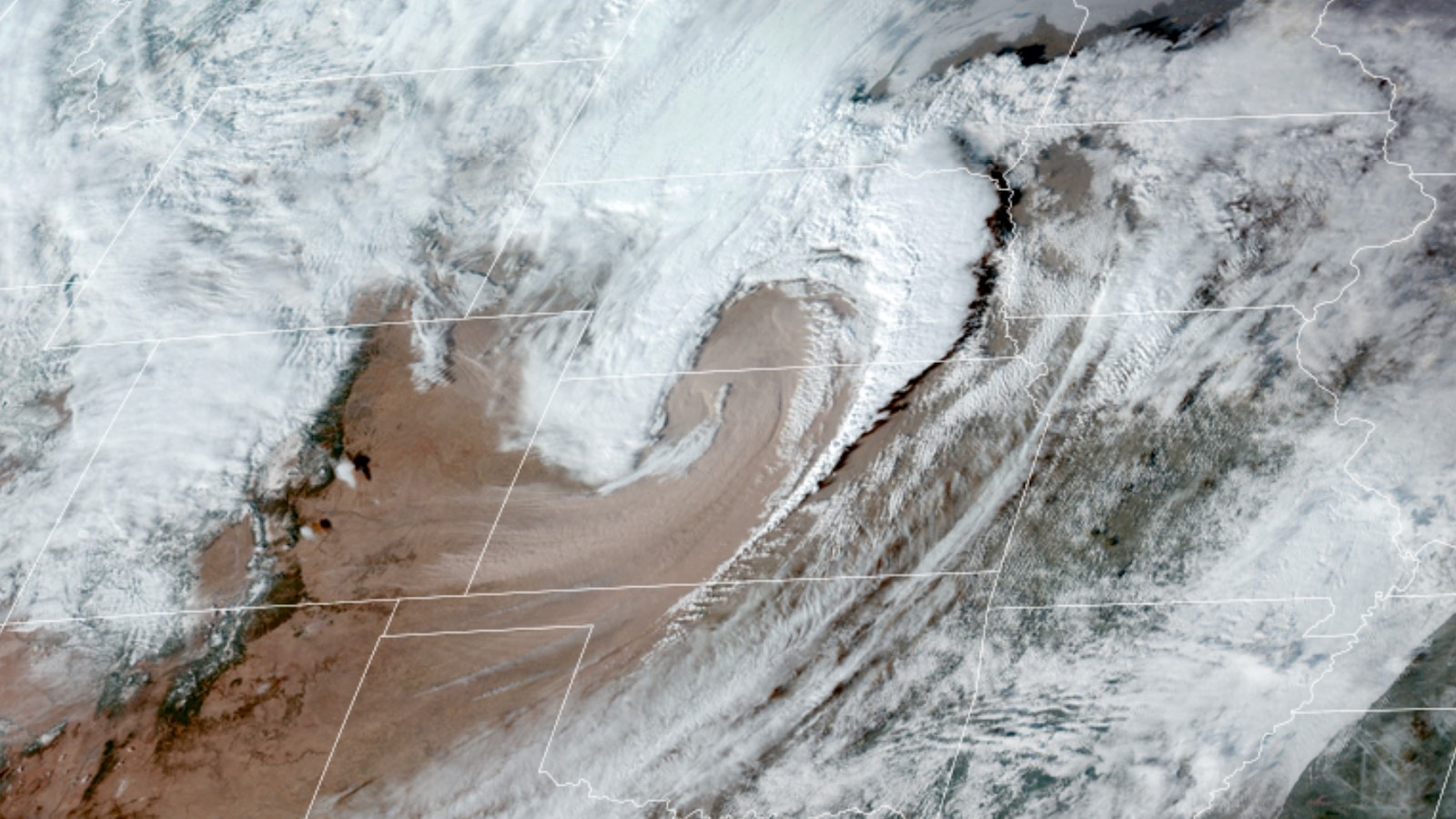

One of the most spectacular and unseasonable U.S. storm systems in memory barreled through the center of the country on Wednesday at dizzying speed. The springlike cyclone left a trail of damage that was startlingly widespread, though fortunately not nearly as catastrophic as the Mississippi Valley tornadoes of Friday, December 10 (see below for an update).

Unlike most such rapidly intensifying cyclones over the Great Plains, there wasn’t much extreme precipitation with this one. Instead, wind, warmth, and dust were the chief features, all playing out in panoramic fashion.

The storm system fed off the large-scale contrast in place during much of this autumn and early winter between frigid air toward northwest North America and recurrent unusual warmth across much of the United States. An upper-atmosphere disturbance flowing along the powerful jet stream between these areas intensified as it rolled across the Great Plains on Wednesday.

The broad contours of the setup weren’t all that unusual. Instead, it was their almost-ludicrous intensity that made Wednesday such a memorable day for weather watchers around the world, not to mention forecasters and everyday people in the midst of it all.

A sampling of Wednesday’s extremities

High winds rolling off the Rockies. The front left the mountains with a bang on Wednesday morning, as a massive line of squally winds peppered with rain and snow showers pushed into eastern Colorado and New Mexico. Winds gusted to 101 mph at Manitou Springs, Colorado, and the nearby U.S. Air Force Academy.

Blinding dust and more triple-digit wind. As the front hit the drought-stricken southern High Plains, a “sting jet” of powerful winds descended toward the south side of the surface low, pushing vast volumes of blowing dust across the Plains, especially over eastern Colorado and western Kansas.

Winds gusted to 107 mph at Lamar, Colorado, and to 100 mph at Russell, Kansas. All in all, Wednesday produced more reports of wind gusts topping 75 mph than any day on record, according to the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center (SPC).

Fast-spreading wildfire. A few wildfires erupted, but it’s fortunate there were no pre-existing fire lines of any notable size that the wind could strike perpendicularly. Instead, the blazes that popped up were like strings of fire, stretched along the wind vector. One fire in Oldham County west of Amarillo, Texas, spanned 3,500 acres along a ribbon 14 miles long and just a half-mile wide.

Stunning warmth for the season. Many dozens of locations almost certainly set record highs for December 15, and more than a few also smashed records for any date in December. These records only add to the avalanche of warmth for the month, which already included more than 3,000 daily record highs and 630 monthly record highs as of December 8.

At least two states set December records, based on preliminary data and background from Christopher Burt and Maximiliano Herrera:

—Wisconsin: 72°F at Boscobel (old record 70°F at Kenosha and West Allis on December 5, 2001)

—Iowa: 78°F at Oskaloosa

A disorienting December squall line. A narrow line of thunderstorms formed in south-central Nebraska and north-central Kansas; within hours, it had ripped into Wisconsin, sometimes traveling at more than 100 mph.

Even the Upper Peninsula of Michigan ended up in a severe thunderstorm watch, its first in December in at least the past 16 years.

The NOAA Storm Prediction Center reported at least 20 tornadoes in storms along the squall line. They appeared to be mostly smaller and short-lived, causing relatively minor damage.

How much was climate change involved?

Every weather event today plays out in a global atmosphere profoundly affected by human-produced greenhouse gases. Some types of extremes are more closely tied than others to the warming atmosphere.

In the growing field of climate change attribution, researchers analyze a particular event and attempt to determine how much its likelihood was boosted (if at all) by human-caused climate change. Two of the main outlets for attribution research are the Explaining Extreme Events from a Climate Perspective series, in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, and the World Weather Attribution project.

As discussed at this site in a recent Climate Explained post, the links between tornadoes and climate change are more nuanced than for phenomena such as heat waves or extreme rainfall. Among the 40-plus World Weather Attribution assessments and 150-plus Explaining Extreme Events papers to date, not a single one has tried to connect the odds of a particular tornado outbreak to climate change – surely in part because tornado data is so fragmented and because tornadoes are such rare, localized events.

It’s clear that the moist, record-warm air mass in place on December 10, assisted by record-warm temperatures for the time of year over the Gulf of Mexico, was essential for that day’s tornadoes. However, some of the other ingredients of high-end tornadic storms, such as a strong jet stream and strong vertical wind shear, do not necessarily intensify as the atmosphere warms (in fact, they’re often weaker during the hottest times of the year).

All this helps explain why there’s been no long-term observed trend in the frequency of the most violent tornadoes. What scientists have found is growing variability – twisters clustered into larger outbreaks, with longer quiet periods in between – and also a multi-decadal shift in tornado-favorable environments from the Great Plains toward the Mississippi Valley and Mid-South.

Wednesday’s storm system might actually be a more tractable candidate for an attribution study than Friday’s tornado outbreak. For one thing, it was a larger-scale weather feature, something that’s more readily simulated within a regional or global computer model. Also, the sheer rarity of Wednesday’s varied weather features seems to be at least on par with the large-scale pattern of Friday’s tornado outbreak, perhaps even more exceptional (even though it wasn’t more destructive).

We’ll see if any attribution research groups take up this challenge.

Assessment of Friday’s tornado catastrophe continues to unfold

The NWS office in Paducah, KY, announced Wednesday that it had assigned a high-end EF4 rating on the Enhanced Fujita Scale to the portion of the path of Friday’s prolonged tornadic Quad-State Supercell that extended across the office’s service area. That swath was a continuous 128 miles of damage – itself astounding, and likely to be extended as adjacent offices complete their own surveys. Peak winds along this segment were estimated at 190 mph, just below the EF5 strength (over 200 mph).

The National Weather Service/Louisville office is evaluating the final 35 miles of the quad-state track, with initial estimates of at least EF3 damage, and the NWS/Memphis office is surveying the first part of the track. It remains possible that this full tornado path will approach the longest in U.S. history, a 219-mile-long swath produced by the Tri-State Tornado of March 18, 1925. More recent research estimated that the longest near-continuous segment of that tornado path may have been “only” 174 miles long.

Although some of the damage in Kentucky may have seemed at first glance to be EF5-level, such as foundations swept clean, the actual rating hinges on how well built a particular structure was and how tightly it was secured to its foundation. It’s also important to keep in mind that an entire tornado’s track is classified based on the most severe damage found, even if it was only to a tiny area. A twister with extensive EF4 damage can still be far more destructive overall than one with only a small amount of EF4/EF5 damage.

At least 88 deaths have been confirmed from Friday’s tornadoes. Most of those (74) have been in Kentucky, where more than 100 remained missing as of Wednesday. Friday’s toll is more than double that of the previous record for any December tornado day – the 38 people killed by an EF5 tornado that struck Vicksburg, Mississippi, on Dec. 5, 1953.

Friday was also the nation’s deadliest tornado day at any time of year since a catastrophic twister killed 158 people in and near Joplin, Missouri, on May 22, 2011.

There is no official estimate yet of the financial toll from this outbreak, though it seems virtually certain to rise well into the hundreds of millions and perhaps to more than $1 billion.

Jeff Masters, Maximiliano Herrera, and Christopher Burt contributed to this post.

Source link