Transportation is the largest source of greenhouse gases in the United States, and passenger vehicles — the cars most Americans rely on to meet their daily needs — account for more than half of transportation emissions.

Conversations about reducing these emissions typically focus on electric vehicles. But increasingly, government officials across the country are aiming not just to get Americans into different kinds of cars, but to radically reduce the need to drive in the first place.

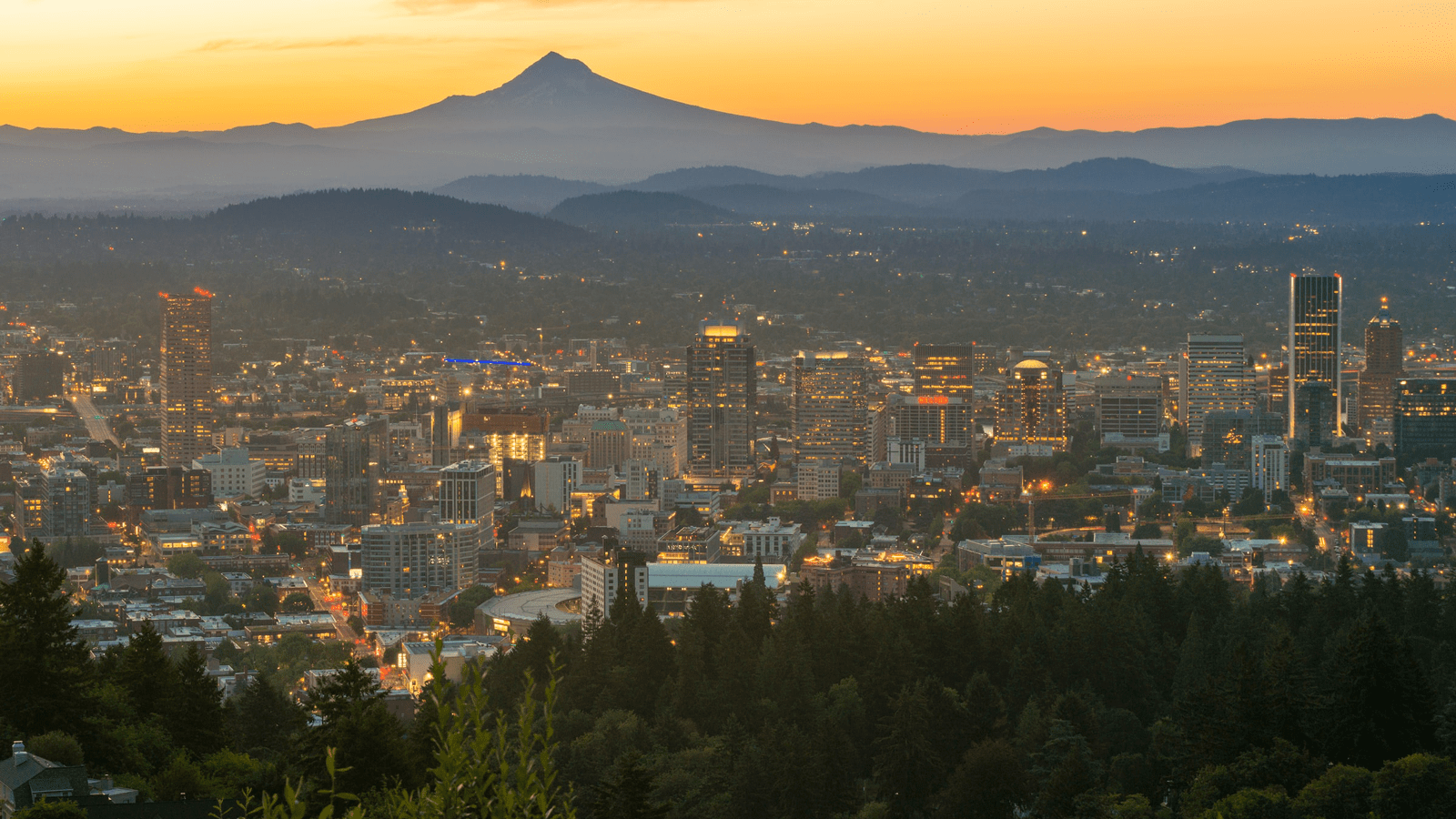

Oregon is at the vanguard of this movement. In 2020, when the state’s ambitious climate goals ran up against stubbornly high car emissions, Democratic Governor Kate Brown charged state officials with finding a solution. One initiative to emerge from her executive order is Climate Friendly and Equitable Communities, a set of urban planning rules adopted in July by the state’s Land Conservation and Development Commission.

The new rules aim to create denser communities that offer a variety of transportation options, making it easier for residents to meet their daily needs without driving. Among the requirements: local governments throughout the state must allow taller buildings in designated areas, reduce the number of parking spaces required in new developments, and provide more resources to support walking, cycling, and public transportation.

“Legalizing the ability to live and work closer together, and have cities be able to develop in this walkable way that they used to 100 years ago is a really big step forward,” said Catie Gould, a climate and transportation researcher at Sightline Institute, a think tank focused on the Pacific Northwest. The parking reforms in particular remove critical barriers to sustainable development, she said.

Gould cites Portland’s Northwest District, which was first developed in the 1800s, as an example of the kind of streetscape the new regulations aim to create. “The Northwest District has never had parking requirements. It has a lot of older brick mid-rise residential buildings. It’s a very walkable neighborhood,” she said. “I have friends that love living in Northwest, and they love all the places they can walk to, having grocery stores and restaurants and shops nearby.”

A growing trend

Driven by concerns over climate change, affordable housing, and social justice, other states and cities across the country are also enacting significant land use reforms.

In the past few years, California and Maine have effectively eliminated single-family residential zoning; other states, including Republican-led Nebraska and Utah, have made similar proposals. In October, California eliminated minimum parking requirements near public transit.

Meanwhile, local governments are using zoning to address a wide variety of issues. Minneapolis made headlines around the nation in 2019 by eliminating single-family zoning, and other cities have followed suit. Coastal communities like New York City and Norfolk, Virginia, have adopted new codes aimed at increasing resilience. These trends are being seen also in small communities like Carrboro, North Carolina, which banned new drive-through windows in its city center.

An under-the-radar solution

But while these measures have important implications for greenhouse gas emissions and climate adaptation, many of them don’t even mention the environment. As a recent Harvard Law Review article noted, discussions surrounding recent state-level reforms have largely avoided mention of climate change, focusing instead on affordable housing.

The failure to connect the dots between land use and climate change is hardly confined to these examples. Consider Evan Manvel, a climate mitigation planner in Oregon’s Department of Land Conservation and Development, who helps lead the Climate Friendly and Equitable Communities initiative. Even among colleagues, he sometimes must explain why land use reforms should be a priority when other climate solutions — electric vehicles, for example — are much better known. (His response: Since it will take decades to transition the entire fleet, and since much of the energy used to power electric cars still comes from dirty sources, EVs alone won’t cut it.)

Land use is “in some ways a more complex and less direct and longer-term tool to take on climate pollution than some of the things we’ve traditionally done,” Manvel said. “I think it’s harder to see how exclusionary zoning and other land-use decisions have caused pollution — and you see pollution coming out of a smokestack at a coal plant.”

Some legal thing … and ‘a niche concern’

Land use policy’s role in climate solutions has been obscured by its bureaucratically byzantine nature.

In the United States, land use decisions are largely made by local zoning boards; state-level interventions are a relatively new phenomenon. Zoning codes vary by municipality, leading to a mind-boggling volume of extremely specific rules across the country.

“Within a single jurisdiction, the zoning code can be a couple hundred pages long — so it’s regulating minutiae,” said Jonathan Rosenbloom, a professor at Albany Law School and the director of Sustainable Development Code, a research and editorial platform focused on planning best practices. “But then we have to compound that by 39,000 local governments across the United States. So the complexity of talking about zoning gets really difficult really fast, because we have many iterations of it, and we have many different things that it’s regulating.”

Sonia Hirt, dean of the College of Environment + Design at the University of Georgia, said that while interest in zoning has grown dramatically since she started writing a book on the topic a decade ago, it remains a niche concern.

“When’s the last time anyone talked to you about zoning at the dinner table?” she asked. “It seems like something technical and just an instrument — it’s some legal thing, and who cares? But the truth of the matter is that it’s very influential because it allows you to live a certain way, or not live a certain way.”

For example, many cities’ zoning codes specify that the only new construction type permitted in residential districts is detached single-family housing: no apartment buildings, townhouses, or other housing types, let alone grocery stores, doctors’ offices, or other commercial uses. What’s more, these codes often require that new homes meet or exceed certain requirements for square footage and lot size.

These rules, referred to as exclusionary zoning, effectively bake in sprawl. Rooted in a long history of racial, socioeconomic, and religious discrimination, they push local residents into a car-dependent lifestyle by making everyday activities — visiting a community center, eating out, going to the gym — virtually impossible without driving.

And exclusionary zoning is only one example of the myriad ways that land use policy shapes Americans’ everyday lives while impacting greenhouse gas emissions.

“Anytime you step out your door, or even anytime you move inside your own house, many of the things that are affecting how you move about your day, what you eat, how you eat it, where it comes from, what transportation you take, whether your lights are fueled by solar or wind or gas or oil — all those things are impacted by zoning,” said Rosenbloom.

Rethinking zoning’s legacy

The familiar low-rise, car-centric communities found across much of the United States can make the American land use paradigm seem natural, almost predetermined. But in fact, there’s nothing inevitable about it, according to Hirt.

“We kind of made up the system over the last hundred years, and now it’s become so customary to us that I think we just don’t really think about it,” she said.

She points to Europe to demonstrate how things might have turned out differently. Municipal zoning was born in Europe in the late 1800s, then imported to the U.S. around 1900. Within a few decades, the American model evolved crucial differences. To this day, compact districts with a mix of building types — a common formula in Europe — are less likely to be allowed under American codes. Instead, U.S. zoning is much more likely to dedicate large swaths of land to single uses: residential, commercial, or industrial.

In particular, the U.S. places unusual emphasis on single-family residential districts. In some jurisdictions, more than 90% of land is dedicated to detached single-family homes. “That really sets apart American zoning from the way it’s practiced in other countries,” Hirt said.

Legalizing traditional communities

According to Oregon’s Evan Manvel, many of the land use reforms now being enacted are essentially a return to the days before 20th-century zoning innovations reshaped the American landscape. “A lot of this is reinventing the wheel of traditional housing types that we made illegal,” he said.

But he emphasized that these changes also align with contemporary demographic shifts that have increased demand for less-expensive homes in denser, more walkable neighborhoods. “Fifty years ago, it was nuclear families, and that was 40% of households. And now it’s about 20% of households, and almost a third of households are single-person households,” he said.

He believes that the tangible benefits land use reform can bring to people’s everyday lives offer a powerful incentive to make it part of the standard climate solutions toolkit.

“It’s better housing choices. It’s the ability to walk to get your groceries. Or being able to not chauffeur your kids everywhere, and they can bike to a neighbor’s,” he said. “So hopefully, the co-benefits of working on land use will really help move it forward as a way to also reduce climate pollution.”

Source link