on vacation is a little like [the Weather Channel’s] Jim Cantore rolling into town.

Sam: Early warning system.

Jeff: Yeah, definitely Fear Factor five.

Bob: Jeff mentioned the University of Pennsylvania forecasts. I don’t know Sara, or Sam, if you saw that, but they’re predicting a range of they’re predicting I think 31 …

Jeff: 33 is the best guess.

Bob: … but a range of 27 to 39 storms.

Sara: That is horrifying.

Bob: That would go almost through the supplementary list!

Jeff: That would be half of the world’s activity in just the poor Atlantic basin.

Sara: What happens if they run out of supplemental names?

Bob: That’s a fantastic question. Well, we’d have to have 43 to do that.

Jeff: They would probably go Greek again. I don’t know.

Bob: And in fact, they’re going to start the regular outlooks now on May 15. They’re kind of tiptoeing toward broadening the season, it feels like. So it’s definitely “fasten your seat belt” time.

We help millions of people understand climate change and what to do about it. Help us reach even more people like you.

Source link