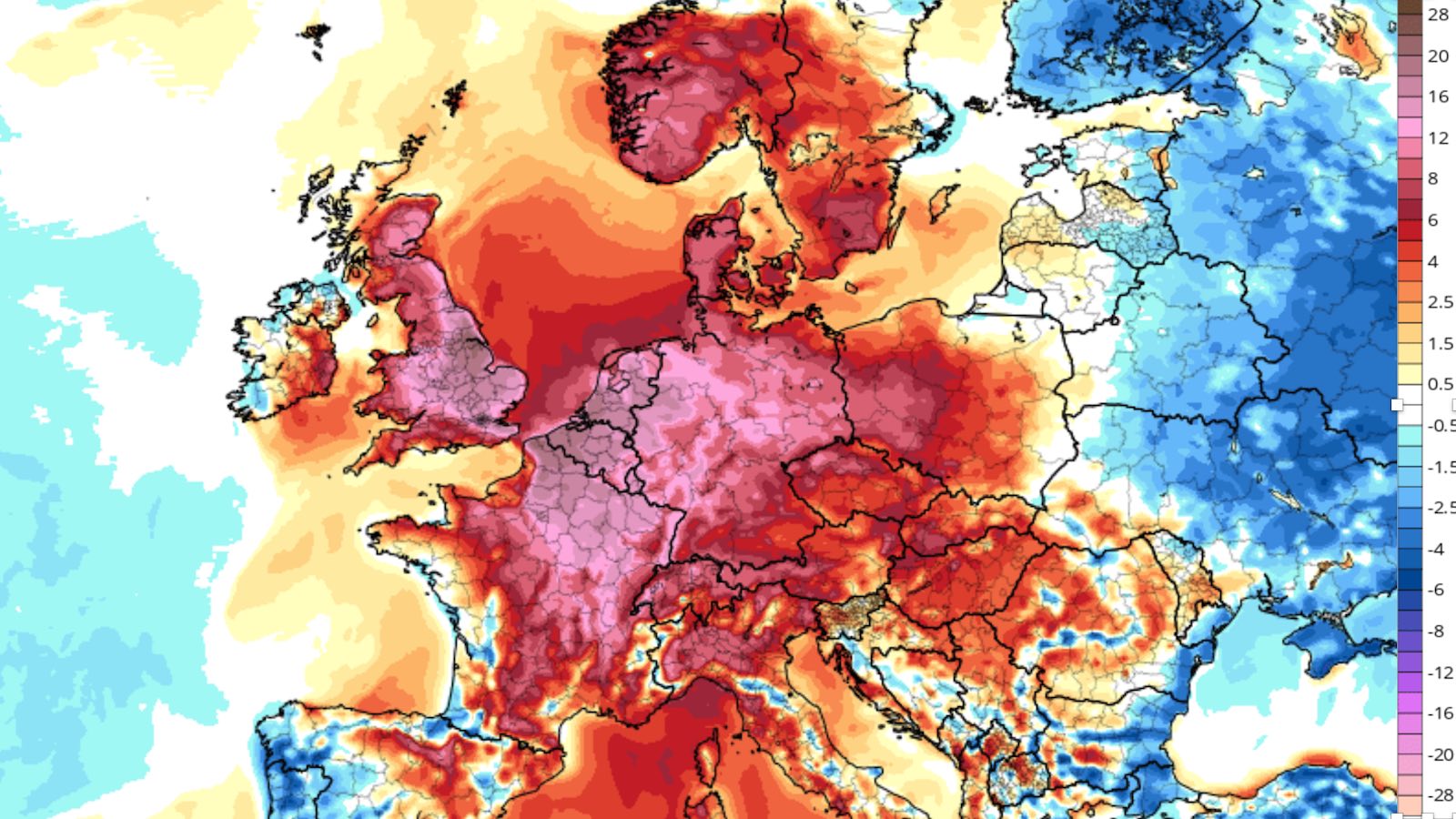

Dozens of all-time record highs melted on Monday and Tuesday under a searing, deadly European heat wave that has caused at least 1,169 heat-related deaths in Spain and Portugal. The heat wave has also brought the hottest day on record for many locations in France and the hottest temperatures — by far — ever observed in the United Kingdom.

The record-smashing heat in Europe’s normally mild, maritime northwest corner was eerily comparable to the astounding heat wave in the U.S. Pacific Northwest and far southwest Canada in June 2022. The latter was found to have been “virtually impossible” without human-produced climate change.

By 9 a.m. GMT on Tuesday, July 19, London’s Heathrow Airport had already surged past 90°F, and at 12:50 p.m., the airport’s official observing site for London recorded what, if confirmed, would be the hottest temperature in London history: 40.2 degrees Celsius, or 104.4 degrees Fahrenheit.

Despite accusations that the concrete jungle of Heathrow, which has been in place for decades, had artificially boosted the temperature, many other observing sites across the U.K. also set preliminary all-time highs on Tuesday. Dozens topped the previous national record.

The hottest as of this writing, and a new record for the United Kingdom if confirmed, is 40.3°C (104.5°F) in Coningsby, about 100 miles north of London and only about 10 miles from the North Sea coast.

As the heat wave loomed, the first “red extreme” warning ever issued by the UK Met Office prompted a partial shutdown of British society on Monday and Tuesday. Train schedules were reduced and many activities were canceled.

On Tuesday, multiple fires broke out across the city, creating surreal scenes in one of the world’s largest metropolitan areas.

All-time highs for Wales and Ireland

The town of Hawarden soared to 37.1°F (98.8°F) on Monday, setting an all-time record for Wales. Across the Irish Sea, Dublin experienced its highest temperature on record Monday with 33.1°C (91.6°F).

The only higher reading ever officially collected in Ireland was 33.3°C (91.9°F) at Kilkenny Castle on June 26, 1887. However, a paper now in press at the journal Climate of the Past, led by Katherine Dooley of National University of Ireland, Maynooth, finds multiple red flags with this supposed record, including an exposed measurement site that would not meet modern standards and a lack of supporting data nearby. If the 1887 reading is discounted, then the Dublin reading of July 18, 2022, becomes the hottest reliable temperature ever observed in Ireland.

Computer models had correctly flagged the potential for truly extreme heat in northwest Europe for days on end. Some of the models, particularly the American GFS model, were overheated — largely because of long-established summer biases in surface temperatures. Yet even if the GFS’s much-publicized forecast of a UK peak of 43 degrees Celsius (109.4 degrees Fahrenheit) failed to materialize, the eye-popping model output did alert forecasters, emergency managers, and the public that some truly unprecedented conditions were possible.

In the end, the UK Met Office’s public forecasts on Sunday of unprecedented peak highs close to 40°C (104°F) on Tuesday were both attention-grabbing and remarkably accurate.

Blazes rage and records tumble across the far western Continent

The northward surge of records heat reached France, Spain, and Portugal several days ahead of the UK. More than 100 stations in France set all-time highs on Monday.

“I don’t have the words tonight even though we’ve been expecting it a long time,” tweeted meteorologist Fabien Delacour, who catalogued the many stations that saw unprecedented heat.

Arguably the most remarkable of these was in Brest, just a couple of miles from the far northwest corner of France on the water-surrounded Brittany Peninsula. Brest’s all-time record Monday of 39.3°C (102.7°F) smashed the previous all-time high of 35.2°C (95.4°F) by more than 7°F — a phenomenal margin for a longstanding weather station — and far outstripped the average daily high in mid-July of 20.7°C (69.3°F). Only a few days in Brest have ever topped 90°F, much less 100°F.

Combined with scant rainfall, the July heat has led to widespread wildfires across western France, western Spain, and Portugal.

Eucalyptus forests — native to Australia, but widely planted across parts of Iberia over the past 50 years despite their exceptional fire risk — are one factor in the fire hazard along with the record heat and intense drought.

This week in climate leadership

At a time when geopolitical crises such as inflation and the Ukraine war have pulled attention away from tackling heat-trapping greenhouse emissions, two developments this week are worth noting:

Moving toward COP 27: The Petersburg Climate Dialogue took place in Berlin between July 17 and 19. This UN-sponsored meeting of representatives from 40 countries aimed to highlight the need for action on the “loss and damage” provisions of the Paris agreement and to help pave the way for the next United Nations COP meeting, scheduled for November 7-18 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt.

“No nation is immune” from a human-warmed climate, warned UN secretary general Antonio Guierres, “yet we continue to feed our fossil fuel addiction.” The leader of the 2021 COP meeting in Glasgow, Britian’s Alok Sharma, said: “As this meeting is taking place, parts of Europe are baking, indeed they’re burning … please, let’s speed up our work.”

U.S. climate emergency? With relentless heat baking much of the United States, the Washington Post reported that U.S. president Joe Biden may declare a national climate emergency as soon as Wednesday.

As of July 2022, 23 national governments and a total of 2,247 jurisdictions in 39 countries — together representing a billion people — had issued such declarations. The Climate Emergency Act of 2021 was introduced in the House by Rep. Earl Blumenthal (D-Oregon) but failed to gain traction.

Major climate action has been gridlocked for months in Congress. A climate emergency declaration would give Biden a chance to highlight the issue while heat waves are scorching much of the Northern Hemisphere. Declaring a national emergency can allow the U.S. president to invoke as many as 123 statutory powers, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Such a declaration would also allow Biden to show alignment with other nations and world leaders without requiring congressional approval.

Also see: Heat waves and climate change: Is there a connection? and How to stay cool in hot weather

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.

Website visitors can comment on “Eye on the Storm” posts (see comments policy below). Sign up to receive notices of new postings here.

Source link